Name one public official in Los Angeles. Did you come up with Eric Garcetti? Good. He’s the mayor of the second largest city in the U.S., and has elevated his public profile on the national stage by courting a presidential bid (when his city needed him more) and securing L.A. as the host city for the 2028 Olympics (a flashy decision that could exacerbate our homeless problem). You should know his name.

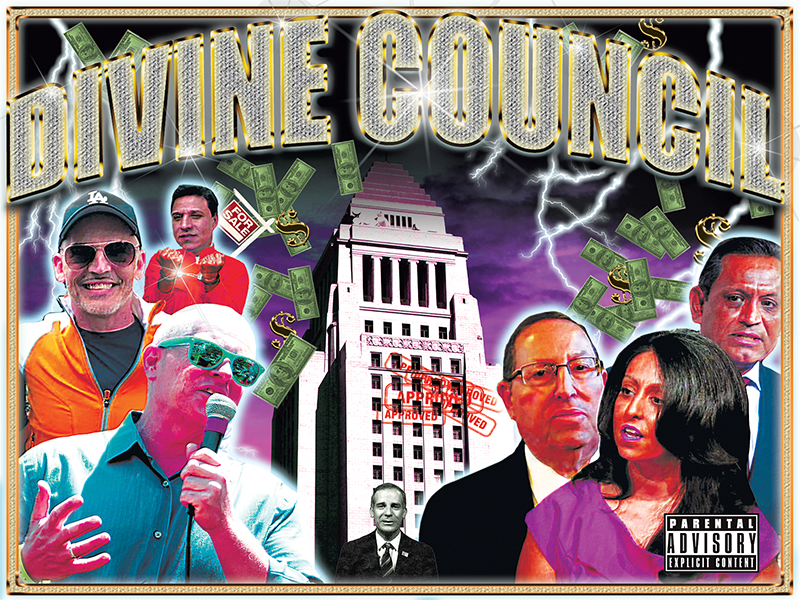

But the mayoral office in the city of Los Angeles is notoriously weak. If you care about the future of this city teetering on the edge of becoming one that only the wealthy can afford, you would be better served knowing who represents you on the 15-member City Council. And, if you live in one of two City Council districts in a run-off in November, you might not cast a more important vote this election.

Think of the mayor as more of a figurehead. Most decisions, especially ones that impact communities and renters, like whether to help tenants pay their rent during a deadly pandemic and economic crisis, are actually made by the City Council. The mayor proposes a budget every year, but it’s the City Council that listens to public demands and votes on the numbers. When Garcetti announced in June that he would trim $150 million from the $3.1 billion LAPD budget — barely offsetting the $120 million budget increase he had granted the police department before protests against police brutality stretched across L.A. — he did so with the support of City Council president Nury Martinez. It was ultimately up to the City Council to redirect the money.

That’s not to say that Garcetti does not have any unilateral power or sway. The mayoral office comes with executive powers, and a stronger leader than Garcetti could set a policy agenda for the council to follow (likening him to a floppy noodle, some haters call him “Spaghetti Garcetti”).

That power dynamic played out last spring when Garcetti declared that cleanups of homeless encampments would be focused on providing services and humanitarian aid, not the enforcement of city laws that restrict where people can sleep and the size of belongings they can keep with them. It was an important shift. Outreach crews had said the enforcement approach made it difficult to build the trust that’s often needed to get unhoused residents into safe shelter and permanent housing; social workers said they were often viewed as bad guys intent on tossing out belongings like medical paperwork and tents.

Garcetti’s new tack lasted about a month. Martinez and several other City Councilmembers, including Paul Krekorian, Paul Koretz, and Mitch O’Farrell, complained that trash and things were piling up and blocking sidewalks (the city has provided very few trash cans in public areas where unhoused residents post up), and ordered the city’s sanitation department to prioritize enforcement again. Councilmembers can refuse to build or force to fruition shelters and low-income apartments for the city’s homeless residents, a population that largely due to high housing costs, low wages, and a severe shortage of subsidized apartments now totals at least 41,290 within the city’s borders alone.

Most scarily, the power of City Councilmembers often goes unchecked, especially when it comes to what gets built in our neighborhoods. An individual councilmember decides whether to approve a development project (it’s almost always a “yes”), and the rest of the council falls in line. Not every development project requires City Council approval. But some of the biggest and most impactful do, and the votes are almost always unanimous. The redevelopment and expansion of Hollywood’s charming Crossroads of the World? Unanimous. NoHo West, the North Hollywood development equated to a mini city? Unanimous. Oceanwide Plaza, the megacomplex of Downtown L.A. skyscrapers with 504 condos and a 700-foot digital billboard? Unanimous. The 30-story tower called “Cumulus” that brought 1,210 apartments to West Adams? Unanimous. College Station, the 725 market-rate apartments that many Chinatown residents opposed? Unanimous.

The unwritten rule that councilmembers don’t object to what another wants in his district is understandable: Each councilmember represents, on average, 258,956 residents — a population equivalent to New York’s second largest city — and the districts are disparate from one another. Mike Bonin has Pacific Palisades and Venice. Gilbert Cedillo has Westlake and Chinatown. Each Councilmember is trusted to know what’s best for his or her communities. But the practice is also dangerous.

No one on City Council dissented when former Los Angeles City Councilmember Jose Huizar, who represented Downtown L.A. — a neighborhood reshaped over his 15-year tenure by new skyscrapers filled with expensive hotels, condos, and restaurants — moved two development projects through the City Council that have since been linked to a sweeping federal corruption probe at City Hall. One of those projects was a 35-story tower with 475 apartments in the Arts District. The apartments would be mostly market-rate, catering to tenants who can afford rents of about $2,764, or the going price in the neighborhood (compared to the citywide average of $2,018, according to figures from real estate data tracker CoStar).

In connection with the FBI probe, Huizar was accused of seeking out and accepting more than $1.4 million in bribes from developers and charged in June with one count of felony racketeering. In court records, the Arts District development is referred to only as “Project M,” but key details point to it being a project developed by Carmel Partners at 520 Mateo, next to Bavel and Zinc Cafe. (Carmel also developed the Cumulus tower in West Adams).

An affidavit filed by an FBI investigator, who reviewed e-mails and texts and “intercepted wire and electronic communications,” imply Carmel’s plans might never have been approved if Huizar had not intervened.

Two years ago, the councilmember allegedly put pressure on the city’s planning department to sign off on a general plan amendment that it had initially rejected and that was needed for the plans to advance. As the then-chair of the council’s Planning and Land Use Management Committee, Huizar also supported Carmel when it wanted to significantly increase the height of its proposed tower, from 13 stories to 35, and reduce by two dozen the number of apartments it would set aside for low-income tenants. With Huizar’s blessing, those plans advanced on October 31, 2018 to the full City Council, where they were approved on a vote of 14 to 0.

According to the FBI affidavit, an executive with the development company bragged about the project approval in an email to employees: “Our obligations related to rent restrictions and union involvement are minimal compared to other future projects in the area … the entitlement of the tallest building in the arts district by 3 times (35 stories) in a wealthy opinionated hipster community [is] truly amazing.”

Why did Huizar do it? Federal prosecutors allege that in exchange for his support, the councilmember solicited $75,000 in donations for an unnamed relative’s election campaign. That relative is widely known to be his wife Richelle, who launched a bid in September 2018 to replace the termed-out City Council member. Richelle Huizar quit her campaign two months later, after the FBI raided their Boyle Heights home. Until his arrest and suspension from the council on June 23, Huizar, who now faces a felony racketeering charge, exercised singular control over a project in an area starved for affordable housing.

So if you care about the future of L.A., talk to your City Councilmember. They have more sway than you know. But so do you. Don’t like the way things are going in your neighborhood? Vote them out.

theLAnd Voter Guide

- Immigrant Activists Have Given Me More Hope Than the Democratic Party

- The Progressive Challenger Who Wants to Unseat a Democratic Titan

- Endorsing the Lesser of Two Evils in this Stupid, Sad, and Fake Election

- A Conversation With Kendrick Sampson on Activism and Police Abolition

- Jackie Lacey Vs. The People

- The L.A. Politicians With More Power Than the Mayor

- A Battle for the Soul of California: An Oral History of Prop 15

- Godfrey Santos Plata Wants to Stand Up to Your Landlord

- Fatima Iqbal-Zubair is the Antidote to 2020 Pessimism

- Holly Mitchell is Ready to Take on Los Angeles

- Is George Gascon Really the Godfather of Progressive Prosecutors?

- L.A. Progressive Voter Guide

- Nithya Raman, the Progressive Candidate Running for City Council