The first elementary school Godfrey Santos Plata attended in Los Angeles was in a predominantly Black community. It was 1990 and he and his parents had immigrated to the United States from the Philippines two years earlier. His parents, who he says had been socialized to buy into anti-Black stereotypes, used coded language to describe his school. “They would say things like ‘Be careful who you hang around’ or ‘Don’t listen to everyone you meet,’” Plata says.

He was born in the Philippines during the last few years of the regime of Ferdinand Marcos, one of the most notorious dictators in the world. His father, whose friends were murdered for their political beliefs, discouraged Plata from getting involved in politics, even after they moved to the United States. “I remember my dad sat down with my sister and me, because they saw the types of questions we would start asking, and [he’d be] saying, ‘We’re a conservative family,’” Plata says. What he meant was that they were in the United States to keep their head down and work toward the American Dream.

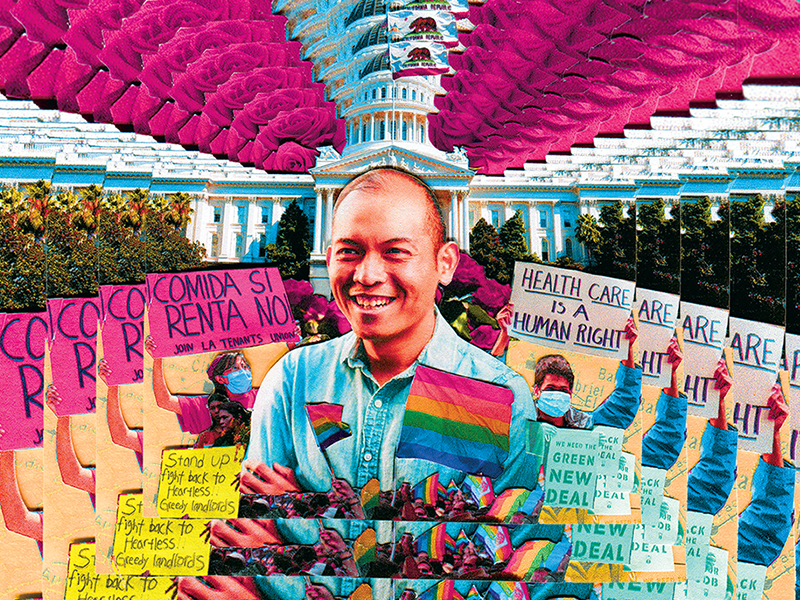

Yet growing up in a poor immigrant family during a volatile era in L.A. — he witnessed the 1992 L.A. Uprising when he was eight — was what motivated Plata to not only venture into politics, but also to dedicate his life to achieving racial justice. As the challenger to three-term incumbent Miguel Santiago in California State Assembly’s 53rd District seat, Plata is focused on reaching working class communities of color in his district. He champions progressive policies such as defunding the police, Health Care For All, a California Green New Deal, and guaranteeing a tenant’s right to counsel. Policies like these are ones that his opponent has a mixed record on, possibly because of his reliance on donations from police and landlord unions and other special interests. (Plata pledged not to take donations from real estate interests or police unions; Santiago did not respond to requests for comment.)

If elected in November, Plata would achieve many firsts for the State Assembly. According to his campaign, he would be the first out queer immigrant in the Assembly and the first Filipino to represent Greater LA there. Perhaps more significantly, he would also be the only renter on the Assembly.

There are roughly half a million people living in the 53rd Assembly District, which encompasses diverse L.A. neighborhoods like Koreatown, Westlake, and Boyle Heights, as well as the cities of Vernon and Huntington Park. The district has low voter turnout: Two years ago, Plata’s opponent, Santiago, was reelected with only 57,388 votes, around 30% of the registered voters in the district. (Santiago has won anywhere from 58 to 70% of the vote during the last two general elections, which means Plata’s odds of winning are slim, but not impossible.)

For now, he’s willing to celebrate the small victories — like winning 37% of the vote in the March 3 primary, as Santiago’s only challenger. “That’s 37% of the district that I live in … [and that] many of you live in, that’s actually saying, ‘Hey, I know you’ve been in that seat, but we actually need a different way,’” he says during his 36th birthday party in late August, which he’s turned into a campaign fundraiser on Zoom.

He’s wearing a button down shirt and a bowtie and dances in his living room to pop and R&B hits spun by a DJ. A few days later, we reunite on Zoom for a formal interview. Both times, I find his enthusiasm for dismantling how things are usually done in Sacramento to be infectious. I also observe how personal these issues are to him and how they fuel his campaign.

For example, Plata says his rent on his Koreatown apartment is 40% of his salary (he is a director of regional leadership development at the nonprofit Leadership for Educational Equity, where he designs and facilitates workshops for teachers about organizing, advocacy, policy and electoral politics). Like many other renters in his district, he is cost-burdened, according to the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition: anyone who pays more than 30% of their salary on housing.

Plata knows from personal experience how life-changing it would be for tenants to have a legal right to counsel. When he was reading his current lease, he found a hidden page that would have waived his right to relocation fees should the landlord sell his building. When he protested to the management company, they said he was the first person to ever point that out, illustrating how landlords often have the upper hand in rental agreements. “That is the antithesis of what it means to live in a world in which housing is a human right,” Plata says.

READ MORE: The Rent Strike That Sparked a Movement

The state legislature sets the parameters for the policies that counties and cities can enact for the benefit of their residents. State laws like Costa Hawkins and the Ellis Act, both laws that Plata wants to repeal, respectively prevent cities from passing stronger rent control policies and allow landlords to legally evict tenants by shuttering their businesses. The problem is, state politicians are incentivized to reach out to wealthy voters and special interest groups, because of the dollars they contribute to campaigns. This might explain why the state legislature failed to pass major police reform bills, even after the momentum of this summer’s resurgent Black Lives Matter protests. This is also why the state passed legislation requiring tenants who can’t pay rent due to COVID-19 to pay 25% upfront to avoid an unlawful detainer; progressive advocates like Plata have long advocated for rent forgiveness.

Plata says that many families — who make less than minimum wage or who have lost their jobs or have had their hours cut — can’t afford to pay 25% of their rent upfront, even while receiving unemployment benefits. “The solutions we have come up with at the local and state levels both leave too much room for the possibility of an eviction wave that would be much more inhumane, let alone more expensive, than figuring out a cancellation or forgiveness program now in the immediate,” Plata says.

While Plata’s education platform is critical of charter schools for creating “competition with traditional public schools for students and funding,” according to his website, it’s hard to ignore what would seem to be a contradiction: His employer has ties to the charter school lobby and typically favors candidates that support them. Plata shakes off any suggestion of conflict, insisting that working at Leadership for Educational Equity has only hardened his conviction that the state should invest in public schools. “The diversity of perspectives I’ve been able to learn from definitely have helped me strengthen my own stances, analysis, and convictions, which you see represented on my policy platform and website,” he says.

For Plata, running for office is bigger than himself, and he understands that not all of his policies are going to make everyone happy. “For me this is about a power grab, honestly, for folks who are not getting [a seat] at the table,” he says. “I’ve learned that as a queer person, as a Filipino person, a person of color, an immigrant, I am going to take sides… For us to achieve justice, you have to take sides.”

theLAnd Voter Guide

- Immigrant Activists Have Given Me More Hope Than the Democratic Party

- The Progressive Challenger Who Wants to Unseat a Democratic Titan

- Endorsing the Lesser of Two Evils in this Stupid, Sad, and Fake Election

- A Conversation With Kendrick Sampson on Activism and Police Abolition

- Jackie Lacey Vs. The People

- The L.A. Politicians With More Power Than the Mayor

- A Battle for the Soul of California: An Oral History of Prop 15

- Godfrey Santos Plata Wants to Stand Up to Your Landlord

- Fatima Iqbal-Zubair is the Antidote to 2020 Pessimism

- Holly Mitchell is Ready to Take on Los Angeles

- Is George Gascon Really the Godfather of Progressive Prosecutors?

- L.A. Progressive Voter Guide

- Nithya Raman, the Progressive Candidate Running for City Council