In 2008, Holly Mitchell went to Sacramento to lobby the State Legislature. By the time she got home, she had decided she was going to join it. As the then-CEO of the nonprofit Crystal Stairs, one of the largest child development agencies in the state, she knew that a $1 billion cut from subsidized child care in California would wreak havoc on the lives of the working families she served — many of them bus drivers and T.S.A agents in South L.A.

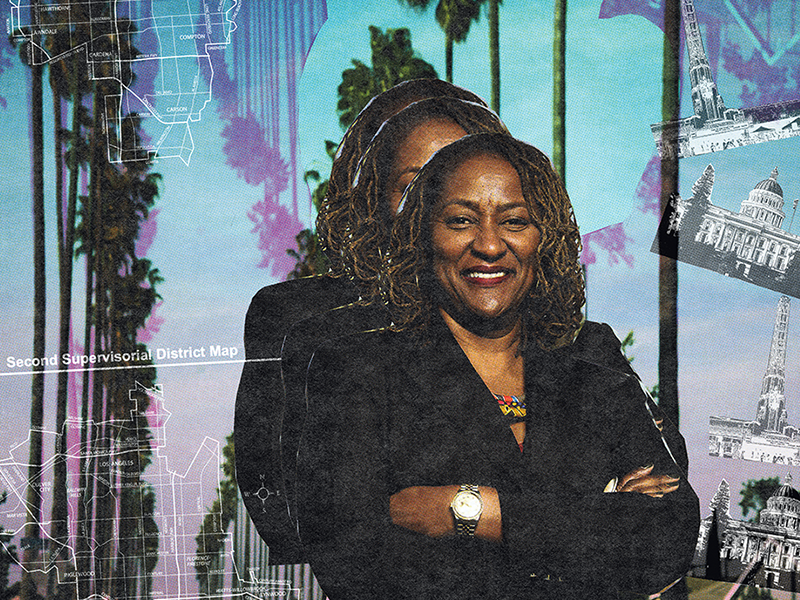

“I sat there and watched the legislature affect that cut and thought, ‘Well, this is B.S., and I can’t look to anybody else to save us. I’m gonna have to run it myself,’” says Mitchell, who wears red lipstick, gold hoop earrings, and chunky, stylish glasses that do little to hide the expressiveness of her eyes. “So I got mad and ran for office in 2010.”

Mitchell was elected that year to the State Assembly representing California’s 54th District, which includes her childhood neighborhood of Leimert Park. The state was suffering from a deep recession, and instead of watching helplessly as lawmakers pinched pennies at the expense of those who needed them most, she now had to vote for cuts herself, enduring what she calls “horrifically painful hearings” as chair of the budget committee for Health and Human Services.

The challenges didn’t discourage her. In 2013, she was elected to the State Senate, representing nearly 1 million people in District 30, which runs through the heart of South L.A. Three years later, she became Chair of the Senate’s Budget and Fiscal Review Committee, where she plays a major role in deciding how $215 billion are spent annually — on everything from healthcare and housing to education and transportation — in the nation’s most populous state.

So, where does one of California’s most influential politicians want to go next? Congress might seem like an obvious choice, but Mitchell, a third-generation Angeleno, has no intention of leaving her hometown. And with good reason: If she wins her race to fill the Second District seat on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, she will govern close to 2 million people — roughly triple the size of many Congressional districts in Southern California. With just five officials elected to serve roughly 10 million people across L.A. County, the Board of Supervisors is, in fact, one of the most powerful elected bodies in the country. Mitchell is competing for the Second District Seat — soon to be vacated by out-termed Supervisor Mark Ridley-Thomas — against Herb Wesson, the outgoing City Council member serving Central and South L.A. (Ridley-Thomas is now campaigning to take Wesson’s former seat.)

To Mitchell, 56, the differences between her and Wesson, 68, are vast: “It’s generational, it’s the kind of legislators we are, the kind of policy we do,” she says. “I’ve gone the deep policy route, budget route, and he’s gone the leadership route, and those are two very different tracts, in all honesty.”

Mitchell is quick to point out that two ex-City Council members, Jose Huizar and Mitch Englander, were charged in connection with a federal corruption investigation under Wesson’s watch as President of the City Council. “He fashions himself a dealmaker,” she says. “He’s got some, whether he chooses to acknowledge it or not, some serious baggage that he’s got to acknowledge and speak to.”

While Wesson has more recently come out in support of Black Lives Matter and its push to slash the LAPD’s budget and reimagine public safety, it represents a significant pivot from his 15 years in City Council. “His historic support of law enforcement, his endorsement by police unions, his crafting of Measure C several years ago, which rolled back police accountability gains that we had earned since the Rodney King experience, kind of flies in the face of what people are asking for now,” says Mitchell. “What I am proud of as a candidate is that I have not had to pivot. I am continuing to talk about the kind of work that I have done for ten years as an elected leader.” (Wesson, through his campaign, did not return repeated requests for comment.)

Her legislative record has earned her the respect of progressive activists like Eunisses Hernandez, who worked with Mitchell at the Women’s Policy Institute and now serves as the co-executive director of La Defensa and co-chair of the Re-Imagine L.A. campaign. “I’ve never met a legislator who was more open to talking than her at any level of government, and I’ve worked at every level,” says Hernandez. “If people want someone that represents them, that’s going to listen to them, hear them out — not just talk with you, but listen to you when you’re talking, she has a history of that. She has a history of not compromising in a way that’s detrimental to our folks.”

Plus, if Mitchell wins her race, it would create another change L.A. County has yet to see: An all-female Board of Supervisors. “Given all the years that L.A. County had an all-male board, give us a try,” she says. “I don’t think we can do any worse.”

Order theLAnd’s 2020 election zine here.

Mitchell splits her time between Sacramento, where she raised her 20-year-old son, and L.A.’s Midtown, where she calls home. She is an adoptive single parent, which she says she shares only “in the context of really understanding that I didn’t have an ex-husband, a baby daddy, anybody to support [me], it was just me.” She has never been married, but says she’s “still looking, so if you know of anyone” she is open to it. She has long caramel-colored locs — last year, she authored legislation to ban discrimination based on natural hair and protective hairstyles — and points to her graying roots as evidence of the quarantine.

Her days lately have been filled with all the duties of a state legislator, plus those of a candidate in the throes of a highly competitive campaign. Many of her evenings are spent participating in online panels, where her sign language skills — she worked at a school for the deaf in college — come in handy, usually as a means of thanking or acknowledging another speaker when they’re talking.

Mitchell grew up not far from here, in a household where heated policy debates were common. She remembers her parents, both social workers who met while employed by Child Protective Services, arguing over the death penalty (her father was for it, her mother was against it) at the dinner table. They divorced when Mitchell was six. Her mother went on to a career in probations and corrections, and her father took a job at the Los Angeles Urban League, and later, the state’s Division of Apprenticeship Standards.

“I saw my parents working in a space where, you know, my mother wrote a grant and helped start a program where some of her caseload women were hired by the county,” Mitchell says. “I think what that taught me was that government has an important role to play. Government can be innovative and creative and resourceful and leverage its power and resources for the greater good.”

Mitchell’s mother remarried and the family moved to Riverside when she was in high school. Prop 13, the ballot measure that decreased property taxes and resulted in huge cuts to public services, had recently passed and Mitchell noticed dramatic changes in her neighborhood as a result. The library had shorter hours and the lights at the city parks flickered off. It was the first time she began to experience the effects of the government contracting. (Proposition 15, which would amend the California State Constitution to close the tax loophole established by Prop 13, is on the ballot in November.)

Mitchell graduated from the University of California-Riverside with a degree in political science and later went to work for Senator Diane Watson as a consultant to the Senate Health Human Services Committee. She was always interested in how policy got made, but it wasn’t until that day in the childcare budget hearing in Sacramento that she decided to run for office. “I can’t sit on the sidelines and come to these hearings and shake my finger at other people,” she remembers thinking. “I need to go inside and effect the change that I know my community needs.”

Which is exactly what Mitchell did, having passed nearly 70 bills in the State Legislature, many of them aimed at protecting poor people, low-income renters, and working-class families. After meticulously working to manage the state budget in lean times, she helped create a multi-billion-dollar rainy day fund for entitlement programs like Medi-Cal and Denti-Cal. “When the economy is struggling, that’s when people require those government services and intervention the most,” says Mitchell. “That shouldn’t be the time we contract those services. That’s the time we should be expanding access to services, when people need it.”

If elected, Mitchell would enter the Board of Supervisors during a time of unprecedented transformation: In the last year, it has voted to consider restructuring the county and city’s homeless services agency, to stop expanding men’s and women’s central jails, and to put a measure on the ballot that would divert at least 10% of the general budget from jails and policing to social and community services. And in September, two of its five members called on Sheriff Villanueva to resign.

Mitchell acknowledges that the sheriff’s department, which has clashed openly with the Board of Supervisors for failing to comply with its Citizen Oversight Committee, has “a lot of history of inappropriate behavior” (an understatement). She believes the county needs to reverse a system where police have been turned into social workers, mental health professionals, drug counselors, transportation workers, and housing experts. “When public education fails, criminal justice is the backstop,” says Mitchell. Instead, “We have to fund services for people who need help.”

When she talks about her own relationship to law enforcement, Mitchell slows down and chooses her words carefully. “I know people are in pain, and we, because I will include myself in this statement, are tired” — she pauses here, emphasizing her own exhaustion — “Of being afraid for our sons and the men in our life. We are tired of the lack of accountability. There is a fatigue that I carry as a black woman that is indescribable,” she says. “I can remember my grandmothers talk about being weary and [thinking] what does that mean? I now know it. It’s a weariness. And I think we are seeing that explode all over the world.”

Homelessness is the other massive, increasingly unignorable issue the Board of Supervisors will need to contend with; it’s also one Mitchell has been working on for years, as a state Senator. After studying a pioneering model in Utah, she passed legislation to make California a housing-first state, which requires all state departments targeting homelessness to prioritize permanent supportive housing. And last year, a bill she authored made it illegal for landlords to discriminate against tenants who use Section 8 vouchers. “It can’t be a one-shot strategy,” she says, adding that the county’s approach has been far too narrowly focused. “Yes, we have to build, but I think we have to be creative in what we build. I think we have to look at modular units, we have to look at motel conversions.”

To Mitchell, the Board of Supervisors has a rare, real opportunity to make course corrections — and she is eager to be a part of its transformation. “We can’t look at this as a moment, this has to be perceived as a movement and a true transition in how we live and govern and exist,” she says, adding that government has to keep its foot on the accelerator even when public pressure dies down. “We have to really invest in the long run. And that’s what I’m committed to doing.”

theLAnd Voter Guide

- Immigrant Activists Have Given Me More Hope Than the Democratic Party

- The Progressive Challenger Who Wants to Unseat a Democratic Titan

- Endorsing the Lesser of Two Evils in this Stupid, Sad, and Fake Election

- A Conversation With Kendrick Sampson on Activism and Police Abolition

- Jackie Lacey Vs. The People

- The L.A. Politicians With More Power Than the Mayor

- A Battle for the Soul of California: An Oral History of Prop 15

- Godfrey Santos Plata Wants to Stand Up to Your Landlord

- Fatima Iqbal-Zubair is the Antidote to 2020 Pessimism

- Holly Mitchell is Ready to Take on Los Angeles

- Is George Gascon Really the Godfather of Progressive Prosecutors?

- L.A. Progressive Voter Guide

- Nithya Raman, the Progressive Candidate Running for City Council