L.A. has long deceived itself with the notion of its own immunity.

A liberal sanctuary, an island on the land, the great exception within the context of American exceptionalism. But Covid-19 exposed the extent of the infection that has been festering all along. For all our self-sustaining myths, you can’t ignore 66,000 unhoused, huddled on every other corner throughout the county. A criminal justice system plagued with scandal, as swift to demonize Black and Brown people as anywhere in the Deep South. For all the leftist platitudes of the political class, their hand-in-glove redevelopment schemes and six-figure donations from cop unions and condo builders tell a different story. This is original sin.

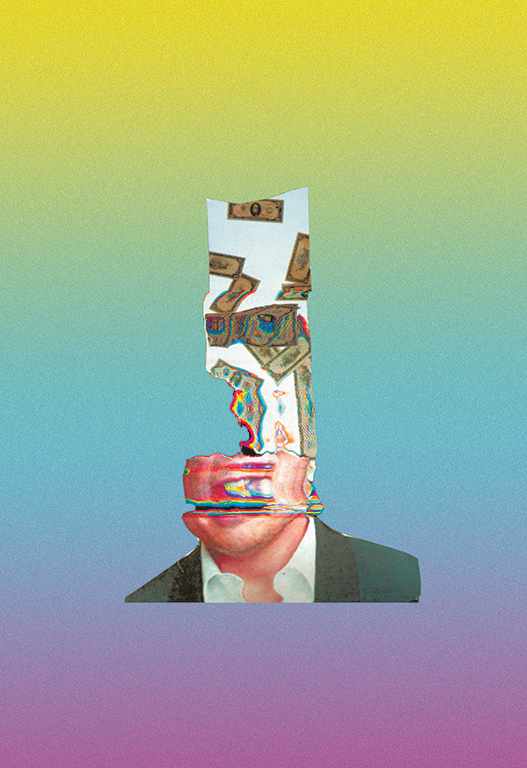

In the economic boom of the late 19th Century, the bad joke was that the word “real” in Los Angeles was synonymous with “real estate.” Forget Chinatown — freshly arrested L.A. City Councilmen Jose Huizar and Mitch Englander are likely heading to federal prison for accepting red envelopes filled with cash from Chinese developers. It has been the strength and weakness of the Angeleno to betray a blinkered optimism. This is an end-of-the-Earth chimera that conjured itself into existence: Angelyne and Dennis Woodruff; Jack Parsons and Father Yod; Thomas Mapother IV and Earvin Johnson Jr. Sunshine myth and vexed noir baked into the equation. The land that birthed “Fuck the Police” but also Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright.” For a city so fundamentally invested in plasticine reinvention, we have to instinctively believe that things can improve.

These last several months have forced us to confront the crimes of our past, while also battling multiple crises in our present, secure in the understanding that if we don’t figure out a plan for the future, there won’t be one worth inhabiting. A homeless epidemic met a medical one, and thousands have died in L.A. County alone. Strip mall pupusa vendors and Michelin-starred restaurants, dive bars and used bookstores, D.I.Y. venues and members-only social clubs have already been wiped out, never to return. Everyone has been negatively affected, save for the billionaires whose wealth has multiplied so exponentially that it makes you want to spend your quarantine building a guillotine.

L.A.’s unemployment rate hasn’t been this high since the Great Depression, when Pasadena spent $20,000 a year on guards to stop people from jumping off the “Suicide Bridge.” Hollywood would probably remake The Fall of the Roman Empire right now if anyone were allowed to film. But despite the freefall, some are determined to reimagine what L.A. can be if it corrects for its errors, invests the city’s still-immense wealth back into the people, and attempts to actually build it into the progressive utopia that it pretends to be. These are the state, local, and county politicians and grassroots activists fighting for humane and thoughtful solutions to the problems of homelessness, housing, structural racism, and more. Those who would make L.A. a better place to actually live, and not just the kind of place even Biggie confessed was great to visit.

To understand L.A.’s homeless problem is to confront the scarcity of affordable housing, the historical ramifications of redlining and institutional racism, the breakdown in mental health, the criminalization of the unhoused, and the political inertia that extends from Spring Street to Sacramento to Washington, D.C. It’s a Gordian knot that encompasses multiple failures in public policy, civic planning, and our evangelical belief in the private sector. There are no easy answers, but it’s hard to imagine doing much worse.

According to the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, there are 66,436 people experiencing homelessness throughout the county. Despite the 2016 passage of Proposition HHH — a $1.2 billion bond aimed at funding the construction of permanent-supportive housing — the city is still far from its goal of creating 10,000 new units in a decade. In the meantime, the rate of homelessness has exploded, rising nearly 13 percent from last year. With more than half the county out of work and a statewide eviction moratorium scheduled to lapse at the end of September, as many as 120,000 more households could soon become homeless, according to a recent UCLA study.

A U.N. worker infamously compared Skid Row to a Syrian refugee camp, but there was at least a civil war to explain the devastation in that country. South of Main exists on an alien scale of human suffering, a hallucinatory nightmare somewhere between Bosch and Night of the Living Dead, and somehow, still just a few blocks away from zen hi-fi bars serving $7 lattes. It’s crushing to witness the thousands condemned to such squalor, but even more troubling to wonder about a future feudalistic L.A., where the number of unhoused grows exponentially, and the politicians fight over who gets to give a no-bid “Dump the Homeless on Mars” contract to X Æ A-Xii Musk IV.

But nevermind that bloodcurdling future, it’s the present that haunts Kevin de León, former president pro tempore of California State Senate. “I took some family relatives into Skid Row and they were all saying ‘no puede ser possible!’” says de León, who is expected to take office in December as City Councilperson for District 14, Huizar’s former district, which includes Skid Row. “In Spanish, one of them said, ‘This looks like the third world,’ to which another relative said, ‘That’s an insult to third world countries.'”

It’s deeply humiliating that a perceived forward-thinking progressive place, one of the richest cities in one of the wealthiest states in one of the richest nations, is still grappling with such a large concentration of unhoused individuals. This recent explosion is a dystopian nightmare unlike anything we’ve ever seen.

The downtown “revival” championed by Huizar and Garcetti — and the previous mayors Antonio Villaraigosa and Richard Riordan, the latter of whom conveniently owned multi-millions of DTLA real estate — came at a steep cost. The entire district became awash in real estate investment trusts, Ritz Carltons, and billionaires controlling war chests of dirty money, turning it into a schlocky Edison-bulbed tourist carnival that priced out almost anyone making under six figures. While plenty of other neighborhoods have had their own unhappy stories pertaining to gentrification, displacement, and being Sqirl’ed, the end pattern is always similar: the poor and working class are pushed further east or out of the city altogether, what’s left of the middle class struggles to make rent, and rows of tents line every freeway underpass and available scrap of sidewalk — until the cops do a sweep and start clearing out possessions and handing out tickets.

It’s partially the result of a byzantine process required to build new housing. More than three years after the passage of HHH, there have been only two completed housing projects (though there have been 15 temporary shelters built in the last two years through the “A Bridge Home” program). Since January, 57 planned supportive housing developments have fallen behind schedule, which is only somewhat due to the coronavirus. The Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles, which metes out the federal Section 8 subsidies, has begun to run out of rental vouchers to give to the developers. Many of the builders are non-profits, but without the government defraying costs, most claim they can’t secure private mortgages to finance the development.

“The current approach to homelessness simply isn’t working,” says de León, who authored the “No Place like Home” initiative in Sacramento, which was signed by Governor Jerry Brown. While it promised a $2 billion statewide investment for chronically homeless individuals with mental illness — including slightly under a billion earmarked for L.A. — the project has had its own share of bureaucratic headaches related to litigation and a delayed dispersal of funds. “We have to set hard deadlines for building emergency shelters and long term housing, and terminate wasteful contracts,” says de León. “We need to strongly consider focusing on the construction of pre-fab modular housing and the outright purchase of motels to house people. We can’t let the cumbersome nature of bureaucracy and the lengthy permitting process slow this down.”

De León says it’s imperative to set a firm cap on per-unit costs. Even though many of the builders are non-profits and allies to progressive causes, you’d think that Tony Soprano and Ralphie Cifaretto were behind the construction, with one Koreatown development spending $700,000 per apartment. But expediting the process and removing bureaucratic red tape is only one part of a difficult calculus. These aren’t integers, but human beings coping with their own traumas, and oftentimes mental illness or substance abuse addictions. While many share commonalities, a one-size-fits-all approach can’t fix such a complex issue.

“In Spanish, one of them said, ‘This looks like the third world,’ to which another relative said, ‘That’s an insult to third world countries.'”

Kevin de León, former president pro tempore of California State Senate

In Venice, Councilmember Mike Bonin has been a steadfast advocate for the unhoused, despite a vocal opposition among some of his constituency. In the days just before the pandemic began, Venice opened a 154-bed temporary shelter, which would theoretically cover less than 10 percent of the area’s population.

“I make the analogy that homelessness is like cancer in that there’s no one form of it,” Bonin says. “Each type of cancer has different manifestations and prognoses. Someone who is chronically homeless requires different treatment than someone recently homeless due to an abusive relationship, or a loss of a job, or a teen runaway. Age, race, and gender makes a difference, too.”

Black people make up over a third of the unhoused, despite comprising just eight percent of the county’s overall population. Locally, that’s partly the residual effect of structural racism: the housing covenants that stymied wealth-building, a legacy of rundown inner-city schools that never received the same investments as their white counterparts, barriers in employment, and a war on drugs that disproportionately targeted and incarcerated people of color.

“For good reason, we’ve focused most of our time and resources on housing the most vulnerable,” Bonin continues. “We, of course, want to focus on the people who might die. But now the numbers of unhoused are so big and the resources are so limited that we’re effectively telling people who are near-homeless that they’re not homeless enough to qualify for the solution. That’s like telling people newly diagnosed with cancer, come back when you’re stage four.”

The city recently advertised a lottery to help needy tenants in danger of eviction, but few see it as much more than a flawed stopgap (one based off 2019 income, which means practically nothing today). As for Project Roomkey, it was designed to usher 15,000 of the most vulnerable off the streets and into hotel rooms, but to date has only housed one quarter of that goal. The Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority’s latest quagmire is a proposal to spend $800 million (yes, a real number) to find available apartments across L.A. County and then subsidize the rent. But this is a tourniquet that involves finding landlords actually willing to rent to the homeless, and compounding that with the quixotic notion that at the end of 18 months, most of the dispossessed will somehow make enough money to afford full L.A. rent — something which few working people can afford in the first place. (The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in L.A. is $1,773, according to one estimate, or almost the entire monthly salary of a person working full-time at minimum wage.)

Solutions exist, but only if progressives successfully organize to run and elect politicians with courage, long-term foresight, and a stomach for endless courtroom battles. A more sage and lasting solution comes from UCLA’s Luskin Institute for Inequality and Democracy, which advocates exercising eminent domain on under-used tourist hotels. With commercial real estate flagging and brick-and-mortar on the decline, it’s also worth considering the city exercising eminent domain on long-vacant properties, fast-tracking a rezoning, and converting them into apartments.

But L.A. elected officials have historically only shown the desire to invoke eminent domain on aging pensioners on Bunker Hill and Mexican immigrants in Chavez Ravine. For over a century, this city has ceded decision-making to land barons, whether it was those buying up the San Fernando Valley in advance of the Owens Valley aqueduct, the mid-century cabals that used Communist fears to fend off public housing, or the latest private equity Zuul’s paving over paradise to put up 400 condo units with un-exorcised demons in the fridge next to the berry La Croix.

While the local plight is bleak, the November presidential election could offer some relief. Even though Joe “Crime Bill” Biden is no one’s idea of an acceptable candidate, he does represent the possibility of federal funds boosting depleted coffers at both the county and city level. Without it, there will be drastically reduced money for progressive projects, and the deaths of thousands of local small businesses — to say nothing of their workers. Hundreds of thousands of local jobs have evaporated in the wake of the pandemic. Even with a vaccine, which could take years to produce, a recovery will undoubtedly be slow and fitful.

In their dreary rhetorical manipulation, Tucker Carlson Republicans lie about how all these problems are the result of leftist governance. But the five-person L.A. County Board of Supervisors lacked a clear progressive majority until 2016, when both of its two Reaganite Republicans retired and one of the seats went to a Democrat. The neo-liberalist streak of L.A. mayors dates back to Tom Bradley, a fundamentally decent man and legendary figure, whose sympathies for the downtrodden were offset by close ties with downtown power brokers, Brentwood entertainment moguls, multi-national banks, and lupine developers. It’s the same “all business is good business” mentality that ushered in our current mayor, who has never understood the fundamental contradiction of being a progressive and making statements like “I never met a CEO I didn’t like.” Garcetti’s greatest achievement will be losing the battle for Amazon’s second headquarters.

One City Council candidate who has justifiably captured the local progressive imagination is Nithya Raman, a charismatic urban planner full of compelling ideas blessed with a policy wonk’s gift for budget crunching. Facing off against City Councilmember David Ryu in this November’s local election for District 4, Raman began in politics working for the City Administrative Officer in 2014. During her time there, she wrote a report outlining how over 85 percent of the city’s $100 million homelessness budget was squandered on jailing the homeless, rather than helping to procure permanent lodging.

“In L.A., we have people who speak the language of progressivism, but who don’t act with the urgency or integrity that this moment demands,” says Raman, who graduated from Harvard before receiving a master’s in urban planning from M.I.T. “We have some tenant protections in place, but we’ve never invested in the kind of infrastructure that helps tenants realize their rights: the right to counsel upon eviction, a landlord and tenant registry, and rent forgiveness during the pandemic — all while keeping smaller landlords from having to sell properties to the banks.”

“In L.A., we have people who speak the language of progressivism, but who don’t act with the urgency or integrity that this moment demands.”

Nithya Raman

Raman, a mother of two young twins and one of the founders of the local SELAH Neighborhood Homeless Coalition, has focused her campaign on housing and homelessness. For the latter, Raman, a former entertainment director of Time’s Up — an organization designed to combat sexual harassment in the entertainment industry — wants to build community access centers where outreach workers and mental health case workers will be anchored in specific neighborhoods. The idea is that they can get to know individuals by name and develop a level of trust to get them housing and support that can end their time on the streets.

“It’s become a labyrinthine process,” Raman says. “A neighborhood system allows people to be accountable; as it stands now, there’s no visibility of the process from the city electoral level. When you have people from the neighborhood with relationships to the unhoused, it presents real alternatives to calling 911 for every problem.”

But the homelessness crisis is merely the most inescapable aspect of a housing nightmare that shrouds L.A. Before the pandemic offered a brief cease-fire, the nihilistic forces of big capital had conspired to the point where even the gentrifiers were being gentrified. Neighborhoods like Silver Lake, Echo Park, and Highland Park are completely washed. If once defined by their diversity, character, and sabor, they’ve become post-hipster amusement parks with $70 an hour faux-retro bowling alleys and self-parodic, avian-themed, book-scarce bookstores, owned by alabaster refugees from the New York marketing world.

There are two perpetually warring contingents that make reasonable discussions of the housing crisis impossible: the NIMBYS (not in my backyard) and the YIMBYs (you can guess). The former are resolutely opposed to development of any kind; they tend to be white, senescent, and dedicated to the antiquated belief that Southern California will always be a homeowner’s paradise and if you work hard enough, everyone can buy a 3-bedroom, 2-bath in Valley Village — which is no longer actually affordable unless you’re a cast member on Vanderpump Rules. The YIMBY’s are usually well-meaning, but misguided in their belief that supply and demand solves everything. It’s clear that the free market system has spun out of control, or rather, that it’s succeeded in its most cynical and deregulated form to enrich the greediest caste.

READ MORE: The “Mayor of Skid Row” explains the intractable nature of the homelessness crisis

The National Association of Home Builders recently designated the L.A. region the least affordable housing market in the nation. In the fourth quarter of last year, just 11.3 percent of homes were affordable to families earning the area’s median income of $73,100. (In Los Angeles County itself, the median income is $64,251.) Rents might have dipped slightly over the last month or two, but the decline figures to be ephemeral. Most new developments include a token gesture of affordable priced units to ensure their projects get passed, but no matter how many units are built, rising rents far outstrip inflation.

“We need to hold elected officials to account, and I don’t think we should wait until they get indicted by the F.B.I.,” says Arielle Sallai, the housing & homelessness co-chair for the Democratic Socialists of America, Los Angeles. “We need to see community engagement in the process from the outset and question the very nature of how developments are approved and funded. The city needs to build real social housing. What vacant lots do the city, county, and state own that they’re doing nothing with? We need more militant actions because the traditional pathways aren’t working.”

Sallai saliently references the group of unhoused families that occupied some of the dozens of homes that Caltrans owned but abandoned when plans to extend the 710 Freeway fell through in 2018. Over the last four years, organizations like DSA L.A. and Ground Game L.A. have become some of the most impactful and respected political organizations of this generation not because millennials are petulant and spoiled Jacobin cosplayers, but rather, because they have galvanized those with the desire to redress the failures of snuff capitalism. For many under 40, there is the belief that the current system has betrayed them.

Even if outright socialism seems extreme to some, the reforms of the New Deal have been so ruthlessly dismantled over the last half-century that death has become the final safety net. Once upon a time, FDR was accused of being a Socialist, to which he perhaps apocryphally quipped that he was just trying to save capitalism. Either way, we’re witnessing the death rattle of Ronald Reagan’s intellectually bankrupt and Darwinian counter-revolution. The original California raisin’s shriveled cruelty started here, where he began to unravel the health care and public education system.

Reagan’s mellow lunacy sparked Howard Jarvis’s taxpayer revolt of 1978, which left state schools chronically underfunded by dramatically decreasing property taxes. A decade-and-a-half later, the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, enacted under Governor Pete “Prop 187” Wilson, stifled any meaningful ability for cities to control long-term rental values. For all the G.O.P. stereotypes of radical California, Republicans have occupied the Governor’s seat for 32 of the last 53 years.

One of the Sacramento legislators helping the state and city to crawl out from under the wreckage is venerable L.A. labor leader turned state Senator, Maria Elena Durazo:

“We’ve been focused on streamlining the process and taking the power out of the hands of local NIMBYs that refuse new housing construction,” says Durazo, who was elected to the California State Senate in 2018, representing an area that includes Central and East L.A. In 2019, Durazo sponsored Senate Bill 529, which sought to bar landlords from retaliatory evictions against tenants collectively organizing. It lost by one vote. This February, she introduced a bill enabling victims of violent crimes and their families to terminate a lease without penalty within six months of the crime having occurred.

“It’s not just a matter of pushing density. Some of the most overcrowded parts of the country are in my district,” Durazo says. “We need policies that build wealth and equity for those that actually live in those neighborhoods. Rents go up, values rise, but wages don’t. We need protections for renters. Two families are often forced to crowd into the same space. 50 new units is a good thing, but not if it only creates higher rents for the rest of the neighborhood.”

These aren’t the mom-and-pop landlords of decades’ past: all available land has been accounted for. Without serious action, private equity and real estate trusts will continue to gobble up every last square inch of the city. These are operations with zero stake or accountability to the community. Dead-eyed vultures with the aesthetic of a Scottsdale air conditioning contractor.

Take Taix, a once-beloved family-owned French restaurant and bar in Echo Park, which was sold for $12 million to something called The Holland Partner Group. The Vancouver, Washington-based behemoth is redeveloping the site into a hideous pigeon-gray 170 unit monstrosity — of which 93 percent will rent for market rate. There will be a zombified “new Taix,” but the deadening design sketch makes it look like an organic dog bakery. It’s the building equivalent of Goya’s “Saturn Devouring His Son,” a gentrified McUrbanism that will torment anyone who ever had a half-good memory over a whiskey soda and a French onion soup.

“The future will require creating more neighborhood institutions organized by and for the people,” Sallai says. “We need to force our elected officials to be responsive to the impacted groups, listen to their demands, and recognize their values.”

This cuts to the deeper question about L.A. It’s evident what its values were in the past, but unclear what they will be going forward. By its very essence, the home of Hollywood is filled with transplants who move here, spend years whining about the traffic and the lack of seasons, and vanish. It’s allowed for a political class to exploit those get-rich-quick desires and transient nature to create a city built for Instagram virality and Airbnbs — one that doesn’t cater to regular people working to survive.

This place will always be an alluring place to live, but immediate action needs to be taken to ensure that it’s actually inhabitable for teachers, firefighters, social workers, eloteros, bartenders, and artists. Our destiny for a chthonic divide between rich and poor is not preordained. The affordable housing success of Berlin, which in January instituted a five-year freeze on rent increases, reminds you that other ideas are possible and effective. We can set up land banks and consider a massive investment in public housing that refuses to rely on the price gouging private sector. We can attempt genuine urban land reform and green belts of the sort that were crushed before they ever had the chance. But it will not be enough to just have progressive politics; it will require vision, strength, and persistence. The soul of a city isn’t something you can rebuild.

The latest battle for the new Los Angeles began on May 30 at Pan-Pacific Park. Local Black Lives Matter organizers had long laid the groundwork in educating residents about the 600-plus deaths at the hands of law enforcement since District Attorney Jackie Lacey took office at the end of 2012. Over the last several years, BLM has put enough of a public spotlight on Lacey’s refusal to charge killer cops — staging weekly anti-Lacey protests in front of the Hall of Justice — that even the ex-Chief of Police requested that she prosecute. But to the average, self-consumed Angeleno, it hit differently to watch cops in riot gear firing tear gas projectiles at random protesters on that day in May, in front of organic markets that sell 17 kinds of shelf-stable infused bone broths. To see them taking batting practice with batons. To truly cement the reputation that L.A. law enforcement is famous for worldwide.

In the same way that Donald Trump’s election stunned sheltered white liberals, the revelation that the LAPD was still the LAPD came as a similar shock. For Black and Brown people, this was just another reminder of what they’d been saying all along. Did everyone think N.W.A., Cypress Hill, YG, and Kendrick Lamar were all making shit up? Melina Abdullah herself, one of the co-founders of BLM L.A., had been the target of a law enforcement plot that saddled her with eight trumped up misdemeanor charges connected to activism. (They were dismissed last February, shortly after theLAnd’s story on the charges.) But this has always been part of the great schism of L.A. life. The persecuted have long told anyone willing to listen about the corruption, brutality, racial profiling, and the school-to-prison pipeline, but politicians largely nodded their heads, issued vague proclamations, and offered a blank check to a series of opportunistic police chiefs and crooked sheriff’s.

Captured on video, the militarized goonery opened eyes that otherwise would’ve remained blind. The Black Lives Matters organizers deftly seized the moment with poignant calls for justice and shrewd budgetary analysis. The June L.A. City Council meeting in which they presented their proposed budget was as powerful as anything in recent memory. Unlike the bromides offered in the past, the City Council soon after voted to cut $150 million in LAPD funding. Most importantly, it took the first steps towards fundamentally reimagining the nature of local policing. After decades of accepting faulty inherited logic, a countervailing wisdom has emerged, reminding people that the police do not need to perform random traffic stops or serve as first responders to non-emergency 911 calls about mental health care, domestic unrest, and homelessness issues.

“The world has cracked open. I’ve never seen this level of openness to fundamental transformation. Watching the death of George Floyd made it clear that we weren’t crazy when we said that policing stems from slave catching. You could see it with your own eyes. It pierced the soul of the world,” Abdullah says, adding that BLM’s proposed budget is also about common sense. “Why would police respond to a mental health call or deal with 14-year old kids instead of a youth worker?…Why should they be doing traffic stops; if they see you with a broken taillight, they can just mail you a ticket. If they’d have done that, we’d still have Philando Castile and Sandra Bland with us.”

Abdullah mentions a Canadian program brought to her attention via Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, wherein police officers are replaced by service workers who offer to fix the taillight for drivers instead of ticketing them for it. The contrast clearly highlights how punitive and repressive the American mentality has become.

From the Zoot Suit Riots to the Rampart scandal, the history of L.A. policing is a series of rabid attacks on citizens they’re sworn to protect and serve. After 28 years of would-be reforms, the LAPD’s “elite” Metropolitan Division is currently under fire for an L.A. Times exposé revealing that they stopped Black motorists at a rate of more than five times that of their share in the city’s population. Not only that, but LAPD falsified so much information about alleged gang members that the state of California had to stop using it in their CalGang database. Chief Michel Moore came up through the ranks during the batterram era of Daryl Gates; his June quip at a press conference about the looters being as responsible for the death of George Floyd as the murderous police officers spoke volumes.

A pragmatism lies beyond the social justice imperative for defunding the police. Out of the nearly 18 million calls to the LAPD over the last decade, a Times report revealed that less than eight percent were for violent crimes. The majority were for traffic accidents and “minor disturbances.” In 2000, the LAPD total cost of operations was $1.2 billion; it has now ballooned to $3 billion-plus including overtime, and consumes over 50 percent of the city’s discretionary spending. As municipal revenues decline, it’s wise to slash bloated police budgets to divert non-emergency services towards trained professionals. The savings can be invested in housing, health care, anti-poverty programs, and education.

The underreported good news is that L.A. County’s violent crime rate is roughly one quarter of what is was in 1992. Despite a slight increase in the last two years, it remains near a 50-year low. While the police would love to take credit, there’s been a similar drop in many metropolitan areas. What’s glossed over is that the spikes of the ‘80s and ‘90s were heavily due to the ravages of the crack trade. Yet as the city has gotten safer, our style of policing, sentencing, and legal code remain racist and obsolete remnants of the tough-on-crime era. This is why many progressives have united against D.A. Lacey, who is up for reelection in November and whose campaign has been propped up by multiple police unions. During her tenure, her office has sent 22 people to death row — all people of color. Under her aegis, they have manipulated antiquated gang statutes and wielded gang enhancements to increase mass incarceration. To Abdullah, Lacey is inarguably the most corrupt and problematic D.A. in the country:

“When you look at the sheer volume of murders at the hands of the police, there’s nowhere else that even begins to rival L.A. County’s number. She’s an elected official who refuses to be held accountable,” says Abdullah. “There have been sexual misconduct cases in her department and in several instances, the victims have been transferred out, and the perpetrators were even advanced in their career. She has to go.”

This recalcitrance towards reform has left some on the left to conclude that police abolition is the only meaningful solution. That doesn’t mean a lack of community safety, but rather, it reflects the need for new organizations conducive to 21st Century values and basic human rights. After all, these are historically corrupt syndicates directed by powerful unions beholden only to the thin blue line. Los Angeles Police Protective League spokesman, Jamie McBride, is a Bigfoot Bjornsen-type hobgoblin who, when faced with possible budget cuts to the LAPD, called Garcetti “mentally unstable.” Of course, he also posts Facebook videos yearning for the “good old days” when cops freely body slammed and tasered Black and Latino suspects. Decades of would-be rehabilitation have done little good: by all accounts, the LAPD and L.A. County Sheriff’s Department remain paramilitary organizations founded on white supremacy, gleeful violence, and a code of omerta.

Somehow, the chief mutant of the Suicide Squad is Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva. Rightfully called “The Donald Trump of law enforcement,” Villanueva was a lightly regarded lieutenant who narrowly won a 2018 election by touting himself as a Democrat reformer who would kick ICE out of county jails. It was only the first of many mistruths. Technically, ICE is no longer “inside” the jails, but deportation transfers between L.A. law enforcement and ICE still exist. They’re now conducted through intermediaries, 80 feet away from the original handover spot. Villanueva has rehired a deputy fired for domestic abuse, ignored court-ordered subpoenas, and flouted reasonable attempts from the County Board of Supervisors to reign in his abuses of power. When the Office of Inspector General accessed confidential personnel files of Villanueva and other top brass, the Sheriff shot back by launching a criminal investigation into the watchdog agency.

“The Sheriff keeps on describing himself as a ‘progressive,’ but he’s more problematic than any sheriff that I’ve known,” says the august County Supervisor, Sheila Kuehl. “We have significantly cut the budget — not to zero, but the Sheriff’s department took the biggest hit, an 8 percent curtailment. He stands to lose between 400 and 700 deputies. Even before the public calls for defunding, we were already trying to right-size the department. ”

While reformation attempts have largely focused on the LAPD, the Sheriff’s Department has racked up arguably an even more startling record of atrocities. The largest sheriff’s department in the country and the fourth-largest law enforcement agency overall, the LASD siphons away a yearly budget of roughly $3.5 billion. Somehow, a civilian oversight commission wasn’t created until 2016, two full years after former Sheriff Lee Baca resigned amid allegations of sheriff abuses in the county jails. (Today, he withers away in a federal prison on charges of obstructing an FBI investigation into these abuses.) In 2018, the L.A. Times published damning revelations that the LASD had run a vast racial profiling scheme on Interstate 5, pulling over a heavily disproportionate amount of Latinx drivers in search of drugs. And at the moment, the Feds are investigating a secret society of tattooed L.A. Sheriff’s gang members, one of which a judge once referred to as a “neo-Nazi white supremacist gang.”

The LAPD have worn mandated body cams since the middle of the last decade, but so far, the Sheriffs have eluded them. Villanueva blames it on the Supervisors, but Kuehl says that the chief hold up is that Villanueva is demanding that deputies be able to watch the footage first before being forced to turn it over to investigators. Villanueva is up for reelection in 2022; a better future requires not just calls for defunding the police, but a suitable candidate to defeat him.

Despite the grim times, a rare beacon of light emanated from a July Board of Supervisors vote to explore what it would take to close downtown’s hellish Men’s Central Jail within the year — a place that the ACLU famously described as “a modern-day medieval dungeon, a dank, windowless place where prisoners live in fear of retaliation, and abuse apparently goes unchecked.” It remains unclear what will replace it — and bureaucratic wrangling and delays are certainly inevitable — but it’s a major first step towards building a more humane system.

“At least half the people currently in jail don’t need to be there,” Kuehl says, referring to the high percentage of the jail population that consists of the chronically homeless, mentally ill, and chemically addicted. “We want them diverted, but that means really stepping up the planning to create beds for those with mental health and substance abuse problems. In the meantime, we’ve started downsizing the contract with the jail.”

If the fixation on the police appears monomaniacal to outsiders, a closer examination reveals how entrenched law enforcement has become in the machinations of city politics. One of the most prominent flanks of the progressive movement of the last few years has revolved around the push to cancel the 2028 Summer Olympics. As it stands, the private sector has agreed to foot the bill, but the city of L.A. is set to pay the first $250 million of cost overruns.

“Having 2028 on the calendar threatens to undo all the work done to defund the police and will only increase surveillance,” says Spike Friedman, an organizer with Ground Game L.A. and NOlympics L.A., the latter of which is a grassroots group aimed at dismantling the looming event. “The LAPD has said they need 3,000 more full-time officers. It requires coordination between the federal and local government that allows ICE to get their tendrils into L.A. in ways above and beyond what we’ve ever seen. It will be an accelerator of mass displacement.”

There are so many pressing problems that it can be difficult to know where to begin or end. So many that they didn’t fit into this article: the crimes of wage theft and the failure to close down the Aliso Canyon oil field; our mass transit remains insufficient; our public schools woefully underfunded; the pandemic response has been disgraceful; and the influencers and YouTubers who hike Runyon Canyon continue to exist.

In its failures, L.A. is inextricable from the incendiary madness of a society rooted in greed and racism, both deceptive and overt. A crumbling republic led by a doddering bronzed chickenhead, policed by petulant sadists, and balkanized by ghoulish propaganda networks. A gleefully unequal and paranoid tomb squandering trillions on futile militarism while letting its own citizens frantically crowdfund to pay off medical debt. There are hundreds of thousands dead from a pandemic, their grieving families unable to even bid farewell with a proper funeral — largely due to the incompetence that began at the top but has ensnared nearly every elected official. It is supposed to be different, but too often that illusion is just slick marketing. Maybe this time things will change, that this next generation can fix the gilded lunacy and asphyxiating prejudice that has triggered our swift decline.

There are no easy solutions, but the only conceivable fixes require organization, intense commitment, and the messianic belief in the possibility of redemption. L.A. not only needs a new generation of incorruptible and creative politicians, it needs righteous-minded housing authority executives and urban planners, parks commissioners and homeless services workers — a desire to revitalize a lifeless civil service trapped in bureaucratic languor.

The institutions of the past are irrelevant. Without new ones to replace them, there will eventually be nothing. And it will always have to be the people to change things, because if not, it will be the CEOs and the sheriffs. Eventually, there will be no more chances, the situation will erode to where there is no path of return. In that case, there is only forward.