“They say that there’s a choice between the people and the economy,” David Kim screamed into a megaphone, beads of sweat forming around his temples. “Well guess what? Why are we here now?” he shouted, his voice growing louder. “We’re here to say we are the fucking economy!” Kim beat his open palms on his chest as he let out these last five words, the crowd erupting in cheers. By that point, more than two minutes into an increasingly heated speech, Kim had already thrown his cardboard sign — “people over profit” it read in black sharpie — to the ground and torn off his black face mask so he could more fully express his anger.

It was a warm Sunday in July and Kim had plenty of reasons to be angry: cases of a deadly pandemic were surging after L.A. County’s brief but disastrous re-opening of bars and restaurants; nearly one in five Angelenos were unemployed; and there was no economic relief in sight following a one-time round of $1,200 checks issued months earlier as part of a stimulus package that largely benefited corporations.

Kim’s speech took place at one of dozens of left-leaning nationwide protests staged in front of the homes of Senators and Congresspeople to demand benefits such as $2,000 monthly cash payments, Medicare for all, and a suspension of rent and mortgage payments (The demands have been unsuccessful). Targets included Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, Republican Senator Ted Cruz, and Democratic Congressman Jimmy Gomez, on whose well-manicured driveway Kim was pacing back and forth. Kim, however, wasn’t just an activist or a protester plucked from the crowd; he is running for Gomez’s seat in the 34th Congressional District in Northeast L.A.

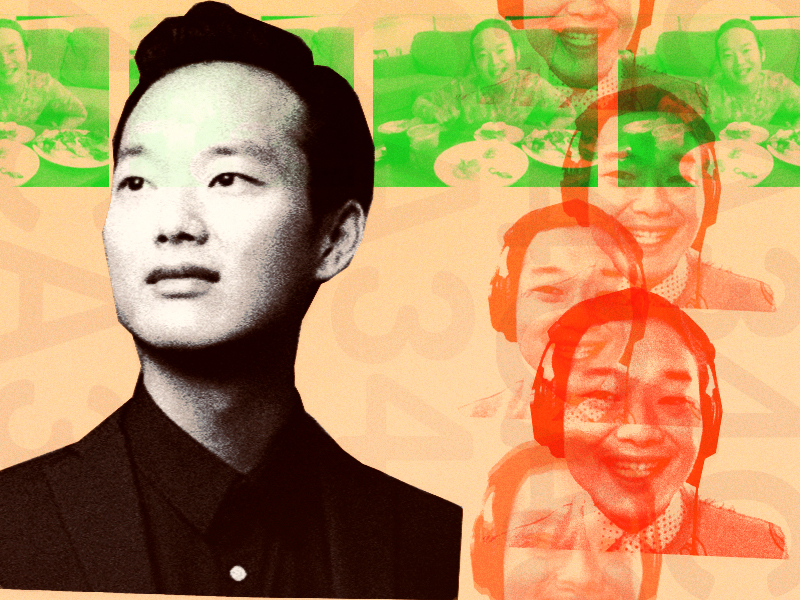

“I had no idea I’d be cursing like that, and after I was done I apologized to some campaign volunteers. I was like, ‘I don’t know what got over me, I apologize, but there’s your speech,’” Kim, wearing a sweater patterned with cartoon donuts, says on a recent Zoom call, laughing and covering his face with slight embarrassment. He says that when he’d been asked to speak at the event by Our Revolution L.A., the local chapter of the political organizing group that grew out of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, he planned to say just a few words. But “as soon as I started, I got so angry to the core of the deepest depths of my soul,” he recalls, launching into a long-winded rant about his opponent, whom he believes “represents a clear caricature of our corporate officials in government.”

Kim, a 36-year-old immigration attorney, is among a new crop of progressive, first-time candidates who are challenging Democratic incumbents in solidly blue Congressional, Senate, and Assembly districts throughout California. He champions Medicare for All, the Green New Deal, and a universal basic income. An archetypal Millennial, he’s driven for Uber and Lyft to make ends meet, says he’s still paying off student loan debt from college (he has a B.A. in history from University of California-Berkeley and a J.D. from Yeshiva University Cardozo School of Law), and is really good at making YouTube videos. In April, he launched a mukbang series — based on the popular Korean genre in which people film themselves eating massive amounts of food — with a charitable twist: Each video is meant to promote a local restaurant affected by the pandemic; he also asks his viewers to sponsor meals from the restaurants so he can distribute them to people experiencing hunger and homelessness.

His political idols include former Democratic presidential candidates Marianne Williamson and Andrew Yang, both of whom have given him their endorsements in an uphill race against Gomez. The Democratic incumbent’s campaign has raised almost six times as much money as Kim’s grassroots one — making Gomez’s re-election more than likely — but it’s Gomez’s corporate fundraising that Kim says is precisely the problem. “He shows up at Black Lives Matter protests doing a photo opp not knowing that his taking private prison money is horrible and enabling all this because he’s profiting off human suffering, he’s profiting off police PACs,” Kim says. (Indeed, a photo of a masked man that appears to be Gomez marching in the streets of Highland Park last summer was featured on one of his recent mailers.)

Gomez’s campaign contributions have become a recurrent source of criticism from his progressive challengers, including Kenneth Mejia in 2018. Between his 2012, 2014, and 2016 runs for California State Assembly, Gomez accepted at least $5,000 in contributions from CoreCivic — which owns and operates private prisons and ICE detention centers — and more than $7,500 in contributions from the Los Angeles Police Protective League, according to listings on the political watchdog website Follow the Money. More recently, however, the roughly $1 million Gomez has raised comes primarily from the energy, finance, real estate, and health insurance industries — Blue Cross/Blue Shield is among his biggest donors — according to the nonpartisan campaign finance website Open Secrets. (Gomez’s campaign did not respond to request for comment about these contributions.)

While none of these campaign donations are exactly unique to Democratic politicians — Gavin Newsom accepted $5,000 in donations from CoreCivic during his successful 2018 run for governor, according to Follow the Money — they certainly aren’t part of the image Gomez’s campaign portrays on its aggressive barrage of glossy mailers. The materials instead play up Gomez’s working-class background as a child of Mexican immigrants; his mother was a nursing home laundry attendant and his father was a bracero and a farmworker, he wrote in an anti-Trump op-ed in the Washington Post just after his election to Congress in 2017. (He won in a special election to replace Xavier Becerra, who vacated the 34th District seat to succeed Kamala Harris as Attorney General; he failed to show up to work for weeks after being elected, skipping out on crucial votes on federal immigration policies, according to the Washington Post.) Adding to his Democratic clout, he was endorsed this year by the influential labor union United Farm Workers of America and received a significant campaign donation from the United Food and Commercial Workers Union, which represents more than 1 million workers across the country.

On Wednesday, Oct. 14, some voters in Los Angeles — myself included — received a text message that appeared to be from Gomez’s campaign. “Bernie Sanders’ Our Revolution just announced they officially endorsed Jimmy Gomez,” it read. “We can count on Jimmy to stand with Bernie and fight for our progressive values. Vote Jimmy Gomez for Congress!” The message, sent from a disconnected phone number, included the official Our Revolution illustration of Sanders raising his fist into the air. It immediately caused confusion not only because there was no evidence of the endorsement anywhere on Our Revolution’s website or social media, but also because Our Revolution L.A., the local chapter of the organization, had already made an endorsement in the race — and it was for Kim.

The endorsement, in fact, appears to be legitimate, according to an Our Revolution email that was forwarded to me by Bertha Guerrero, Gomez’s chief-of-staff. (Our Revolution did not respond to requests for comment, nor did Our Revolution L.A.) The endorsement highlights a rift between the national political action group and its local offshoot, which had previously issued a statement on Twitter suggesting Gomez’s campaign was falsely touting an endorsement from three years ago. “This week, I was made aware that the national arm of Our Revolution endorsed his bid for reelection, but this decision was made without the consultation of their local branch, Our Revolution L.A., which has supported my campaign since June of this year and continues to proudly do so,” Kim said in an emailed statement. “I am so grateful for their determination and willingness to get involved at the ground level and advocate for the same community-first policies that have brought so much energy and enthusiasm to my campaign.”

Kim’s quest to unseat Gomez is personal: It dates back to his time volunteering for Mejia’s campaign in 2018, which Kim says awakened him to the power of grassroots organizing. It all started with a text message. “In the text he said, ‘Hi my name is Kenneth Mejia, I’m 26 years old, I’m Filipino-American, and it doesn’t make sense that our government is working against us,” says Kim, who remembers Mejia supported universal health care, a Green New Deal, and a cancellation of student debt. “I thought, ‘Whoa, this guy’s younger than me, he’s so much more of a visionary, he’s bold, he’s passionate,’ so that really got me going and I ended up volunteering for his campaign. I fell down the rabbit hole and coordinated a lot of stuff for him.”

Mejia, a Green Party candidate, lost in a landslide to Gomez. Kim found it “heart crushing,” but he also saw a bright spot: Mejia had scored more than 25% of the vote as a Green Party candidate in a district where few voters were registered members of the Green Party; if Mejia had run as a Democratic Party candidate, Kim thought, the election may have gone differently.

Last May, Kim made his first foray into electoral politics when he was elected president of his neighborhood council in MacArthur Park; A month later, he registered as a Congressional candidate under a political committee named Financial Freedom, Love & Justice For All. “I’m a very recent activist organizer,” he admits. “When I share my story, people who have been organizing for 15, 20 years, they’re like, ‘Oh you’re a baby!’”

Kim took an unlikely path to politics. He grew up in a religious family that moved around the country every time his dad found a new job as a pastor. He spent the first five years of his life in Sierra Vista, Arizona, where his Korean immigrant parents had decided to overstay their temporary visas after his dad got a job as a pastor at an immigrant church there. Next came a move to Tacoma, Washington, followed by San Jose, California.

Throughout his childhood, Kim says, he experienced racism at school and physical abuse at home. “I think it just came from my dad’s own childhood growing up and the inferiority complex that he developed, where every time he thought that one of his sons was rebelling, he took that as a personal thing,” Kim says. “I was also struggling with my identity in terms of, obviously kind of being gay in the closet, and so I didn’t share that with my parents up until a few years ago and we didn’t talk for a couple of years because of that.”

Eventually, Kim went to law school — an idea his father had planted in his head from a young age — and moved to Los Angeles after getting a job at the L.A. County District Attorney’s office in 2010, under D.A. Steve Cooley. “I worked in the Public Integrity Division and it was a division that worked on cases prosecuting corrupt, public officials,” says Kim, who is eager to clarify that he did not work with Jackie Lacey, Cooley’s successor, who has is under fire from activists for failing to prosecute cops for murder.

When his gig with the county ended, Kim took a job at a labor and employment litigation firm in Pasadena, but says the pay was so meager that it drove him into debt; he soon began driving for Uber and Lyft after-hours. “That was the hustle that I did, because if you have a hole in your legal resume, you won’t be hired anywhere,” Kim says.

In 2014, after watching his friends who were aspiring writers, directors, and actors get ripped off on contracts and “charged an arm and a leg” by the lawyers they hired to review them, he founded his own firm that specialized in offering affordable legal services to creatives. Eventually, he was able to make enough money to quit his side gigs, which to him “felt like an amenity that only rich people have.” It was a feeling that he resented. “Everybody should be able to have time to think and breathe after work and not just run off to the next job,” he says.

It’s the kind of experience — not uncommon for thirty-somethings who graduated college into a recession and have hopped from one independent contractor gig to the next or juggled multiple gigs at the same time — that shapes Kim’s outlook as a Congressional candidate. “We can’t have career politicians because they haven’t worked a job in other industries,” he says. “They don’t know what it’s like.”

For now, Kim, working out of a Koreatown campaign office he says he’s subleasing “for dirt cheap” from a previous legal client, is focused on making phone calls and texts — and delivering the occasional protest speech, when he’s not making videos. (Earlier this week, he posted to Twitter his own version of the viral Tik Tok by cranberry juice-swigging skateboarder Nathan Apodaca.) Whatever happens after the election, Kim says, “we still need to keep pushing” to make politics more transparent and to get more people engaged in it.

It’s something he’s become convinced of after having made countless calls to voters to tell them he’s running for Congress, only to be met with a dial-tone. “It’s sad because they just treat you as a sales call, when it’s actually something that they should be very interested in,” Kim says. “Because when you turn off the light, this is politics. When you get your paycheck, that’s politics. When you flush your toilet that’s politics.”

What keeps Kim going is the hope that for every handful of people who hang up on him and his volunteers, there could be many more willing to listen. It’s not unthinkable, after all, that Kim’s call might be as transformative to somebody as Mejia’s text message was for him two years earlier. It’s possible that one of Kim’s calls could even inspire a future candidate.

theLAnd Voter Guide

- Immigrant Activists Have Given Me More Hope Than the Democratic Party

- The Progressive Challenger Who Wants to Unseat a Democratic Titan

- Endorsing the Lesser of Two Evils in this Stupid, Sad, and Fake Election

- A Conversation With Kendrick Sampson on Activism and Police Abolition

- Jackie Lacey Vs. The People

- The L.A. Politicians With More Power Than the Mayor

- A Battle for the Soul of California: An Oral History of Prop 15

- Godfrey Santos Plata Wants to Stand Up to Your Landlord

- Fatima Iqbal-Zubair is the Antidote to 2020 Pessimism

- Holly Mitchell is Ready to Take on Los Angeles

- Is George Gascon Really the Godfather of Progressive Prosecutors?

- L.A. Progressive Voter Guide

- Nithya Raman, the Progressive Candidate Running for City Council