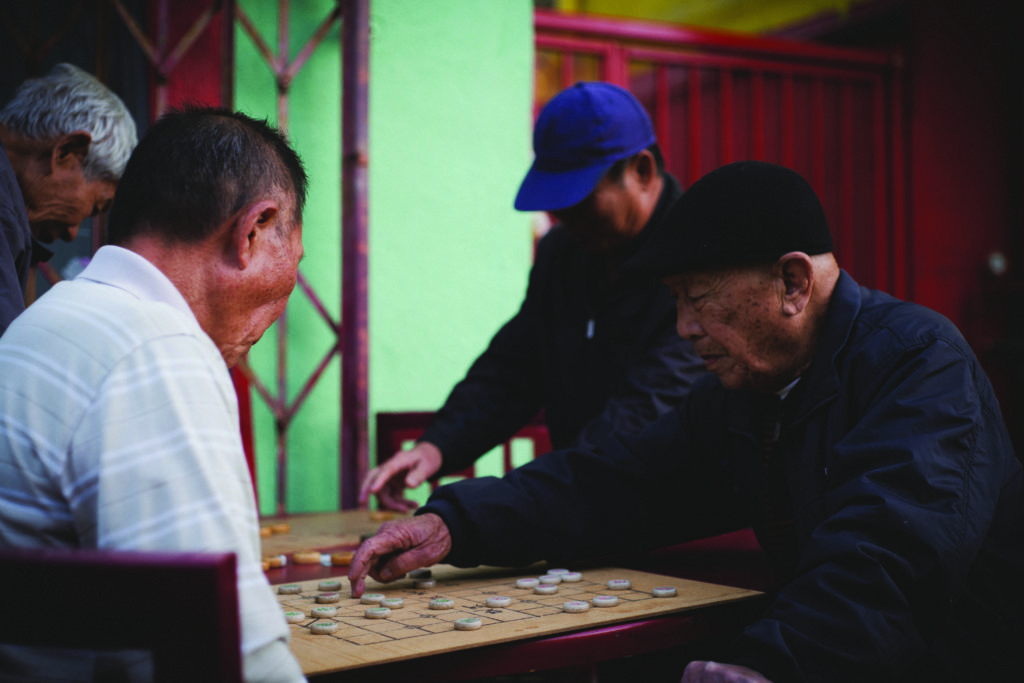

XL Middleton is watching the daytime mahjong players outside his record shop on Mei Ling Way. Hunched and sun-dried, cloaked in a corona of cigarette smoke and Cantonese banter, the players are remnants of a vanishing world.

Chinatown is gentrifying, and with wealthier Chinese immigrants overwhelmingly choosing the suburban comforts of the San Gabriel Valley, centuries-old customs like mahjong feel incongruous in an enclave awash with art galleries and stylish restaurants. Middleton – a Pasadena native and modern funk innovator of Hawaiian extraction – is keenly aware of his place in the shifting cosmology of Chinatown.

“I have to stop and check myself, like ‘Am I behaving like a gentrifier?’” says the producer and label owner, whose record shop, Salt Box Records, replaced a travel agency in July 2017. “I think one of the most important things to not be that person is to interact with the community that’s already here. Even though the shop’s been open for over a year, I’m still a guest in a lot of ways. All those guys at those tables, playing mahjong, they’ve been here and I think it’s important to respect that.”

Middleton, who had long dreamt of opening a record store in Chinatown, isn’t the first musician to be smitten with the neighborhood’s kitsch and arcana. In the late 1970s and early ‘80s, rival nightclubs situated across from each other on Gin Ling Way, Madam Wong’s and the Hong Kong Café, hosted scores of influential punk, hardcore and New Wave bands.

Between 1998 and 2009, ethnically diverse, like-minded DJ’s and visual artists gathered at Grand Star Restaurant for Firecracker, confusingly held on the first, third and fifth Friday of every month. For several years in the early 2010s, the Beat Swap Meet — a dude-ly assembly of vinyl obsessives — was held in the shadow of Central Plaza’s Bruce Lee statue. Each generation of hip Angelenos is charmed anew by Chinatown’s cramped alleyways, curling pagodas and bobbing paper lanterns because, in a city defined by ravenous newness, time has afforded the neighborhood a comforting historicity.

“The thought of writing whole verses that were just sung and not rapped –– when you come from a hip-hop background that feels like such a big jump,” Middleton says. “Especially coming from the ‘90s era […] It took some time, having songs in the vault. I had to be content with ‘Maybe I’m never going to put this out, but it’s a stepping-stone to something that’s going to be better.’”

“I have to stop and check myself, like ‘Am I behaving like a gentrifier?’ … Even though the shop’s been open for over a year, I’m still a guest in a lot of ways. All those guys at those tables, playing mahjong, they’ve been here and I think it’s important to respect that.”

Middleton’s music satisfies these same desires. His work is a bright Southland amalgam of boogie’s squiggly synthesizers, funk’s lusty slap-bass bump, and G-funk’s unyielding hydraulic bounce. It sounds like: the giddy chatter of springtime’s first barbecue; a pungent sidewalk weed waft of unknowable provenance; a dramatic purple-orange dusk revealing itself as you crest Sunset Boulevard; the odd and ambient melancholia of trying to live in Los Angeles, a denuded and dehydrated should-have-been paradise. It was in modern funk that Middleton (who spent his childhood playing Scott Joplin’s ragtime compositions and most of his adulthood producing for rappers) found himself.

“The thought of writing whole verses that were just sung and not rapped –– when you come from a hip-hop background that feels like such a big jump,” Middleton says. “Especially coming from the ‘90s era […] It took some time, having songs in the vault. I had to be content with ‘Maybe I’m never going to put this out, but it’s a stepping-stone to something that’s going to be better.’”

It was his discovery of modern funk creator Dam-Funk that led Middleton, who’d long associated “nightlife” with the soulless bacchanalia of Hollywood nightclubs, to Funkmosphere. During its 11-year run, Dam-Funk’s Funkmosphere was an unpretentious, eminently groovable weekly gathering of synth-funk devotees. There were unselfconscious pop-locking dance circles, slow-vibing oldheads, and, just once, Faith Evans in a KISS T-shirt. It was where an idea conjured in Dam-Funk’s analog, gear-cluttered bedroom became real and where another Pasadena native, Eddy Funkster, DJ’ed.

Had a friend of Middleton’s not reached into the “Free” box at Pasadena’s Poo-Bah Records and grabbed an Eddy Funkster CD in 2011, modern funk might be drastically different. The erstwhile partnership between Middleton and Funkster was a driving force in the scene: their EP, XL Middleton + Eddy Funkster, is a modern funk standard and the label they co-founded, MoFunk Records, has released albums by talkboxing San Francisco polymath Diamond Ortiz, Pasadena songstress Moniquea and cocaine-dealer-turned-SpaceX employee Zackey Force Funk. (As of this writing, Funkster is no longer involved in MoFunk.)

“You can tell that he’s a sweetheart when you meet him,” Zackey says of Middleton in quick-clipped diction. “He’s got a good ear for different sounds of funk, and when it comes to boogie sounds he’s one of the best, if not the best. You can just see that everyone’s got their own style in modern funk – which is a great fuckin’ thing – but when it comes to cholo, boogie, lowrider funk, I think he’s doing it the best.”

Although Middleton prefers to work in isolation because, as he says, he has “little thought bubbles that get popped easily,” Moniquea, like Zackey Force Funk, has benefited from his exacting ear. But, unlike Zackey, who was initially loath to let Middleton edit his acapellas, Moniquea and Middleton’s process was less charged. With two albums largely produced by Middleton (Yes No Maybe and Blackwavefunk), Moniquea, who has the voice of a Jones Girl, has nearly a decade of experience working with Pasadena’s most amiable keyboardist.

“They say ‘funk is freedom’ and I believe that. I think that there’s something in the quirky synthesizer squiggle.”

XL Middleton

“He’s very easy to work with. It probably stems from his general good-hearted nature. It’s fun […] We started working together at the end of 2010, early 2011, I kind of got used to his to his style and production early on,” Moniquea says. “That was something we learned together: what my vocals should be like.”

Middleton’s kindness seems to be infectious––the modern funk scene is less concerned with technical perfection or the cultivation of individual stardom than it is with openness, diversity and positivity. For artists like Middleton, Zackey Force Funk (who oversees the making of composites at SpaceX by day) and Moniquea (an office specialist and funding coordinator for City Councilman David Ryu), modern funk is a cooperative and spiritual pursuit.

“It’s a scene that’s actively trying to create space for people to come together and feel like they can be themselves,” Middleton says. “They say ‘funk is freedom’ and I believe that. I think that there’s something in the quirky synthesizer squiggle. When you hear a synth go bew-bew-dew-duh-nyew-nyew, that might make you feel kinda silly in a way. That might make you feel like busting a move on the dance floor that you might not do normally.”

Of all the available visions for Los Angeles, this is among the most harmonious. And from a bright yellow, red, and turquoise storefront, Middleton creates a space for it. One Sunday per month, a rotating cast of DJs sets up outside Salt Box Records and serenades Mei Ling Way’s curdled mahjong players with pastel synthesizers and roiling bass licks.

But where DJ and mahjong players bicker, there once sat Little Italy, where Apulians, Calabrians, and Sicilians wasted afternoons on Briscola, a card game likely taken from Dutch sailors. And, before provincial Chinese and Italians, there were fields riven by the zanjamadre, the aqueduct which brought water to the pueblo. And before the conquistadors, who arrived with a city grid copied from the Archive of the Indies in Seville, there were Tongva, with willow reed huts and morally ambiguous gods. And now XL Middleton, a beatific half-white, half-Hawaiian-Japanese funkster and record merchant.