In a more reasonable America, John Rechy would be as iconic as Jack Kerouac. Posters of Rechy’s matinee idol profile would adorn dorm room walls, brooding above poetic aphorisms capturing the dissonant orgy of modern life. Oscar-winning directors would have spent a half century vying to bring his gay-hustling odyssey to the big screen. At some point in the ‘90s, a flavorless clothing behemoth would surely have tried to appropriate his image to sell khakis.

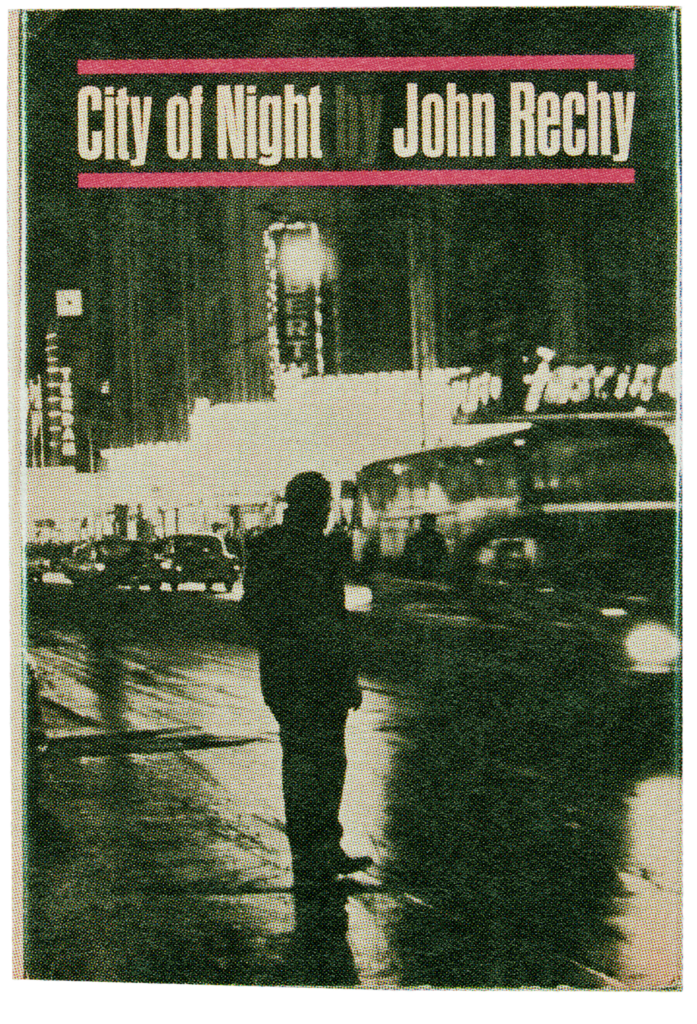

But while Kerouac’s 1957 countercultural opus was immediately greeted with voice-of-a-generation praise, Rechy’s 1963 debut, City of Night, was met with derision, bigotry and regular placement on banned books lists. An eviscerating takedown from the period in The New York Review of Books began with the derogatory headline “Fruit Salad” and continued like something out of a “Save the Children” literary supplement, full of homophobic epithets and excruciating puns. The critic even cast doubt on the existence of the Mexican American Rechy, who had written the novel on a typewriter in his mother’s house in the El Paso projects. Despite a taboo-shattering six-decade career spanning 18 books and counting, Rechy has been regularly hounded by such misapprehensions.

That’s not to say that posterity won’t enshrine Rechy as a glamorous icon of carnal liberation. The 90-year-old laureate of sex and salvation is L.A.’s greatest living writer. Despite the initial opprobrium, City of Night sold 65,000 copies in hardcover and spent over half a year on The New York Times best-seller list, alongside J.D. Salinger and Pearl S. Buck — who had previously rejected Rechy from her creative writing class at Columbia. (And to be fair, the paper of record immediately hailed City of Night as “a remarkable book.”) In the nearly 60 years since, City of Night has never gone out of print, has been translated into over 20 languages and has entered the same smoky, red-lit corner of the outlaw literary Olympus as On the Road, “Howl” and the best of Jean Genet.

The list of legends bestowing praise on Rechy doubles as a 20th century pantheon. James Baldwin called him “the most arresting young writer I’ve read in a very long time. His tone rings absolutely true, is absolutely his own.” Gore Vidal said Rechy was one of the “few original American writers of the last century.” Larry McMurtry declared, “Probably no novel published in this decade is so complete, so well held together, and so important as City of Night.” Christopher Isherwood raved that Rechy had “great comic and tragic talent. He is a truly gifted novelist.”

David Bowie, Mick Jagger, and Bob Dylan have all expressed deep admiration, while Jim Morrison took direct inspiration from Rechy in the doomed refrain of the Doors’ “L.A. Woman.” David Hockney’s painting Building, Pershing Square, Los Angeles draws from Rechy’s portrayal of that same locale. At least one Oscar-nominated director, Gus Van Sant, whose film My Own Private Idaho owes a clear creative debt to Rechy’s hustler narrative, has in fact attempted to produce a City of Night movie.

None of the praise or devotion is remotely hyperbolic. City of Night remains as relevant as it was the year Kennedy was assassinated. In an era where gender and sexual identity figures centrally within the zeitgeist, Rechy wrote with tender insight, prodigious empathy and Rimbaudian grace about what is now known as the LGBTQ community. His depiction of the “Fabulous Miss Destiny” implicitly framed gay marriage as a human rights issue at a time when it was legally prohibited for same-sex couples to even swing dance together. Over a half-century before OnlyFans, Rechy offered one of the most thoroughly humanizing portrayals of sex workers in the history of (even if he reviles the euphemism “sex worker” because he insists that for him, “it wasn’t work”).

With startling clarity and seraphic prose, Rechy illuminated a gay subculture, then called “the homosexual underworld,” that flourished despite the repression. His dispatches from New Orleans and Los Angeles rank among the finest fiction to ever capture the sun-damaged moods and mercurial spirits of those infamously complex cities. And as a young gay man facing intense prejudice, physical harm and police brutality, his work powerfully indicts the hysterical madness of the American criminal justice system. As a stylist, he’s violently imaginative and meticulously precise — carefully blurring fact and poetic license in a way that foreshadowed the rise of autofiction.

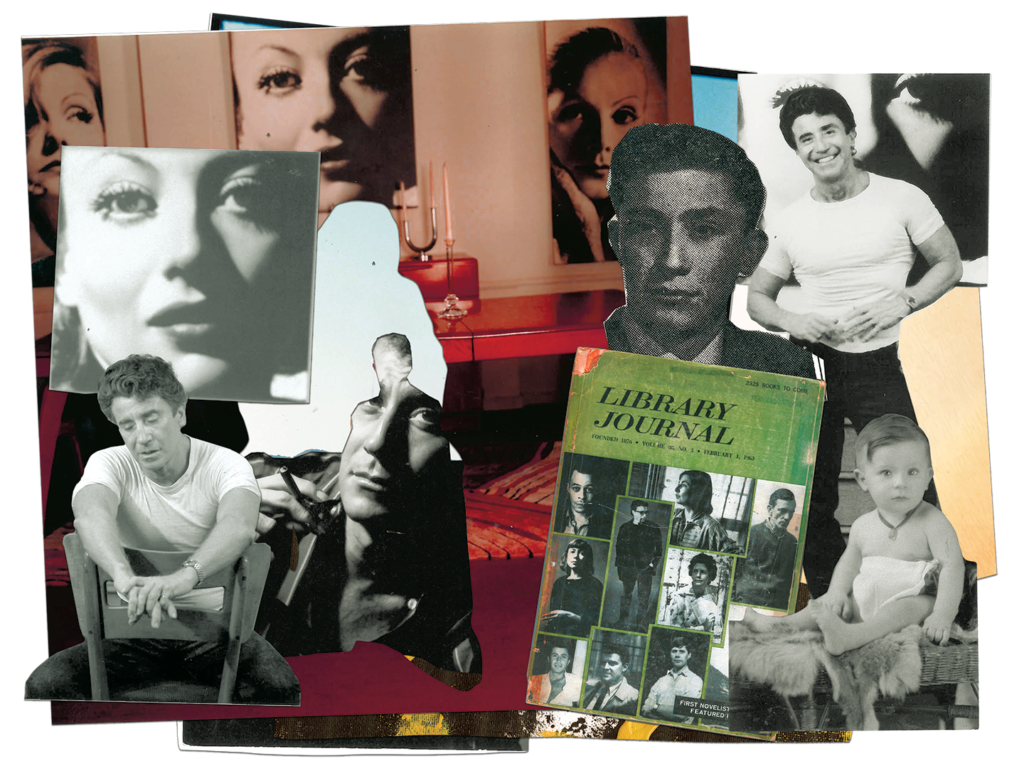

For most of the last six decades, the City of Angels has been the City of Night author’s home, but the saga begins in El Paso, where Rechy was the youngest of five, born to two Mexican émigrés who fled the capital during the Revolution in 1910. His father, Roberto, was a composer of Scottish descent, a tormented and abusive philanderer who found himself indigent and unable to sustain his art in his adopted homeland. John’s beautiful mother, Guadalupe Flores, offered profound love and support to her artistic and strikingly handsome son, whose scholastic excellence blazed a path out of the barrios of West Texas. Early in his teenage years, he began a novel about Marie Antoinette and swiftly absorbed a reading diet of the Greek tragedians, Dostoevsky, Emily Brontë, William Faulkner and the popular semihistorical novelists Kathleen Winsor and Margaret Mitchell. Comic books and the luminous movie stars of Hollywood’s golden age factored into the prodigal son’s influences, too.

The themes that would characterize his later work are endemic in his first 18 years: the conflicts with the sadistic shame and pornographic iconography of the Catholic Church, the splendor of youth and the fear of aging, a desire for filial approval that led him to forge a self-assured and unbreakable façade, the glamour of Hollywood, the rituals and fantastic images of pre-Colombian Mayan lore, the cool carnal lust, the essence of mystery, the fight against racism and withering homophobia and the unshakable desire to transcend the banalities of this earthly oblivion.

After graduating from Texas Western College (now the University of Texas-El Paso) on a journalism scholarship, Rechy volunteered for the Army. During the Korean War, he was stationed in Kentucky with the 101st Airborne Division. His hustling career began afterward, in the New York of 1954. He was 23. For the next half-decade, he lived a nomadic lifestyle, splitting time between San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles and Texas. Exhausted by the dual existence, he returned home to El Paso and redoubled himself to writing after being published in the Evergreen Review, the fabled journal then printing work from the Beats, Henry Miller, Genet and Samuel Beckett. Originally written as an unmailed letter to a friend, the short story “Mardi Gras” became a sensation and drew attention from publishers. With every printed piece his star rose, leading to letters of admiration from Isherwood and Norman Mailer and nonfiction assignments from The Nation and the Saturday Review.

Despite the demeaning NYRB review, City of Night became a phenomenon. Careful to avoid the infernal celebrity machine that consumed Vidal, Truman Capote and Kerouac, Rechy declined the television interview circuit. Purchasing a home for his mother outside of the projects, he settled with her in El Paso, worked on a never-published sequel to City of Night and took occasional trips to California, where he discovered the cruising scene at Griffith Park. This world served as the principal setting for 1967 best-seller Numbers, a tale of a hustler who allays his neuroses about aging by racking up a sexual body count worthy of Lord Byron. A 1966 arrest in Griffith Park for “oral copulation” added to the infamy; an inspired defense at his subsequent trial, chronicled in the 1970 novel This Day’s Death, allowed him to beat the case and avoid up to five years in prison.

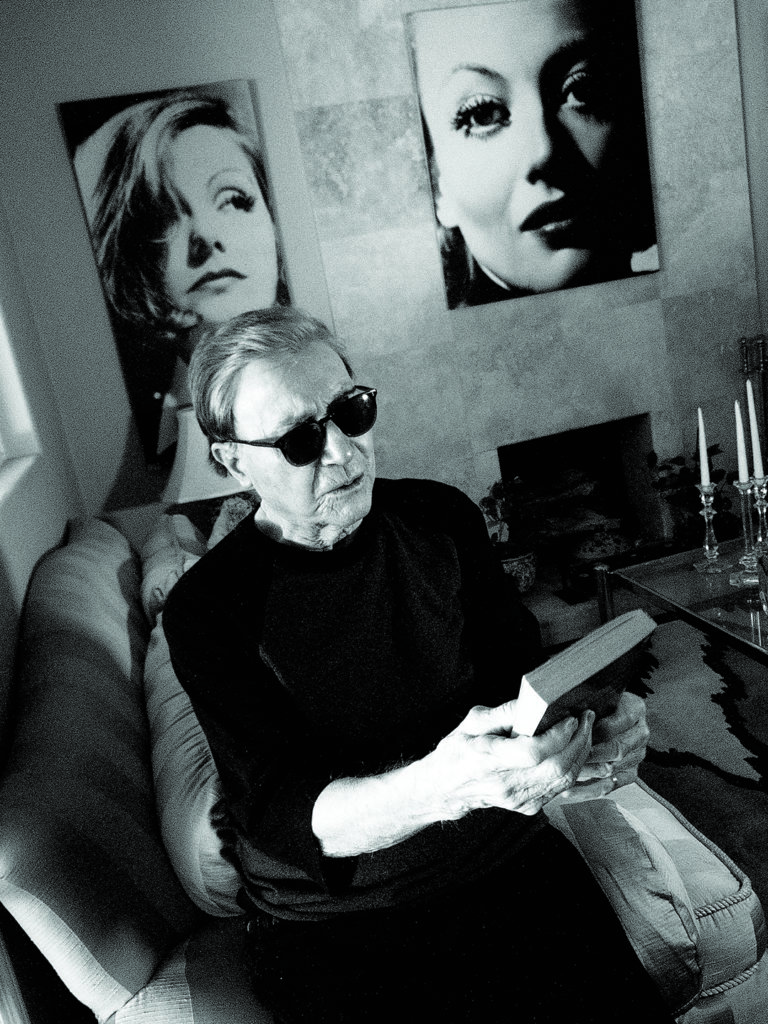

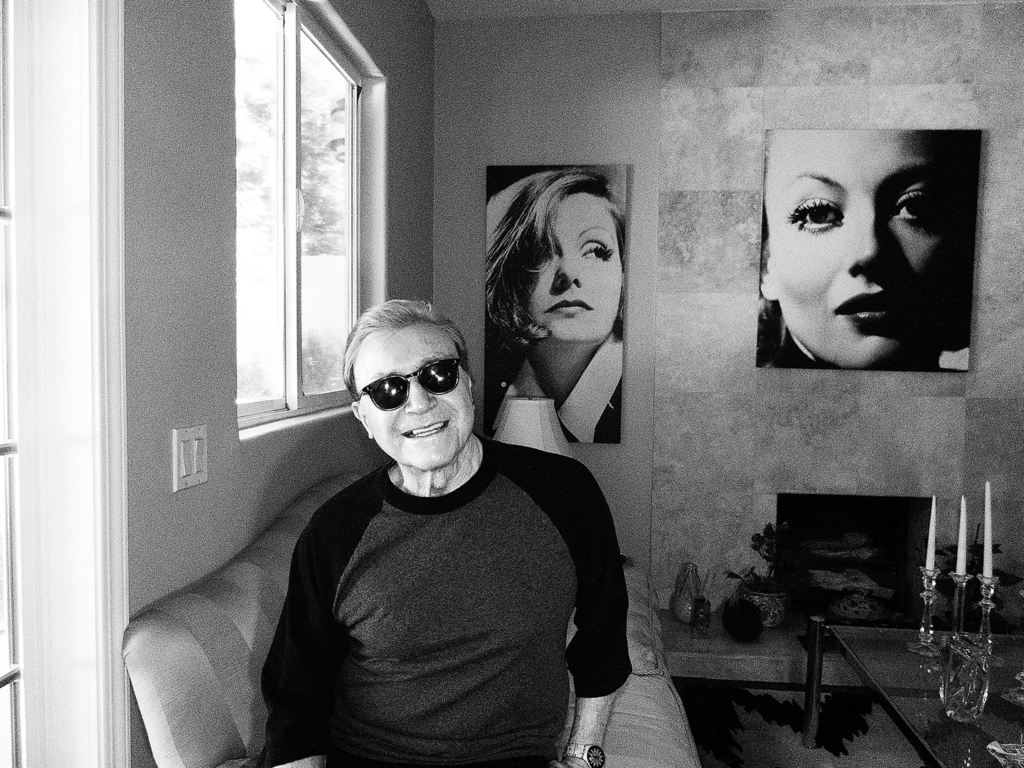

El Paso remained his permanent residence until 1973. Beset with primordial grief over the loss of his mother, Rechy moved back to L.A. to accept a position as a creative writing professor at Occidental College (he would eventually lecture at Harvard, Yale, Duke, UCLA and USC). His students have included Michael Cunningham, Kate Braverman and Sandra Tsing Loh. Hustling remained a perennial nocturnal activity until roughly age 60; perhaps fittingly, it’s how he met his longtime mate (the word Rechy prefers to “partner”), Michael Ewing, with whom he lives in an elegant Encino home at the end of a cul-de-sac. There are bountiful lemon trees in the backyard and blown-up black and white lithographs of Joan Crawford, Marilyn Monroe and Greta Garbo inside, gorgeously suspended in permanent, pre-war allure. In a classic L.A. twist, the city’s long-reigning laureate lives with the producer of Tommy Boy, the Naked Gun sequels and several Adam Sandler vehicles.

It’s tempting but misguided to reduce Rechy to The City Of Night and other works.

With the benefit of time, the sprawling genius of Rechy’s career comes into clear focus. A true American original, he has penned an erotic vampire chronicle in homage to Edgar Allan Poe (The Vampires), a feminist redemption for the fallen women of history (Our Lady of Babylon) and a historical “what if” scenario about the love child of Marilyn Monroe and Robert F. Kennedy (Marilyn’s Daughter). There are multiple collections of essays and journalism, as well as an elegiac memoir (About My Life and the Kept Woman). His most recent new work, 2017’s After the Blue Hour, a subtle psychosexual chronicle of a long-ago love triangle, ranks among his best. At the moment, he’s working on Beautiful People at the End of the Line, a wry satire about a lurid and corrupt woman named the Countess who schemes to turn two virgins into the biggest porn stars in America. As his 10th decade dawns, his mind remains enviably sharp, and his insights are perennially astute. He’s still tanned from the Valley sun and regularly pumps iron in his home gym.

It’s not that Rechy hasn’t received substantial accolades. In addition to the celebrity testimonials, he’s won lifetime achievement awards from PEN-USA, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Texas Institute of Letters. But it remains a disgrace to American and Angeleno letters that he hasn’t received the Key to the City, White House invitations and all other frivolous pomp that signify authors of his gifts. The reasons for this are obvious.

Over the years, Rechy has endured repeated prejudice and ghettoization, first as a gay writer, then as a Mexican American writer and, lastly, as a West Coast one. As he once famously opined, “It’s been more difficult for me to come out as a Mexican American than come out as gay.” But while most of his peers have died or their work has slipped into the dusty realm of the permanently unread, Rechy remains as vital as ever, proving that it’s never too late for another curtain call.

What were your first memories of Los Angeles?

They were seized away by a cop who interviewed me right away. I had just taken a Greyhound bus to the downtown station and gravitated to Pershing Square, with all the queens and hustlers. I’m sitting there, and here comes — he was either Sergeant Shirley or Sergeant Temple. We called him Shirley Temple, and he’s a character in City of Night. So he points a finger at me:

“You.”

Me?

“Come with me.” My god. Unbelievable. Unbeknownst to most people, they had a police station underneath Pershing Square. And he took me down there. I sat down, and he said, “I know who’s here, I know why they’re there, I know why you were there, and I’m going to be looking for you. Keep out of trouble. I know who you are.” I thought, my god, I have been welcomed … in a sense.

“One of the reasons that I love Los Angeles is all the things that are pointed out as horrible are true and great. All the clichés about Los Angeles are true.”

What was Pershing Square like at the time?

The painter David Hockney attributes City of Night as the reason for him coming out here. He has written about how eager he was to see Pershing Square, but he was staying in Santa Monica. So he takes off on a bicycle from Santa Monica to Pershing Square. I don’t know how he got there. But by the time he arrived, it was already gone, and as though they had exhumed the ground. One time, my Japanese publisher came to talk to me after visiting Pershing Square and said sorrowfully, “But it’s not there. It’s not there. They undid it.” It was once entirely other, but now, no longer. In a sense, it’s very sad that it’s gone, but Times Square is gone too. It’s Disneyland now.

What was your first impression of L.A.?

The palm trees. I love them. They’re so arrogant. They’re literally above everything. In fact, in my book The Miraculous Day of Amalia Gomez, Amalia says, “No tree should look as if it’s ignoring you.” Palm trees are indomitable.

The city was technicolor to me. In my memory, I have the peculiar tendency to remember things in technicolor or black and white. Believe it or not, I never could remember New Orleans in color. If you look at the passages in City of Night, you’ll see a plethora of colors. I was trying to saturate it in color, and it just did not work for New Orleans, so that part is written in black and white. New York is in sepia and a bit of technicolor. But Los Angeles immediately sprang forth in technicolor. It was like the opening of a movie. It was not merely as if I had arrived; it was as if it had arrived in my life.

Did you always feel like an outsider from the literary community in Los Angeles?

Always. There was one brief exception, and I cherish it for what it is. It was my interactions with Christopher Isherwood, who I like very much. What had happened was my story “Mardi Gras” had appeared in the Evergreen Review, and it caused some talk. Then “The Fabulous Wedding of Miss Destiny” appeared. Christopher had told me — this was his way of talking — that he had sent his spies to find me. So where would he send the spies? Downtown to Pershing Square.

Out of nowhere, one of his friends standing in the corner of this bar says, “You’re John.” How did he know? He’d known just from what I’ve written. And he said, “Christopher wants to meet you.” I hadn’t read Christopher but knew who he was. And I quickly tried to brush up because I was going to meet him and a couple of other writers. However, when I turned up, I’m embarrassed to say I made an ass of myself. I’m not very good around writers, unless we’re talking about writing.

They assume a kind of identity, and a certain language and talk. And if you try to match that, you’re really out of it. Now, this was not so with Christopher. I had not yet finished reading The Berlin Stories, but I knew about “I Am a Camera.” And I actually said to him, “After all, don’t you think we are all cameras?”

Later on, I got to know Isherwood very well until the one time where he just wouldn’t leave me alone; he was literally chasing me around the room. We had just had a wonderful conversation about the literature of the time, and I still hadn’t read that many books really, but it was so great. I was sitting there talking to this very famous, admirable writer. A superb stylist, a superb writer. And then all at once, it all crashes.

Do you feel a bias against West Coast writers who played a role in you not receiving the literary acclaim that you might have received had you stayed in New York?

I don’t know. One of the reasons that I love Los Angeles is all the things that are pointed out as horrible are true and great. All the clichés about Los Angeles are true. The excess of cults. Yeah, so what? It brings a strangeness to the city. And the obsession with physicality? I love that. I love the appearance. The beach is beautiful and full of beautiful women and beautiful men. Celebrating the body.

There’s a terrific narcissism that permeates the city. I hate when they describe Trump as a narcissist, because what they really mean is a megalomaniac, and there’s a difference. At its core, narcissism features a love of beauty. For me, it has to have a bit of glamour before it’s true narcissism. Trump? Jesus Christ. Look over there at Marilyn [Monroe], for goodness’ sake. That’s an original lithograph of Marilyn. Narcissism has to have a touch of glamour, a touch of elegance and a touch of arrogance too. And it has to be earned.

You’ve written extensively about the prejudices and stereotypes you faced as a Mexican American writer from El Paso. How do you feel that impact has lingered?

That’s a very, very difficult thing. El Paso was never hard-core, but it was really bad. Because people thought that Mexicans should look one way or talk one way, and I didn’t fit that pattern, I was always an outsider.

It was a pretty nasty sort of thing to be thrown into a situation where I would hear trashy talk about Mexicans. Honestly, this is another thing that’s never truly addressed: the temptation to pass is enormous. I’m sure that it’s the same for Black people, Asians, any minority that can pass. The situation is irrelevant. It pushes you into an area where there is a new kind of bigotry that you’re now exposed to. This hovered over me.

I had a dreadful encounter with some of the Mexican writers when they wouldn’t allow me to be a Mexican in other areas. They wouldn’t have me in the anthology of Chicano writers; the man who compiled it knew my work and refused to include me. It’s a nasty sort of thing.

You’ve repeatedly stressed your aversion to being classified as a Chicano writer and as a gay writer; you just wanted to be seen as a writer.

I will never call myself a queer. That word is one of the things that I detest that has happened, and it’s almost being forced now. For me, you cannot separate that word from the hatred and violence that once accompanied it. When I read it being used in The New York Times, I think, “It’s their word and they can fucking have it all they want.” I will never use “queer.” It’s an ugly word.

I always wrestled against “gay” too. Whoever determines these things always choose such tacky names. We could have gotten a better reclamation. I personally would have chosen ‘Trojans.’ You’ve been on the campus of USC. Have you seen Tommy Trojan? Tommy Trojan is a quintessential gay man. He’s worked out a bit here, he’s flexing his muscles, he has his shield, he has his lovely headpiece. He would be a hit in the gay bars; he’d lead the parade. Do you know how easy it would be to tell your father you’re a Trojan? “Oh … What position do you play?”

“I will never call myself a queer. That word is one of the things that I detest that has happened, and it’s almost being forced now. For me, you cannot separate that word from the hatred and violence that once accompanied it. “

You’ve also blanched at the standard usage of the phrase “sex worker.”

It drives me mad. A sex worker takes the prostitution out of the thing. I remember when a collection of my essays was being published and they referred to me as an “ex-sex worker” and I said, “No way, no way, please. Call me a whore, a prostitute, anything but sex worker.” It disrespects the proud tradition of whoring.

How did being raised in the Catholic Church shape you as a writer?

I was raised a Catholic and have had problems with the Catholic Church dating back to my childhood. When I was about 16, I wrote a poem called “The Crazy Fall of Man.” It’s about how on Judgment Day, God is summoning everybody, and the last witness is Jesus. But they’ve come to accuse him and judge him. So that encapsulates my view of Catholicism.

But it influenced me. Again, the Catholic Church is all technicolor. If you walk into a Catholic church for the first time, you will be dazzled with the colors. The windows, and the beauty of the men and women depicted. The saints are like movie stars. I would go and I would see the Holy Mother in her veil, and she looked like Linda Darnell. And the centurions pushing Jesus? Jesus really knew how to exit.

It wasn’t Socrates with some hemlock. He’s on the cross shirtless with a six-pack.

He has great abdominals and everybody kneeling in front of him, almost naked. I lost a student for saying that one time. She walked out, saying, “I’ve never heard anything like that!” Even now, I feel repelled by the homophobia that still comes through in the church. I knew personally some of the priests, and it was all very hypocritical. But I feel that way about virtually every church.

When you were a young boy, who were the writers that made you want to become one yourself?

I think Faulkner. I actually started to try to read all of him, but it’s impossible. You’d have to dedicate your life; I was just looking through the collection of Faulkner, and there were many things that I didn’t even know he had written — like the short stories contained only in older collections. But he was the big figure for me.

I never met him, but I saw him one time. This was when I was living in New York. I’d been up all night on one side of the city and was cutting across Central Park in the very early morning; I was a little out of my head for a bit. I looked out at the park, and there on a bench in Central Park sat this man, so I actually thought, “I’ve had a delusion.” But I thought, “My god, that’s got to be William Faulkner.” He was reading on the bench, and I read a couple of days later in the paper that he was in town for the opening of Requiem for a Nun. The article said that he liked to go walk in Central Park and read and be quiet. So it really was him.

You maintained a veil of semi-anonymity for many years. Why was that so crucial to you?

Because I wanted to continue [the hustling] life, and it wouldn’t have been possible. If I had been a known writer, I would have been looked at in a different way. I didn’t want anybody to think that I was exploiting them. I was never doing it as research. In fact, it distressed me very much that anyone would think that. I didn’t intend to write about that world until that letter I wrote that eventually became the first parts of City of Night, which drew interest from Grove Press.

Grove asked me if it was part of a book, and I said, “yes, it’s half finished,” because I wanted an advance. But it wasn’t. Those two sections were all that existed.

More than 60 years later, how do you look back on your life at the time and those interactions with the characters depicted in City of Night?

I was a strange little boy who was meeting and discovering things that nobody knew about. It was a world of so much beauty and so much hurt. Miss Destiny, I hurt for her. Years later, I was walking along Hollywood Boulevard, and there comes this voice, “John Rechy, John Rechy!” She stopped traffic and ran into the street. She told me, “I want to thank you, my dear, for making me even more famous.”

A lot of it was fictional, of course. Several years after I saw her in Hollywood, she was interviewed by ONE Magazine and trashed me. It didn’t matter though because she said I was cute. But it’s a very sad sort of thing. At times, I would say that it’s wonderful that every time the book is opened, the characters spring to life again. But that’s not so at all. What springs out is already a character. A representation. And the real people — especially the characters in City of Night — they haunt me. Because… what happened to them?

One of my favorite books is William Styron’s Lie Down in Darkness, and it has a scene where they discuss about a communal cremation of all the homeless people whose bodies go unclaimed, and all of the religious people come and pray for them. I think about how many of my characters from downtown ended up with nobody even claiming their bodies. The ones that were objects of desire when they were young. I escaped it, but only because of my talent.

It does offer a sort of posthumous literary immortality.

Only for the selfish writer who plucked their lives out and made them his own. I feel guilty.

James Baldwin was an early champion of yours, right?

A great one.

How did you come into contact with him?

He was at Dial Press when he read sections of City of Night. So he contacted Grove and wrote to me. He would call me frequently to encourage me and gave really beautiful praise for the book.

How much of the early criticism that you received was merely disguised homophobia?

A lot of it, especially during the first wave of reviews of City of Night. The incredible thing is that some of the worst — including that one from The New York Review of Books — came from gay men. That was the critic who speculated that I might not even exist. Then there were impostors claiming to be me who I read about in columns. I had allegedly been removed from a bar in New York for being obstreperous. It was said that I was a guest of a man on Fire Island, which was absurd because I had never even been to Fire Island.

“The point that I make all the time is we’re the only minority that is born into the opposing camp.”

The worst of all was somebody in Rochester — where I’d never been — who claimed that I had given him VD. I was stunned because I was contacted by the health department back in El Paso. They said that I had to take a test and I said, “No, absolutely not.” They said, “We will send officers to arrest you.” They could actually do that. So I got a lawyer, and they agreed to let me go to my own doctor and be tested. But it’s that sort of thing, in addition to articles where someone claimed that I was a Black jazz pianist from New Orleans who had fled to Paris. I mean really, it was hilarious. Although at the time, it didn’t seem hilarious. It was horrifying.

What was your persona more like on the streets?

I met a few when my editor, Don Allen, had a lunch for me in San Francisco with Michael McClure, Robert Creeley and Allen Ginsberg. Allen was one of the funniest people I ever met. I can’t think of him as the great guru; I cannot. I cannot tell you how hilarious that man was; he had a one-track mind and embarrassed the hell out of me.

I was with a woman friend of mine from Dallas and he was rude and really terrible. He asked me a very blunt question that was none of his business and the whole table reacted. He invited me — he was staying at [Lawrence] Ferlinghetti’s place, so he invited me to have a talk. I didn’t want to go because I didn’t like him like that, but my friend was like, “It’s Allen Ginsberg.” So, I went up with him. I was hardly there for a few seconds when he asked me to take off my clothes. No, I wouldn’t. Then, we got to talk, but then he started singing [William Blake’s] “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” And then [Ginsberg’s longtime partner] Peter Orlovsky called and asked me how many pounds I could lift. I thought it was very funny.

How many pounds could you lift?

At the time, I was pretty good.

What was the allure of hustling for you?

It probably traces back to psychological origins. I loved the adventure and thrill of it all. It was unique, forbidden, and could have a lot of glamour. I probably looked at it like nobody else did, because they were on the streets and I had developed another persona. People who knew me from the streets would not recognize me otherwise.

Did you ever have any interactions with the Beat writers?

For one thing, my talk was very — I’ll use a dated word — hip. Michael [Ewing] and I just finished the screenplay for City of Night, and it was odd to go back; but I tried to use some of those words just to give the flavor of the time. However, there were some that I couldn’t use because nobody would have known them.

You were infamously arrested at Griffith Park and put on trial.

I was arrested three times, but that’s the one that was really terrifying.

What do you remember about that experience?

The real record of it is in This Day’s Death. I actually used the transcript from the trial. And I know this is standard, but the cops lied about the incident throughout.

At the time, among gay people, Griffith Park probably ranked with the Statue of Liberty. It was miles of beautiful green park and miles of sex. And it was private sex because nobody but the gay people knew all the hideaways and coves. It was actually very athletic. You had to be in good shape to climb. What happened was this guy and I were in one of the coves, a block from the main road, completely private. Nothing was happening. Everything was about to happen, and two cops had followed us.

They were so eager to arrest that one came this way and another came this way, and we were charged with what we had intended to do but had not done. So the cop made up this entirely graphic fantasy about what he saw from above, way perched up on a hill.

There were raids happening at the park all the time. I knew that. A friend of mine had told me to watch it and had given me the name of a bondsman, who I ended up using at the time. One cop arrested me, the other cop arrested the other man, and we got taken to the station. I was fearless then. What could they do? I had just started working out and loved my body. When they had me strip in front of everybody in the office, I flexed for them. My inspiration was Susan Hayward in I Want to Live.

I got bailed out right away and got them to bail out the guy I’d been with. That’s when I found out that I was facing five years in prison. Both of us were. Five fucking years in prison. And that’s one of the worst periods of my life because my mother was sick, too. I hired an attorney and told him, “Yes, it was about to happen, but it had not happened.” We hired a videographer to make a movie of where the cops claimed to have situated themselves. I got somebody to draw a map with an X where they had arrested us. I had them film me moving down and staying back there to see whether you could possibly see whether anything had gone down. And it was impossible to see what the cops said they had seen.

The one thing that almost got me fucked — and can you believe my vanity? When they were going to take the movie that day, I didn’t want to take off my shirt. I had worn a tight, flesh-colored shirt, and there I am, on video coming down like it was an audition.

And the judge ordered the jury to go to the scene of the alleged crime like it was a class field trip.

I couldn’t believe it. The goddamn judge wants to go to see where it happened and where we were. At the end of the trial, the district attorney came to us — and by then knows who I am as a writer — and he congratulates me and my attorney. But despite that, they found us guilty, but only of a misdemeanor. I didn’t get jail time.

Looking back on all the homophobia of the time, how did it impact you as a human being?

It’s such nonsense. Such stupidity. But again, I blame the mores of religion. That’s where it comes from. It’s ingrained. As long as the pope says we’re sinners and all that BS, people feel that their hate is legitimized.

A lot of good things happened to get society to this place. There were some very brave people who brought all these cases to light. Michael and I are married now. I don’t like the institution of marriage, but there are benefits that you can get from it, and that was important. A lot of wonderful things have happened over the last quarter-century. But what’s happening now with transgender people is brutal. There are dozens of murders that are happening now in the country, and lawmakers continue to try to legislate against them.

You’ve said before that the media overemphasizes Stonewall as being the central turning point of the gay rights movement. But even before the famous 1967 Black Cat protests in Silver Lake, you’ve said that there were other equally pivotal gay rights demonstrations, specifically the 1958 Cooper Do-nuts Riot.

The overemphasis on Stonewall is bullshit. It’s just that there were a lot of writers there that day to cover it.

There was no riot at Cooper’s. It was actually another donut shop, but at that time, people called every donut shop in the city “Cooper’s” because there were so many. This particular one is gone now. What basically happened was that around 2 AM on Main Street downtown, everyone from the bars would go into the donut shop, and it was a very democratic assembly of drag queens, hustlers and just people staying out late.

The cops regularly went into the donut shop and picked out people to harass. Then they’d parade them out on the street to make an example out of them. Sometimes they’d let them go; other times they’d book them. At the time, it was illegal to be in drag. They had a law against “masquerading.” One night, the cops picked me and a man named Chuck to go outside — and we weren’t handcuffed, but a drunken man started heckling them to let us go. People started making noise and joining in yelling. The next thing you knew, there was a melee, people throwing things at the cops, rocking the cars. It was a beautiful protest against the harassment.

Where do you see the vestiges of the outlaw in today’s society?

I very consciously use that word because “outlaw” has a kind of romance to it. Outlaw is far different from a crook. The stories of the Western outlaws always have a tinge of glamour or legend. The phrase has now become quite generalized. But when I published my book The Sexual Outlaw [in 1977], I was doing a signing in the old Brentano’s store in Westwood. It was very formal then. The salesmen all wore suits; it was very formal. One very bespoke gentleman came in and very intimately whispered to me, “You know we’re all sexual outlaws here.”

How did meeting Michael change your life?

Michael is a miraculous presence in my life. I don’t know what would have become of me without him. I hate this kind of drama, but I never conceived of living this long. I didn’t prepare for it. It was just not a possibility. To age and not be what I was.

I was getting up in years, and it was all becoming very frightening. Michael is so much younger than I am. When I met him he was only 22, but he’s been such a major force in my life. I hate words that carry romantic things, but to feel honest-to-god love, the union, the caring, means an immense amount. It was difficult at first. When he and I first met, I was Johnny Rio [the character from Numbers].

Are you surprised by the tolerance that mostly exists now?

Yes, great things have happened. But my view is that these were things that we should not have had to overcome. The point that I make all the time is we’re the only minority that is born into the opposing camp. Both parents, at least until recently, were straight. So we were born into a whole world of prejudices. Decades, centuries of them. And we’re born out of a union that represents the whole thing. So any gay person born into that camp is already posed in opposition, no matter how wonderful the parents may be. You still have that world, and I’m not in that world.

Beyond the overt prejudice, it led to your writing being pigeonholed into the “gay” subgenre.

You have no idea. When Our Lady of Babylon had just come out, I asked for it in a bookstore in Santa Barbara, and they said, “Oh, it’s downstairs in our gay section.” For one thing, it’s not even a gay book. But when it’s by a gay writer, people will push the books as gay fiction.

What is your new book about?

It’s called Beautiful People at the End of the Line, and it has three epigraphs. The first one is from Bette Davis in Now, Voyager. The second one is from Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon. And the third is, “mumbling, mumbling, shut the fuck up, I’m trying to find something good here.” And that’s Joaquin Phoenix on the set of Batman. I borrow from comic books, the all caps, “WHAM!” and stuff like that.

There are very lyrical passages. It’s really quite a book. It’s about these two young men, they’re not gay — or they say they’re not gay. And there’s a lurid, horrifying, corrupt woman, called the Countess that likes to make amusements for unique people who are comfortable and want to be shocked. She contrives to get a young boy and girl virgin to stage a giant exhibition where they lose their virginity. And it’s about the thought of middle America making two virgins the biggest porn stars in history, because they become idolized across the country.

How far along are you?

A whole first draft is finished. Parts of it occur in Hollywood Forever Cemetery, where two women pretend to be the Lady in Black. There are Hollywood scenes throughout. It’s a unique book; I’ve never done anything like it. It’s finally going all the way with this kind of thing. It’s both a satire and very dark at the same time.

It’s inspired by comic books and celebrity culture. I call it “true fiction.” The Kardashians are characters. There’s a character inspired by [Ohio Republican Congressman] Jim Jordan: a wrestling coach with a peephole into the showers of the young wrestlers.

To me, true fiction is where constantly the reader is made aware that he or she is reading. It’s all an artificial structure, and you are to respect it as such. I love to write a passage, a narrative, and then say, “That’s not good; it didn’t happen like that,” and then write another one that takes its place and leave it up to the reader to decide which is the real truth.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Stepping out in the morning and the whole world applauding.

What is your greatest fear?

Growing old, as I am.

What is the trait you most deplore in others?

Academic pomposity. Overt fakery. I mean overt because you can be a very genuine fake. Pomposity.

Which living person do you most admire?

Michael.

What is your greatest extravagance?

Myself.

What do you find is the most overrated virtue?

Humility. Humility is a detriment, a bad condition, and the most arrogant stance that you can take.

When and where were you your happiest?

When my books come out, sure. But when Michael and I were traveling in Europe once, and we had a communist lady as our guide. She took us to the Sistine Chapel and got us a pass so we just glided through. And she had already paid all the guards off. And we’re sitting in the Sistine Chapel looking up. It was beautiful. A poor woman came up and tried to sit with us, and the communist guide says, “You can’t sit here! We paid for this!” And it just illuminated the whole thing: the Sistine Chapel, Michael and the communist lady. It was a telling scene.

What talent would you most like to have?

I have all the ones I want.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Making it through life while living creatively.

What is your most treasured possession?

My body.

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

People who have utter contempt for other people’s suffering.

Who are your favorite writers?

Dead or alive? Look, I have to go with the clichés: Joyce at his best, and Proust, especially because I would be chastised by my gay brothers, especially at Yale, if I left him out.

What’s your favorite Joyce?

Portrait of the Artist. Ask me who I think is the most underrated writer in the world? Shakespeare, because you cannot overpraise him.

Who’s your favorite character of fiction?

Scarlett O’Hara and Molly Bloom.

Which historical figure do you most admire?

Spartacus and Marie Antoinette. As a kid, I was writing a book that included her. I found out all kinds of fascinating things. She had quite a life.

Why do you think she was so historically maligned?

They were bad times, and they had to have a lot of villains. She was not a villain. She did not say, “Let them eat cake” — yet that remains.

Do you have a motto?

Live.

How would you like to be remembered?

As a great writer.