For a distinctly reverent gathering, there’s a lot of vomiting. I can’t see the person gagging on the other side of the candlelit room, but I hear them churning up something from deep inside themselves, and whatever that is is hitting the bottom of a plastic bucket with a hard splash. To my left, a middle-aged woman sobs into her hands, while a white-haired old man on my right laughs hysterically. “I get it!” he yells into the rafters of the cavernous space. “I see it all so clearly now!”

I look up to the ceiling and see nothing, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t anything there. In the middle of this room on the semi-rural outskirts of Los Angeles County, a trio of musicians dressed entirely in white perform a ballad with acoustic guitar, hand drums and lyrics about the glory of the wind.

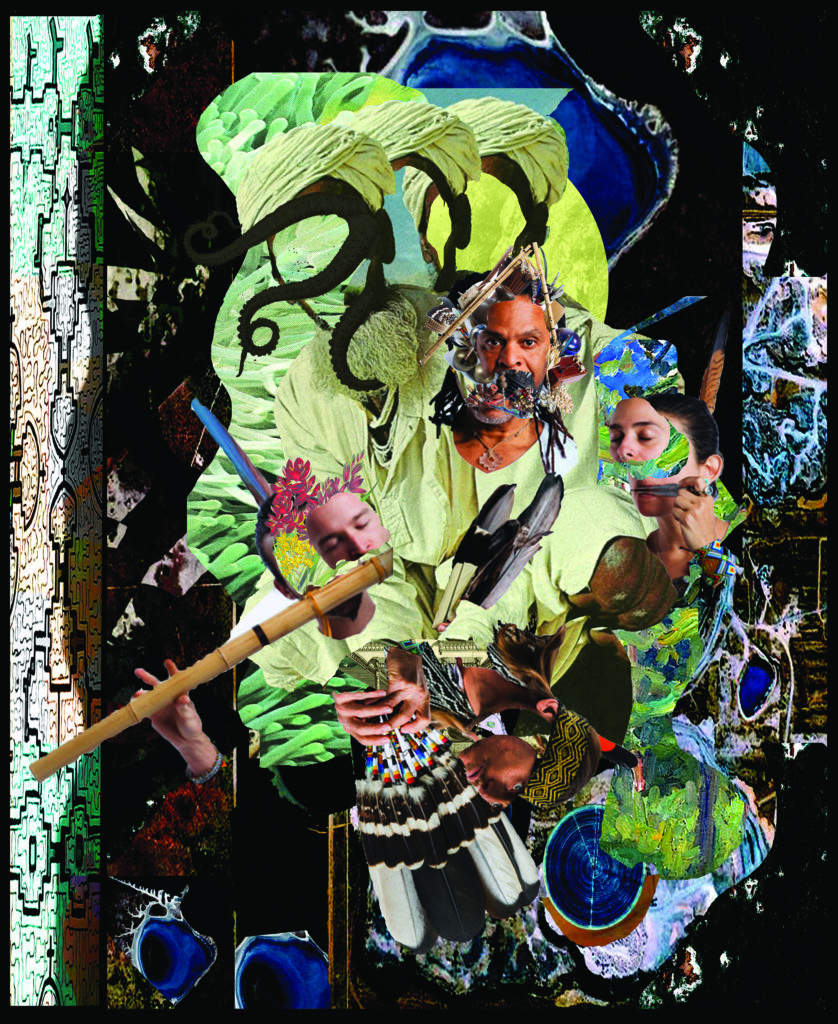

As the song crescendos, a thin woman stands and spins, her hands raised over her head and her skirt floating into a kaleidoscopic whirl. When the song is over, no one claps. There are rules here, and not clapping is one of them. Anyone who’s sat in an ayahuasca ceremony will affirm that the music really does move you to tears, to laughter, to understanding, to catharsis. Thus comes Birds in Paradise, the debut album from Los Angeles collective Bird Tribe, a sprawling group of musicians and artists who have for years served as the house band for L.A.’s progressive spiritual scene. They’ve played tea ceremonies, cacao ceremonies and art galleries in Venice.

You’ll catch them at sustainability talks out in Topanga, hosting a discussion by Brazilian tribal elders at an old church in East Hollywood, playing a late-night show at Lightning in a Bottle. In a city where connection is famously difficult, their mission is to foster meaningful interconnectedness between each other, with nature and with indigenous wisdom.

They feel that if there is hope for humanity, it’s in these activities.

While my Midwestern upbringing instilled in me a skepticism for false gods, flashy gurus and overt absurdity, the ceremony and the songs played during it are honest and powerful, having facilitated some of the more profound moments of my life. I can hum any one of them and remember what it was like to finally grieve the deaths of my grandparents, to forgive myself for all the moments I had failed myself and others, to cry until I couldn’t cry anymore, and to realize Magical Mystery Tour is gospel and all you really need is love. Thousands of people in Los Angeles can, more or less, say the same.

Birds in Paradise is the sonic component of this mission.

With it, Bird Tribe intends to share the depth of meaning and sense of connection inherent to ayahuasca with as many people as possible.

You might have the same gut reaction as many people have to the idea of going to Burning Man (in short, “no fucking way”). But take part in any of Bird Tribe’s events and you’ll likely be won over by their kindness, authenticity, diversity and depth of talent.

“Anybody that does this type of work absolutely knows that it’s ceremonial music,” says Tony Moss, the dreadlocked and quietly wise de facto leader of Bird Tribe. “But to other people, it might just sound like The Lion King.”

Music has always been part of the ayahuasca tradition, which originated in the Amazon Basin thousands of years ago and has found strong footing in Southern California, a region long receptive to all flavors of spiritual mysticism. Made of a vine and leaf boiled into a thick tea, this “plant medicine” is intended to induce a heart-and-mind-opening journey. It’s a bit like acid, and also kind of like church. While the local scene exists largely underground — ayahuasca is illegal in the United States — dozens of ceremonies may happen on any given weekend in the greater L.A. area.

In the Amazon, where tens of thousands of people descend each year to participate in ayahuasca tourism, songs range from simple melodies sung by a solo vocalist, to complex, almost alien song structures performed by a half-dozen signers. Considered the engine that moves each ceremony forward, the songs are traditionally called icaros, with each icaro believed to carry a particular type of healing — a song for a broken heart, for strength, for forgiveness, for peace. In certain traditions, songs are believed to carry the medicinal properties of the particular plant referenced in the lyrics. These songs are sung by curanderos and curanderas, healers who lead the ceremony, with melodies and styles passed down over centuries. But as the global revival of indigenous practices spreads ancient knowledge to new demographics and parts of the world, working in tandem with the so-called “psychedelic renaissance,” the music of Bird Tribe — original, contemporary, pop-oriented and produced using the same methods as most anything on the radio — is adapting tradition as much as it’s extending it. Not everyone approves.

“Understandably, many people who study shamanism and other traditional indigenous ceremony practices want to preserve tradition,” says Moss, who has studied plant medicines and shamanism since first drinking ayahuasca almost a quarter-century ago. Raised between Northern and Southern California, Moss grew up singing in church and is the son of singer Rejoyce Moss, who, along with two of her sisters, formed ’60s gospel act The Stovall Sisters. The trio sang backup for a long list of icons including Ray Charles, Etta James and Al Green and themselves pushed the boundaries of what traditional religious music could be with their eponymous 1970 gospel/R&B crossover album.

It’s a bit like acid, and also kind of like church. While the local scene exists largely underground — ayahuasca is illegal in the United States — dozens of ceremonies may happen on any given weekend in the greater L.A. area.

“There’s a concern about appropriation and misuse of traditional ceremony practice,” says Moss. “But traditions can and do evolve — and, more importantly, adapt to the culture and times.” On Birds in Paradise, the adaptation is distinctly Southern Californian. Moss considers the album a manifestation of L.A. culture in the same way Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours captured the crystal visions of 1970s SoCal. The album is an exquisitely pretty extension of the canyon music lineage of Joni Mitchell and Neil Young, with Bird Tribe offering the same low-key, nature-based spirituality of their counterculture predecessors. There are dreamy homages to the vitality of water dressed up in moody strings. “Kalyana” is a sing-along about the wind and would be a Top 40 hit had Ed Sheeran written it. “Pink Dolphins” honors the indigenous tribes who live along the rivers of the Amazon. “Sundance Song” represents the Lakota music often played in ceremony. Considered sacred and rarely performed in public, it’s shared on the album with permission.

Bird Tribe includes Moss (who’s worked in musical theater for over a decade and has released music under his own name), renowned frame drum player and singer Miranda Rondeau, Diana Carr (with a voice that rivals Feist), multi-instrumentalists Sunny Solwind, Tëté Bero, Shireen Jarrahian, David Daniel Brown and an extended network of guest players. Songs are sung in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Lakota, “spirit language” (channeled words that have meaning but don’t directly correlate to any known language) and Shipibo, the language of the Peruvian tribe most associated with the development of ayahuasca.

The Shipibo are among the Amazonian tribes thanked in the liner notes for the “friendship, knowledge and healing modalities that have blessed the lives of so many.” While mainstream media coverage of ayahuasca has largely obsessed on the wildness of the experience and the handful of deaths that have occurred at retreats (none actually from ingesting ayahuasca), what’s been less reported on are the millions of people who have achieved clarity, inspiration, hope, purpose and physical and emotional wellness through their work with the plant. Birds in Paradise aims to expand this influence. The album is structured to mimic a ceremony, with the same invocations, themes, moods and pacing. While it could easily fall in the world music genre, Moss calls Birds in Paradise “medicine music” — music created from, or intended for, ceremony that exists to support intentions of peace, love and healing. Those who have sat in ceremony — teachers, doctors, lawyers, movie stars and studio executives among them — will attest that it works in whatever way one needs it to, that the medicine is clever this way.

“Pop music will typically try to be as neutral as possible, as universal as possible,” Moss says. “An artist doing medicine music is unconcerned with that, because your whole point is to be direct about what you’re saying, whether it’s forgiveness or having gratitude.”

Of course, many songs are sincere, and all forms of music from Biggie to Backstreet Boys can inspire devotion.

But these songs and others like them are played explicitly to facilitate catharsis, spiritual connectedness and good feelings, rather than to validate the performer or entertain the audience. It’s the reason no one claps. This isn’t Coachella.

But considering L.A. is a world capital of the music industry, it’s logical that music in the ayahuasca scene would be elevated. Gifted musicians have naturally gravitated to the spiritual scene, with many of them finding a place to share their talents without the requisite pressures of achieving fame. Their work serves a higher purpose here: healing you, and through you, healing the world.

“Even when I’m stuck in traffic and in moments that can be challenging and jaded, listening to this music creates more space inside myself for creativity and play and activity and giving,” says Jarrahian, who played flute, handpan, jaw harp and more on the album. “Even my dog sings along with me.”

While Moss says there’s no way they’ll recoup the tens of thousands they spent on recording, it was more important to see where they could take each track, and how far beyond L.A.’s relatively insular spiritual community they can now share it. “Amazonia” will be remixed by a collection of DJs popular in the transformational festival scene, and several music videos will be released over the coming months. The potential, they believe, is tremendous. Anyone who listens might become that white-haired old man, laughing at the ceiling, seeing it all so clearly now.