One evening in March 2020, John Collinson was washing dishes when he glanced up out his kitchen window and noticed something different about the grassy hillside behind his house. Bright orange flags waved atop brand new surveying stakes delineating two vacant parcels on the steep south flank of one of Highland Park’s last remaining open spaces, Poppy Peak. For Collinson, a 20-year resident of the neighborhood, this raised the alarm.

“My initial reaction was panic, really,” he recounts. “This land I thought would in perpetuity never be developed was suddenly not being conserved.” The hillside had changed before; it had once been covered in native sages and oaks, with a blanket of California poppies each spring to rival the famous blooms of the Antelope Valley. When the previous landowner refused to clear brush for fire abatement in the mid-‘90s, the City of Los Angeles bulldozed the entire hillside, destroying the rich ecosystem. Nonetheless, the weedy field at the top of the hill remained one of the few places in this fast-changing part of the city that hadn’t been built upon.

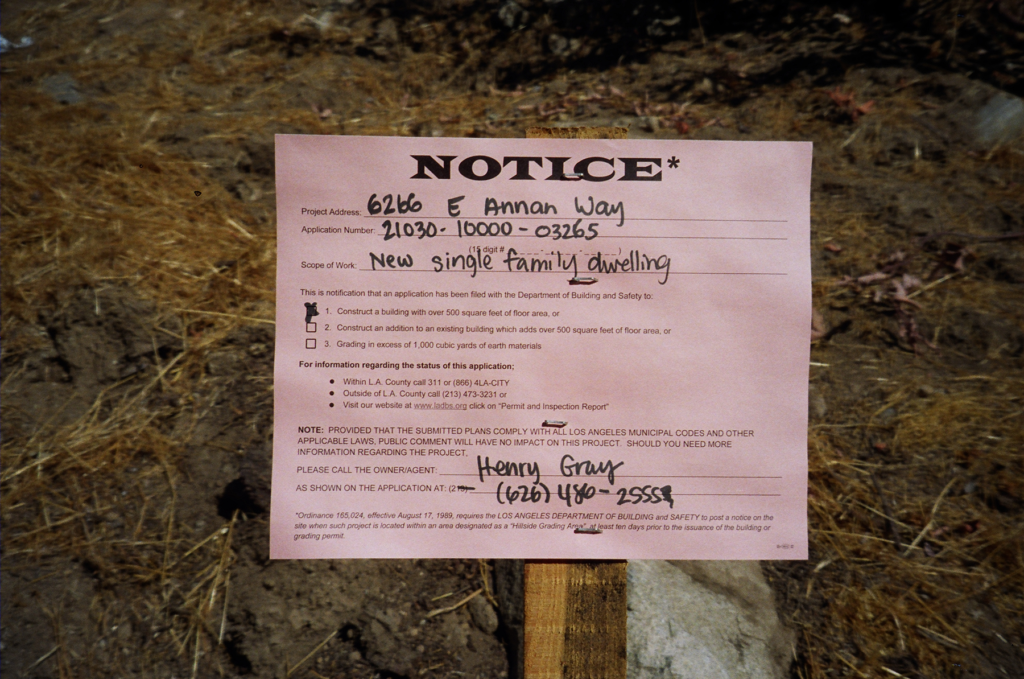

Neighbors on Annan Way, several streets over, shared Collinson’s concern when construction began on two large, modern luxury houses on the north side of the hill. They discovered a developer, Ahmad Abghari, owned 16 parcels on the hilltop and had already submitted permits to construct a third home. Collinson and his neighbors on the streets adjacent to the hillside responded by forming Save Poppy Peak: a coalition of community members working with elected officials and other stakeholders to protect the area’s last hillside from residential development and give one of Los Angeles’s oldest neighborhoods much needed access to green space. He says, “What some people call ‘sprawl’ is actually a result of a lack of planning over centuries, and unfortunately it seems this has become the precedent for future development.”

Versions of this story are playing out across nearly all of the remaining open green spaces in Northeast Los Angeles, raising an important question: As the supply of undeveloped land in L.A. becomes scarcer than ever, what is to be done with it?

It’s no secret Los Angeles has a serious housing crisis — a reality developers often cite when trying to justify new development on fast-disappearing open lands — but it doesn’t take an expert to see that multi-million dollar hillside mansions are hardly the solution. Collinson says, “We really need to debunk this idea that hillside development is going to solve low-income and middle-income housing shortages. You could argue all this development is just making housing less affordable for everyone.” Roy Payan, a community activist in Northeast L.A., elaborates, “It’s like trying to fit a square peg in a round hole.”

Abghari hasn’t commented on his plans for the remaining seven acres, either to the community or in response to inquiries from theLAnd, but residents fear he will simply continue to build homes “by right” and recently retained a land use attorney to appeal any new construction permits on these grounds. This loophole in the Los Angeles Municipal Code allows landowners to avoid a slew of government and environmental reviews by constructing one house on a property at a time. Someone looking to turn Poppy Peak into a 16-home luxury hillside development would likely be denied permits for the full project due to the vast ecological and neighborhood impacts, but a developer constructing homes by right, one by one, can bypass the entire process.

An assortment of amendments to the Los Angeles Municipal Code exist to curb this kind of development, most notably the Northeast Hillside Ordinance. But Payan, who co-authored the Northeast Hillside Ordinance, notes that “the mechanisms simply are not in place to enforce [these laws],” and the burden to respond to violations falls on nearby residents. During construction of the two homes on Annan Way, for instance, the developer damaged the root system of a mature oak tree. Oak trees are protected under the Los Angeles Municipal Code, but the punishment for damaging one is almost nonexistent.

“There’s a lot of equity in a mature oak tree that’s 60 years old,” Collinson observes. “We need these trees for urban sustainability, to mitigate pollution and increasing temperatures, and here they are tearing them down to build houses.”

Save Poppy Peak believes the decision of what to do with the land should ultimately rest in the hands of those who have a stake in this neighborhood already. And while there are differing views as to what the community needs — some longtime neighbors welcome the addition of high-end housing after decades of local disinvestment — many, including Save Poppy Peak, would like to see the land used as a park.

Los Angeles has a serious park equity crisis to match its challenges with housing — especially in Northeast L.A. Recommendations for public health established by the Trust for Public Land suggest communities should aim for all people to be within a 10 minute walk of a park or open space. The next closest park for residents around Poppy Peak is double that. Meanwhile, new research by the Prevention Institute shows that increasing park acreage in park-poor areas of L.A. County has the potential to increase life expectancy in those areas by up to 164,700 years across the population.

“That means my kids growing up will have a shorter life expectancy than somebody living on the West Side,” Payan notes. “How unfair is that to us? That’s inequity.”

“Our challenge with Poppy Peak, and all the other neighborhood hillside groups, is to elevate the issue and take claim of our neighborhoods and urban habitats which support our quality of life here, and our overall community health.”

John Collinson

Save Poppy Peak, however, believes the open space could do even more for the community. They are looking to leaders like biologist Matt Teutimez, a first-nation Kizh Gabrieleño and active member of the Tribal Advisory Council for California’s Environmental Protection Agency, to develop a new model for community parks. “If we’re looking at Poppy Peak as a park,” Teutimez says, “the vision is that it could be an example of the land showing us how to care for the land and an example of how the land wants to bring us together as a community.”

Indigenous stewardship practices such as clipping back native sage and elderberry are beneficial not only to the health of those plants but to that of the community, providing teas, herbs, food, and medicines while simultaneously reducing the fuel load for wildfires. “If you’re going to create a park and bring back native species to that park, then bring back the tradition of using those native species,” Teutimez explains.

The result might be something that functions as part-community garden, part-native landscape, part-indigenous classroom, and part-science experiment — a park that actually engages the neighborhood around it. “We always want to incorporate education in, too, because why are we restoring it?” Teutimez adds. “For us, it’s not just for the ecological value, we want it to have a community value, to draw people to it, because that’s what the land wants to do, bring us together.”

The most immediate question facing Save Poppy Peak, though, is how to save the land at all. The developer purchased all sixteen parcels atop Poppy Peak in 2017 for a mere $1,070,000. Save Poppy Peak recognizes the price has likely increased in the interim years and is actively seeking out grants, donations, and other public funds to facilitate the purchase of the land. As their petition gains momentum, they grow more confident they will be able to raise the funds needed to purchase the land if they can convince the developer to sell — but that’s a big if. Abghari applied for three more construction permits in August.

Nonetheless, the group is seeing progress in the form of a growing grassroots movement. Leaders from a variety of neighborhood organizations dedicated to protecting similarly at-risk parcels of land across Northeast Los Angeles are creating NELASOL (Northeast Los Angeles Save Our Lands) to combat hillside development in park-poor communities at a legislative level. “Our challenge with Poppy Peak, and all the other neighborhood hillside groups, is to elevate the issue and take claim of our neighborhoods and urban habitats which support our quality of life here, and our overall community health,” Collinson explains. These spaces have the potential to represent a new form of urban decision-making and of land conservation.

“Poppy Peak is a great candidate for this sort of model,” Teutimez says. “The community of microbes which supported a diverse range of life are still there below the surface in the soil. As soon as you remove invasive species and revegetate with native species, those natives will take off like crazy. If we get involved up at Poppy Peak we’ll allow the landscape to take care of the community.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect the correct spelling of Abghari’s name and developments following his application for additional construction permits in August.

Additional Northeast L.A. Hillside Organizations and Campaigns

Save Our Eagle Rock Hillside

Save El Sereno’s Hills / Coyotl + Macehualli

Save Paradise Hill

Save Walnut Canyon

Free Flat Top

Heroes of Elephant Hill