I. First Day Out

On his first day out of jail, Fredid Toledo went home to his mother, took the best shower of his life, and shaved for the first time in two and a half years.

“When you’re in jail you only get three-minute showers,” he remembers, chuckling.

It was 2014. Smooth faced and clean, the 18-year-old called up some friends he hadn’t seen since his arrest for armed robbery. These were close buddies, not related to the gang life he was trying to leave behind. Things were going to be different this time around.

When his buddy dropped him off at home that night near MacArthur Park, he sped away instantly. Toledo scanned the deserted streets uneasily. Anyone in a gang knew not to drive away before making sure your homie was safe inside.

On the balcony next to his mother’s apartment, a group of men were drinking and playing loud music. A cold certainty seized him: 18th Street gang members. The building his mom had moved into on Alvarado and 3rd was in the heart of their territory. Toledo was part of Witmer Street gang, their direct rivals.

“They knew I’d gotten out,” says Toledo. “Word spreads like wildfire man.”

They were waiting for him. Toledo sprinted down Alvarado. At the liquor store on the corner, another gangbanger was buying more beer for the guys upstairs. He chased after Toledo, brandishing a gun.

“I’m like, man — I’m not gonna survive.”

At the corner of MacArthur Park, he banged on a bus to let him in. The driver kept the doors closed. Toledo risked a desperate look backwards. The man was nearly on him; he raised his gun. Toledo banged and banged on the bus. Miraculously, the doors opened.

“The driver is like: ‘What the fuck do you want?’” Toledo says, grinning at the memory. “I’m about to get smoked, close the doors!”

The 18th Street gangster strolled up to the bus just as the doors closed, gun in hand. A wide smirk covered his face.

“You got lucky,” he told Toledo.

That night, Toledo slept at a friend’s house in Boyle Heights. Home was not an option anymore.

“That was a wake-up call that I needed to change my life around, live by a certain set of rules. Or else…,” he shakes his head grimly. “You know.”

Sitting in his light-filled office, it is difficult to believe that this is the same man who once shot and was shot at by other human beings. For the last two years, the now-27 year old Toledo has worked at Homies Unidos, first as an administrative assistant and now as youth development coordinator.

Homies Unidos – known simply as ‘Homies’ – has a cramped office on Beverly and Alvarado. It was founded in El Salvador in 1996, by ex-MS-13 gang member Alex Sanchez, who relocated it a year later to L.A., to help former gang members get their lives back on track and prevent young kids from joining. There’s nine members on staff, all from the Westlake/Pico-Union area where they work. It’s a heavily immigrant, primarily Salvadoran and Mexican neighborhood that took shape in the ‘80s and ‘90s, as millions fled U.S.-funded civil wars in Central America.

Under the jurisdiction of the LAPD Rampart Division, it is also one of the most heavily policed neighborhoods in the country. In 1998, only a year after Homies started work in Westlake, the division’s anti-gang CRASH unit was the center of one of the largest corruption and police misconduct scandals in history.

Long before he ever joined a gang, Toledo learned to be afraid of cops. Running to make it home before curfew one night, a police officer pulled up to him.

“Where you from? You got any tattoos?”

When Toledo refused to be searched, he says the officer became aggressive.

“Don’t make me take you to the cut and beat you up,” he told the 14-year-old Toledo. The cut is slang for someplace out of sight.

Police have harassed Toledo like this more times than he can remember. Inside the police, there are forces pushing for change.

“People fail to realize how much the LAPD has evolved,” Deputy Chief of the LAPD Emada Tingirides says.

She pioneered a program to restore trust between the police and high crime neighborhoods and is now the Commanding Officer of the newly formed Community Safety Partnership Bureau (CSPB). She is also the highest-ranking black woman in the LAPD.

“I think we’re one of the most progressive law enforcement agencies in the country, and that’s because of our failures in our past. We have come a long way since 1992.”

But CSP efforts are concentrated in the Watts neighborhood of South L.A. In Westlake/Pico-Union, there is still no CSP site. In their absence, it falls to people like Toledo and community organizations like Homies Unidos to help the neighborhood heal.

In name, Homies is a gang intervention non-profit. In real life it’s a catch-all for the community’s needs. Gang members find it nearly impossible to stop gangbanging, so Homies pays for reintegration courses and tattoo removals. The neighbors are going hungry because of low pay and meager government assistance, so Homies runs food distributions at their office. Young men suffer from police harassment and punitively long prison sentences, so Homies organizes grass-roots advocacy groups to lobby for the rights of the incarcerated in Sacramento.

At Homies, Toledo shepherds the younger generation, guiding kids referred by school administrators, parents, or friends. On any given day he goes around in the Homies van picking up the kids at local high schools and middle schools and bringing them back to the office for group sessions he designs himself.

“There was a time when I almost went through with killing myself,” says Martin Lopez, one of Toledo’s former mentees. “Fredid picked me up that night.”

Lopez was 15 when his mother called Homies, concerned about her son’s depression and worried he would join a gang. He started coming by Homies to attend Toledo’s sessions, where the kids crowd into a tight circle of chairs in the tiny, windowless front hall. Little by little, passing around a colorful wooden talking-stick, Toledo got Lopez talking about his insecurities. Soon, he had him helping pass out food to the families around Westlake.

“He would always walk with his head down, didn’t meet your eye,” Toledo says of Lopez. “Now he’s got a sparkle in his eye, you know? He walks chest-out.”

Lopez is 17 now. He credits Toledo with helping him discover that he enjoys helping others.

“Fredid is a humble person,” says Alex Sanchez. The Homies founder is a big, laughing bowling ball of a man. Around Westlake, he’s something of a local legend. Everyone seems to know him and have his number saved. “It took a while to bring Fredid around. But he doesn’t realize how much he does to support our youth and people in need.”

Toledo’s objective is clear: to make sure none of the kids he mentors ever follow down the path he did. But Homies’ youth programs rely on grants from benevolent foundations. And as of today, the funds are running dangerously low.

II. Roots and Initiations

Born in 1995, Fredid Toledo grew up only a couple blocks away from where he was nearly killed 18 years later. He was always skinny, earning him the nickname Flaco. Today he’s soft-spoken, with dark, intelligent eyes. He speaks in spare, trim sentences, with the occasional spark of humor flashing across his face.

His mother, Julia Calderon, paid a coyote to come to L.A. from Guerrero, Mexico, when she was 17 years old. When his little sister Jenifer was born, their father left the family.

“He was a machista,” Toledo says. “He firmly believed that he didn’t create any women.”

Calderon was left to care for their three children — 5-year-old Fredid, 4-year-old Gerardo, and the newborn Jenifer — alone. She worked as a bartender and kitchen prep, making just enough to pay the bills and put food on the table. Since she was always working, the kids spent most of their time with babysitters. These were older women who often physically abused them.

“They’d hit us, whip us,” Toledo says. “One babysitter threw the TV remote at Gerardo and gave him a scar. He still has it to this day.”

Life in the poor, largely immigrant neighborhoods west of Downtown L.A. was rough. Alvarado Street, the main north-south artery, is a drab succession of gas stations, fast food chains, and liquor stores. On most days, the sun casts a blinding white glare on the treeless streets. With no shade, the heat is ruthless. The Salvadoran family restaurants and occasional market stalls sprout up happily, almost impossibly, like flowers between cracks of cement.

By the time he got to John Leichty Middle School, Toledo was an easy target for gang recruiters. Gangs were part of the fabric of life: kids threw up their set, graffiti announced their presence, and most people had friends or relatives who banged. To this day, Toledo still knows whose territory he’s walking in.

Smoking weed with a buddy one day by a liquor store, he was approached by a couple of older guys. They asked him and his friend where they lived and offered to buy them beer. Then they started asking if they were “part of a neighborhood.”

“We kept saying no, but they wouldn’t stop insisting,” Toledo says.

Eventually, he gave in. The older guys shoved him to the ground and beat him up for 13 seconds — the traditional initiation ceremony for new gang members. Toledo was 12 years old. His initiators were 17 or 18. He was officially a Witmer Street gangster.

Witmer is one of many street gangs in Westlake. North to south their patch of territory stretches between Wilshire and Olympic Boulevard. To the West the line is South Union Avenue. The Harbor Freeway and Bixel Street provide natural borders to the East. Like most Mexican-American gangs, they often add the number 13 to their name to indicate their allegiance to the Mexican mafia.

“In the prison system we would unite with other gangs with the 13,” Toledo explains. “But in the streets the majority of gangs have issues regardless.”

When he got home the night of his initiation with a bruised face and a dislocated arm, he told his mom that he’d been jumped. She believed him until someone sent her a video of the initiation. By then it was too late.

“As soon as you get in, [the gang] asks where you live, your phone number,” Toledo says. “It’s constant monitoring. Where you at? Why haven’t you come to the neighborhood? We’re going to come find you.”

At first, Toledo stayed out of fear. Then he says he stayed because he enjoyed it: the gang filled many of the holes in his life. It provided him with strong father figures (“I was the youngest — most of them were 17 to 25”), an outlet for his trauma (“from my own abuse, I only knew how to have fun by hurting others”), and a source of money (“I dealt mostly weed and crack”).

At a very fundamental level, it gave him a sense of belonging. They all had nicknames — there was Player, Grim, and Wicked. They had clear enemies: MS13, 18th Street, Rockwood Street, Orphans 13. It gave him protection and street cred.

At 13 years old, kicking it with one of his Witmer Street buddies, they got a call that a rival gang was driving a truck through their territory.

“We ran to the building to get guns, rifles, a sombrero,” he says. “Then we posted up on the corner of the school. We knew what truck we were looking for.”

The second the truck came into view, the older guys opened fire. Toledo heard the crack of the windshield and the screech of the wheels as they fled. They’d failed to kill the driver.

“Them being grown men they went back to the house, they changed clothes, they peed on their hands,” says Toledo, alluding to the belief that urine makes gunshot residue undetectable. “I was shocked. I wasn’t yet fully corrupted.”

When he got back to school the next week, though, Toledo saw he’d earned a reputation. His siblings started to pick up on it too; he wore baggier clothes, the Nike Cortez’s. Gerardo wanted to join Witmer Street and started drawing Ws everywhere.

“I beat him up, smacked him,” says Toledo. “I knew it was a bad thing, and I didn’t want him to be a part of it.”

“I guess the way I expressed it wasn’t the healthiest,” he adds with a wry smile. “All it did was push them away to rival territories.”

Gerardo started hanging out with Rockwood Street and Lincoln Heights gangbangers. Jenifer started seeing 18th Street guys. The siblings, who had been close as kids, grew distant and suspicious of one another.

On most days, of course, gang life was non-violent. It consisted of drinking and getting high with the homies at different houses in the neighborhood. What little money they had came from selling weed and crack.

But when the violence flared up, it returned with a vengeance. As he got older it got worse. To pay the weekly dues, he started robbing — mostly drunk men walking late at night.

“You choke them out. Instill fear in them. Then it’s easy.”

When he was 15, the older guys decided it was time for him to become un hombre. They gave him a 20-gauge shotgun and went to reclaim Orphans 13 territory. Orphans was a “one-building gang” that had carved out an enclave inside Witmer territory at the apartments on Green Ave and 8th Street. The Witmer guys were “tagging” in an alley — spray painting their gang symbols — when one of their rivals pulled up.

“That’s when they tell me ‘Shoot him,’” Toledo says. “I’m already pointing the gun at the guy, I’m debating it.”

He let rip, the shotgun recoil slamming his shoulder. He missed.

“They keep yelling ‘Shoot him! Shoot him!’ But that’s when I see his wife is in the passenger seat and his three kids in the back seat. I froze. That’s what stopped me from killing him.”

When they got back to the neighborhood, he got another 13-second beatdown for hesitating to shoot.

Things got worse from there. The year of his arrest, Toledo was walking on 3rd and Loma with his girlfriend in Rockwood Street territory. He was bald-headed and tattooed, a proud Witmer Street member. Sure enough, a clique of Rockwoods pulled up.

“I just took my arm off my girl and told her ‘Walk the other way,’” Toledo remembers. “‘Pretend you don’t know me.’”

Toledo ran fast, but there was nowhere to escape. Desperate, he scrambled over a high gate into an apartment complex, carried by a surge of adrenalin.

The Rockwood gangsters patrolled the perimeter, waiting for him to make a run for it. They kept yelling: “You’re not gonna make it outta here alive.”

“I was looking at my phone like, ‘Who do I call?’ None of my homies wanted to pull through,” says Toledo. “Then I remembered: Alex Sanchez.”

When Toledo called, all Sanchez said was: “I’ll be right there.”

“So, Alex pulls up with four vans,” says Toledo. “All of these guys looking like cholos. I mean these are OG veteranos.”

Sanchez had pulled up with the big guns. These were former gang members who had been there in the worst of the worst of the ‘80s. Some of them had seen over 30 years of prison time. None of the Rockwood Street gangsters said anything as Toledo walked calmly into Sanchez’s arms.

“When you come into the neighborhood with that type of manpower, nobody gonna fuck with you,” says Toledo. “That was super powerful. Who does that for me?”

Sanchez did not stop there. Right after rescuing him, he took Toledo to a movie premiere.

As we drive through Rockwood Street gang territory on a blustery Friday afternoon, Toledo says that he still does not walk around those streets.

“It’s too dangerous,” he says. “An older cat could recognize me, might remember me.”

“It took a while to bring Fredid around. But he doesn’t realize how much he does to support our youth and people in need.”

Alex Sanchez

Years after leaving gangbanging behind, the invisible lines demarcating territories are still as vivid and real in his mind as the day he quit. It is hard to heal from trauma when the names of the streets are heavy with gang connotations.

Sanchez saved him that day, but he could not pull him from the spiraling violence. Soon after, Toledo witnessed an older homie crack a pregnant girl over the head with a hammer, just because she was from a rival neighborhood. He dropped out of school and moved into one of the gang houses. His mother had moved to the building on Alvarado and 3rd — 18th Street territory — and it was a death sentence for him to live there.

One night out robbing, he slipped up and made a rookie mistake.

“When you rob people, you want to make sure you take everything. Every last cent,” Toledo says. “Even if you take their phone, they might use those coins on a payphone.”

That night he was sloppy. One of his victims called the police and they arrested him and took him to the Central Juvenile Hall. The worst part was losing his Colt 45. He had bought it for $900 from a homie, with money from robbing and selling crack. It was his biggest purchase.

The charge was armed robbery. He was sentenced to two years in Camp Afflerbaugh, a juvenile detention center in La Verne, CA, at the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains. He was 16 years old.

III. In Jail

If two guys were going to fight they sat down in the showers, locked legs with one another, and went at it until someone was either bleeding badly or about to pass out. It was the best way for the guards not to notice. Of course, fights happened outside the showers too.

“Fights occurred all day, every day,” Toledo says. “You got down by your bed, you got down in the showers, you got down by the kitchen. Anywhere.”

Toledo’s first fight was in the bathroom. He won that one.

“When you go in there you’re repping a certain set. You can’t sleep safe.”

Camp Afflerbaugh is divided into four dorms: Charlie, Bravo, Delta, and Alpha. Each one houses about 30 inmates, all of them under 18 years of age. All the inmates can socialize during the day at lunch and recess, but at night they have to go back and sleep in their assigned dorm.

“Once I was sleeping and this guy comes over from another section. He’d filled his sock up with rocks during rec[ess]. He ran across the hall and started cracking the guy next to me sleeping.”

The guards came over and tackled the aggressor. This was the way of things: the guards turned a blind eye until it was too late. Then the inmates involved were rounded up and had their sentences extended. If an inmate turned eighteen, they were transferred to an adult prison.

Life at the camp passed like this, in a soul-crushing succession of bland meals, bloody fights, and interrupted sleep.

John Mathews, Senior Justice Deputy at the Office of Los Angeles County Supervisor Holly Mitchell, is working to improve the treatment that incarcerated youth receive. The County Board of Supervisors approved a motion in March to explore moving youth out of juvenile halls and into camps.

“Barry J. [Nidorf Juvenile Hall] is notorious, the youth that come out of there have nothing good to say,” Mathews says.

Toledo himself bounced around juvenile halls, including Barry J., before going to Camp Afflerbaugh.

“That’s because it looks really carceral. They don’t have enough programming and education.”

When I tell Mathews that conditions did not improve much for Toledo between the juvenile halls and Camp Afflerbaugh, he assents.

“The facility is just the first step, absolutely,” he says. “It’s about staffing these camps with community-based organizations who are credible messengers, who can come into the camps and halls and relate to the youth.”

For all two years of his sentence, Toledo’s mother visited him every weekend. She had no car and barely any money, but every Sunday she took the bus up to La Verne.

“Not once did she not show up,” Toledo’s eyes glimmer with sadness. “She’d fold up a twenty, super small, and they wouldn’t see it when she got searched.”

With the money his mom snuck in for him, he could bribe the guards for some McDonalds, pizza, or chicken noodle soup.

“When you’re in jail, even the guards are crooked,” Toledo says, shaking his head.

Toledo was a secretive, furtive kid. It’s not that he behaved well in jail. It’s that he never got caught for the bad stuff. Sometimes Gerardo brought him a Hot Cheetos bag he’d emptied out and taped back up with weed. Other times it was a Snickers bar, drained of caramel and stuffed with about seven grams

“Weed that would’ve sold for $70 outside, I could make $300 from inside,” Toledo says.

He was wily. His sentence never got extended. When his two years were up, his mom brought him back to the neighborhood, in desperate need of a shave and a good shower.

IV. Mother and Son

After a few weeks of living in Boyle Heights with a buddy, Toledo decided he was going to live with his mother, regardless of the rival gangs. He told everyone he came across that he wasn’t a part of that life anymore. When his old homies came around to beat him up, he hid from them.

For a time, it seemed like he might just turn things around. He got a job as kitchen prep at El Pollo Loco and another at Chuck E. Cheese and started earning an honest wage. The 18th Street gangsters left him alone. His old homies stopped bothering him.

Then one day, two years after getting out of Camp Afflerbaugh, it all came crashing down. His buddy had called him with a strange story: he’d been drinking beers with a random guy in a parking lot. The man had been drunk and apparently offered him his car for free. Did he want to go take it out for a spin?

Driving the car, the cops pulled them over for a cracked windshield. When the officer ran the plates, it came up that Toledo was driving a stolen car. His buddy had been duped. The original thief had wanted to get it off his hands to hide his trail.

Back in County Jail, Toledo dialed his mom.

“It was $500 bail. I had the money. I just needed her to come in and sign the papers,” he says. “It wasn’t even about being in jail. I just had to go back to my job so I wouldn’t get fired.”

“These are some of the things that gangbanging brings. It ruins the relationship you have with your siblings, your parents.”

Fredid Toledo

His mom hung up on him. Her patience with him had reached its end. Toledo got another friend of his to come and post the bail instead.

From that day on, the relationship between him and his mother was broken. Toledo now had to pay $500 a month for rent. Neither Gerardo nor Jenifer had to pay anything.

“At family dinners she wouldn’t put my plate out, to make me feel like I didn’t belong,” Toledo says, in a hushed tone. “She locked up the fridge. She started complaining when I used the kitchen.”

The memories of his mother are more raw, more painful to summon than any of the many times he nearly died while gangbanging.

“When the day came, she had no idea I was moving out,” Toledo says. “I asked her: ‘how much do I owe you for last month’s rent?’

She said: “Nothing. Just leave my house.”

Since that day six years ago, Toledo has not spoken to his mom. He lives only a couple blocks away from her, though he doubts she even knows this.

“Even though my brother also did bad things, I was always the black sheep,” he says with a sigh. “She hurt me a lot too, you know?”

Toledo accepts the full weight of his responsibility.

“These are some of the things that gangbanging brings. It ruins the relationship you have with your siblings, your parents.”

At 21, Toledo moved into a small place of his own. In a short time, he had lost the protective net of both Witmer Street and his family. He was, for all intents and purposes, alone in the world.

At his hearing for driving a stolen car, Toledo was handed 400 hours of community service. It did not matter that the rightful owners of the car testified that Toledo was not the thief.

As he scanned the list of organizations where he could volunteer, a name caught his eye: Homies Unidos. He remembered how years ago, before he went to jail for the robbery, Alex Sanchez had saved his life.

Toledo looked up. “I’ll choose Homies,” he said.

V. Redemption

On a recent Friday afternoon, Toledo invites me to sit in one of the sessions. They come into the office after school, laughing and gossiping. Before sitting down in the circle of chairs, they pillage the office kitchen for Hot Pockets and potato chips.

There are five girls that day, most of them 12-15 years old. Then there’s Obed, a 13-year-old boy with an impish grin that seems to be perennially plastered across his face.

Obed was referred to Homies by his school after he brought a BB gun into class one day. His middle school is in MS13 territory, but he lives on 18th Street turf. Even though he’s not part of any gang, everyone at his school assumes he is.

“It’s hard when you’re constantly being identified as one,” says Obed.

Toledo sees himself in Obed: the same age when he joined a gang, suffering from the same structural pressures. These are cycles of poverty (the amount of ramen, taquitos, and junk food the kids eat at Homies indicates this is a main source of food), violence (a 13-year-old feels compelled to bring a BB gun to middle school for protection), and bad policing (the first question law enforcement ask Obed is always: “What gang are you in?”).

During his sessions, Toledo guides the kids gently around difficult subjects, getting them to open up to each other about their fears and hopes.

“If you were to cry for no reason, your parents would give you a reason to cry,” says Eliza, 14. Her parents are both still active gang members. She hopes to choose a different path, to make her grandmother proud.

Other girls speak of constantly moving from evictions or of being single mothers. All of them agree on one thing: coming to Homies is much better than sitting at home. These kids are the product of broken families, typically absent fathers and abusive mothers. Toledo listens intently, gathering their worries into himself.

There is something incredibly stirring in witnessing his quiet enthusiasm as he works with the kids. Toledo holds the passionate zeal of a convert, intent on spreading the word that change is possible, despite everything.

“Now that I have two daughters, I try to empower and connect with them,” he says. “They love me. I love them. I’m trying not to repeat what happened when I was young. I give them affection and love.”

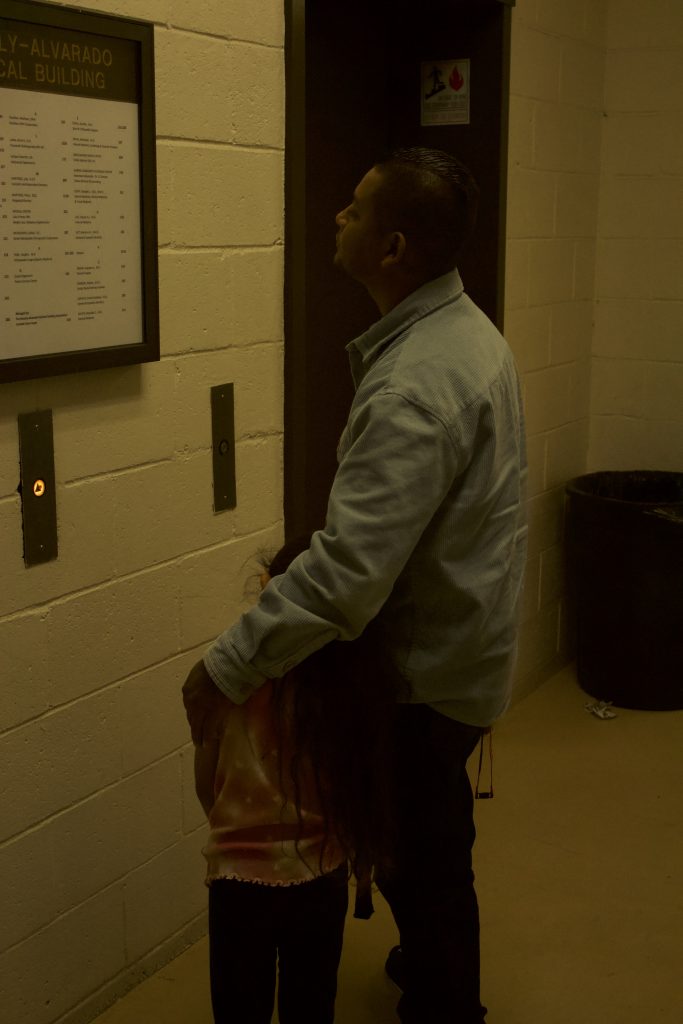

On another Friday afternoon, I hop in for a ride with Toledo and we go pick up his youngest daughter, Skylah, from Equitas Academy Elementary. She is a spritely, talkative little child, with all the world-weary opinions and sass of a girl three times her age.

“Why don’t you take me out?” she says. “Dads are supposed to take their daughters out.”

Toledo shakes his head, smiling, and swings into a McDonald’s drive thru.

“I try to give her healthy foods, you know?” Toledo says, justifying himself. “She doesn’t eat candy bars when she comes to my place.”

“Yes I do!” Skylah chirps up. “Sometimes I do.”

Skylah’s mother, Reina Sanchez, calls to check up. Toledo’s relationship with her is strained at times, but they co-parent well. The girls sleep at their respective mother’s homes but spend a lot of time together in their dad’s company.

Almost immediately after, Toledo gets a call from another former gang member, who wants to know if he qualifies for money from the Rodriguez settlement. The class action lawsuit successfully sued the City of Los Angeles in 2011 for gang injunctions that enforced unconstitutional curfews on over 6,000 Angelenos.

As Toledo explains the paperwork to him, we pass his mom’s building on Alvarado, the liquor store, and the corner of MacArthur Park where he nearly got killed. By Lafayette Park, Toledo hangs up and chuckles.

“I got jumped there when I was 19,” he says. “A group of MS-13 guys kicked me in the face.”

In the backseat, Skylah plays with her Sonic the Hedgehog Happy Meal box, giggling every time I point the camera at her. When I ask him if his daughters ever wonder about his past, Toledo shakes his head.

“I feel like it’s never going to be brought up,” he says. “I don’t want them to even know what gangbanging is. That starts with me — I’m very involved in their lives. I know when parents aren’t, that’s when bad decisions happen.”

He says the macho culture in Hispanic communities is still a huge obstacle.

“A lot of fathers don’t tell their sons ‘I love you,’” he says. “If I cried, my mom would whip me and tell me ‘Boys don’t cry.’ She would put rice on the floor and make me kneel on it.”

Alex Sanchez has told him to speak to his mother. Will he ever be ready to reach out to her again?

Toledo hesitates. He wants to say yes, but chuckles instead. “I don’t know. Maybe someday.”

Ultimately, Toledo is grateful he was one of the few that got out of the neighborhood alive. Wicked, one of the older guys who initiated him, is dead now. Grim is doing prison time.

As a counselor to the kids, Toledo tries his best to shepherd them away from that life. It’s a job full of rewards when he sees them growing in confidence and strengthening their resolve to make something out of their lives.

It’s also a job that couples with tragedy. Wilbert, one of his mentees, was 18 when he was shot in the head at a park last year. Toledo had been guiding Wilbert, an active Diamond Street gang member, because he was in and out of jail and wanted to stay out of the hood.

“Wilbert would often call me in the middle of night because he was stranded in the wrong territory,” Toledo says. “Doing this type of work you have to answer calls at all hours.”

Wilbert regularly volunteered at food distributions with Homies, and Toledo helped him get his California ID. This can be hard for guys who are confined in the hood, either because they don’t have transportation or because the government office is in rival territory.

“When he passed away we helped with a car wash for him,” Toledo says. “Homies Unidos also donated money to his sister and mother.”

Toledo has the silent resolve of a man who has been through Hell and is intent on never going back. What’s more: he means to save the kids from his neighborhood from ever going there at all. The forces he faces are far vaster than him: dysfunctional families, easy gun access, hunger, deportations, a cruel, inhumane policing and justice system… But every day he shows up to Homies, or picks up desperate calls in the middle of the night, because it is the right thing – the only thing – he can do.

“Once upon a time it was my ambition to make a name for myself with the clique in the neighborhood,” Toledo says. “Now it’s to make a name for myself helping others.”

But Toledo’s work at Homies is imperiled. Organizations like Ready to Rise, Liberty Hill Foundation, and the Global Fund for Children provide a series of grants to fund the youth program. But at the end of the most recent grant cycle, money is running low — and there’s no certainty the grants will be renewed. Toledo has already seen his sessions reduced from five to three days a week. To lose the resources to help youth, having come so far, saddens him immensely.

“To [the kids] it would feel like another person has given up on them,” he says. “Youth need guidance from mentors that can relate. Or else, the streets will get to work.”

On a recent Saturday, Toledo gathers the kids on 8th and Witmer. Over the next ten Saturdays they’ll paint a giant mural on the outside wall of Ministerio Jesus El Salvador del Mundo. Each kid will receive a $500 stipend for the work. It’s the sort of cash Homies might not have for much longer.

“I’m giving back to the community I once destroyed. There’s no breaks in this type of work.”

These days he loves to hike, fish with a buddy, or chill out with a few beers over Santa Monica pier. Looking back over his life, Toledo waxes philosophical.

“I’m not religious, but I try to do good things, to replace all the bad things that I’ve done.”

In his own quiet, diligent way, Toledo radiates compassion. In his role as moral and spiritual leader of the youth he works with, the gangbanger once known as Flaco has seen himself reborn.

“I have a purpose now in my life, and it’s to guide these kids so that they don’t feel alone.”