Listen to a playlist featuring 224 songs from this list.

Before you can rank the “greatest L.A. albums,” you’re forced to confront the ontological question of “what makes an L.A. album?” As a music industry capitol and locus for transplants, you can make the case that practically anything qualifies. From the iconic Sunset Sound (Led Zeppelin, Prince, and the Rolling Stones), to Electro-Vox Studios (Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra), to the old RCA headquarters, L.A. has long been a premier recording option for visiting musicians hoping to soak up sunshine and waves, high-caliber narcotics, and all the other indulgences that define the Hollywood cliché.

But just being within the city limits doesn’t remotely get you close to the essence. A classic L.A. album has to reflect something of the city itself: its shifty moods and pulmonary rhythms, its eccentric cultural pockets and beautiful but slightly cracked reflection. The very sound itself has to be “L.A.” So even though Sam Cooke and Bobby Womack created their most iconic compositions while living and recording here, their vision was unquestionably one of Midwestern and Southern soul. Motown decamped to L.A. in the early ’70s which led to many of its most immortal late-period releases being laid down in Hollywood, but no matter where Marvin Gaye recorded, he’ll always belong to Washington D.C. and Detroit. You can even make the case that Thriller counts, considering Michael Jackson had lived in L.A. for a decade-plus, it was produced by Quincy Jones, and featured locally based session musicians; but it was clearly an international pop blockbuster, not something that the city could rightfully claim.

When it comes to jazz, the inverse is true. South L.A. nurtured some of the world’s supreme visionaries — Charlie Mingus, Pharoah Sanders, Don Cherry, Eric Dolphy, and Ornette Coleman — but they all were forced to move to New York to prosper. Their classics were almost all universally recorded there, and bear little evidence of the cool jazz that L.A. once incubated (although we included Coleman’s debut, cut before he headed east).

The point that most frequently bears repeating is that this is all totally arbitrary and subjective. We heavily slanted this list towards art cradled in the turf between Long Beach and Topanga (no, the O.C. doesn’t count): the formative music that shaped regional scenes, blasted out of local clubs and cars, the sounds that are indigenous to L.A. But there are always exceptions. Charlie Parker was from Kansas City and made his name in New York, but his fleeting sojourn in L.A. (and the mental hospital in Camarillo) irrevocably influenced both genre and region with some of the most remarkable modal levitations ever recorded. The early Beastie Boys are inextricable from New York, but Check Your Head marked a transformative shift, unmistakably shaped by their new home, and one that kickstarted a generation of rock and rap hybridization.

We aspired towards inclusion but not at the expense of impairing a specific vision. Our sensibilities were primarily shaped by punk, jazz, psychedelic rock, and hip-hop, so the list reflects that. Of course, some essential stuff got cut for space. We promise that you’ll survive. All apologies to James Taylor and Carole King, but, honestly, no apologies to James Taylor and Carol King. This is theLAnd, not Soft Rock and Crystals Quarterly. There are no Eagles albums on here because The Dude was right (we know the truth). If you don’t like it, make your own list, or take the culinary advice that Snoop gave at the start of “Lodi Dodi.” But as he continued on that masterpiece from Eastside Long Beach by way of Slick Rick: “for those who with [us], sing that shit… it goes a little something like this.” — Jeff Weiss

To Live and Die in L.A. (#110-#31)

110. Linda Perhacs — Parallelograms [Kapp, 1970]

109. Charles Wright & the Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band — Express Yourself [Warner Bros., 1970]

108. Freddie Gibbs & Madlib — Piñata [Madlib Invazion, 2014]

107. Bonnie Raitt — Takin’ My Time [Warner Bros., 1973]

106. Jackson Browne — The Pretender [Asylum, 1976]

105. The Muffs — Blonder and Blonder [Reprise, 1995]

104. Jurassic 5 — Jurassic 5 [Rumble, 1997]

103. Chicano Batman — Cycles of Existential Rhyme [El Relleno, 2014]

102. The Seeds — The Seeds [GNP Crescendo, 1966]

101. The Gerald Wilson Orchestra — Live and Swinging [Pacific Jazz, 1967]

100. Angry Samoans — Back From Samoa [Bad Trip, 1982]

99. Suicidal Tendencies — Suicidal Tendencies [Frontier, 1983]

98. Harry Nilsson — Nilsson Sings Newman [RCA Victor, 1970]

97. Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti — Before Today [4AD, 2010]

96. Chalino Sánchez — El Pela Vacas [Musart, 1992]

95. Rain Parade — Emergency Third Rail Power Trip [Restless, 1983]

94. The Mamas and the Papas — If You Can Believe Your Eyes and Ears [Dunhill, 1966]

93. Vince Staples — Summertime ‘06 [ARTium/Def Jam, 2015]

92. Above the Law — Livin’ Like Hustlers [Ruthless, 1990]

91. Ornette Coleman — Something Else!!!! [Contemporary, 1958]

90. The Game — The Documentary [Aftermath/Interscope, 2005]

89. Earl Sweatshirt — I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside [Tan Cressida/Columbia, 2015]

88. Nosaj Thing — Drift [Alpha Pup, 2009]

87. Open Mike Eagle — Dark Comedy [Mello Music Group, 2014]

86. Project Blowed — Project Blowed [Project Blowed, 1994]

85. Blu — NoYork! [New World Color, 2011]

84. Madlib — Madlib Medicine Show (Vol. 1-13) [Madlib Invazion, 2010]

83. Patrice Rushen — Straight From the Heart [Elektra, 1982]

82. No Age — Nouns [Sub Pop, 2008]

81. DāM-FunK — Toeachizown [Stones Throw, 2009]

80. David Axelrod — Song of Innocence [Capitol, 1968]

79. Tim Buckley — Starsailor [Straight, 1970]

78. Taj Mahal — Taj Mahal [Columbia, 1968]

77. Spirit — Spirit [Ode, 1968]

76. Shalamar — Three For Love [SOLAR, 1980]

75. The Egyptian Lover — On the Nile [Egyptian Empire, 1984]

74. L7 — Bricks Are Heavy [Slash, 1992]

73. Emmylou Harris — Pieces of the Sky [Reprise, 1975]

72. The Runaways — The Runaways [Mercury, 1976]

71. Kamasi Washington — The Epic [Brainfeeder, 2015]

70. The D.O.C. — No One Can Do It Better [Ruthless, 1989]

69. Ice-T — Power [Sire, 1988]

68. The Watts Prophets — Rappin’ Black in A White World [Ala, 1971]

67. Tyler, the Creator — Igor [Columbia, 2019]

66. Thundercat — Drunk [Brainfeeder, 2017]

65. The Germs — (GI) [Slash, 1979]

64. The Flying Burrito Brothers — The Gilded Palace of Sin [A&M, 1969]

63. Horace Tapscott — The Giant Is Awakened [Flying Dutchman, 1969]

62. 03 Greedo — Purple Summer [Golden Grenade Empire, 2016]

61. Warren G — Regulate… G Funk Era [Violator/Rush Associated Labels, 2014]

60. The Byrds — Sweetheart of the Rodeo [Columbia, 1968]

59. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young — Déjà Vu [Atlantic, 1970]

58. Steely Dan — Gaucho [MCA, 1980]

57. Brenton Wood — Oogum Boogum [Double Shot, 1967]

56. War — The World is a Ghetto [United Artists, 1972]

55. Dennis Wilson — Pacific Ocean Blue [Caribou, 1977]

54. Descendants — Milo Goes to College [New Alliance, 1982]

53. Nipsey Hussle — Victory Lap [All Money In/Atlantic, 2018]

52. Beck — Odelay [DGC, 1996]

51. Hole — Celebrity Skin [DGC, 1998]

50. Ritchie Valens — Ritchie Valens [Del-Fi, 1959]

49. Tha Dogg Pound — Dogg Food [Death Row/Interscope, 1995]

48. Los Lobos — Kiko [Slash/Warner Bros., 1992]

47. Van Halen — I [Warner Bros. 1978]

46. Shuggie Otis — Inspiration Information [Epic, 1974]

45. Tom Petty — Full Moon Fever [MCA, 1989]

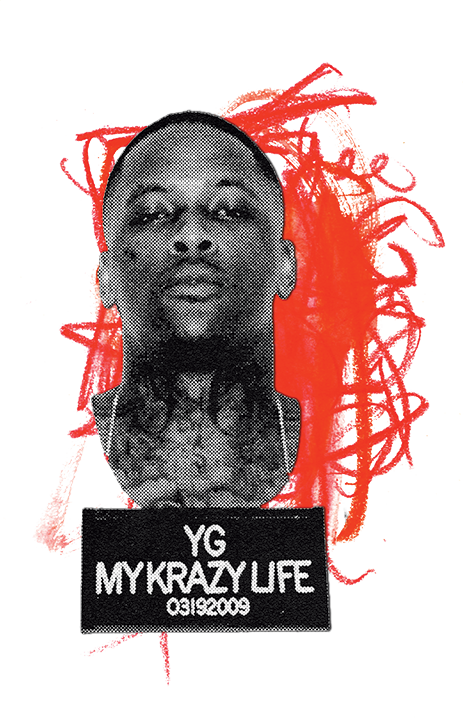

44. YG — My Krazy Life [CTE/Def Jam, 2014]

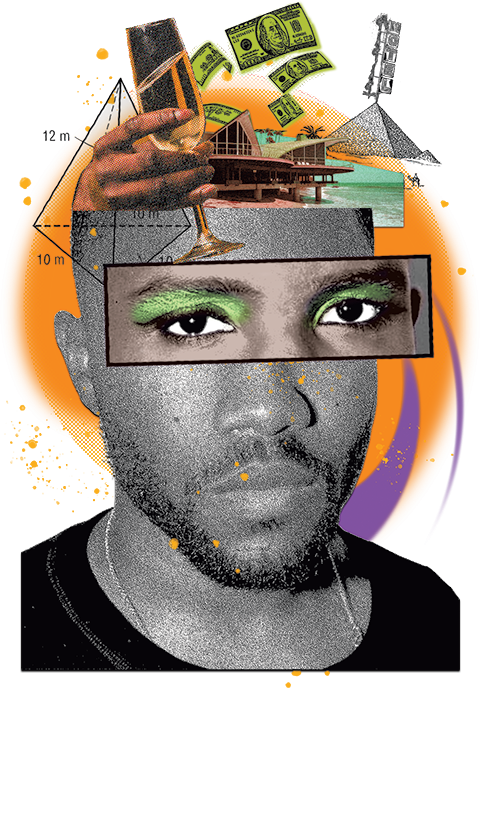

43. Frank Ocean — Channel Orange [Def Jam, 2012]

42. Rage Against the Machine — Rage Against the Machine [Epic, 1992]

41. Warren Zevon — Excitable Boy [Asylum, 1978]

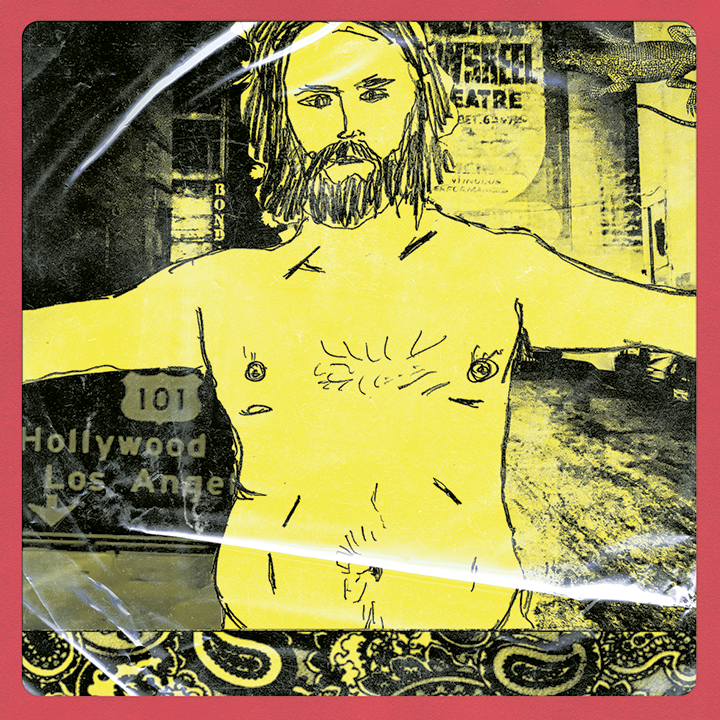

40. Jane’s Addiction — Nothing’s Shocking [Warner Bros., 1988]

39. Sublime — Sublime [MCA, 1996]

38. Cypress Hill — Black Sunday [Ruffhouse/Columbia, 1993]

37. Mazzy Star — So Tonight That I Might See [Capitol, 1993]

36. Joni Mitchell — Court and Spark [Asylum, 1974]

35. Neil Young — After the Gold Rush [Reprise, 1970]

34. Captain Beefheart — Safe as Milk [Buddah, 1967]

33. The Beastie Boys — Check Your Head [Capitol, 1992]

32. The Doors — The Doors [Elektra, 1967]

31. Dr Dre — 2001 [Aftermath/Interscope, 1999]

How the West was Won (#30 – #11)

30. Red Hot Chili Peppers — Blood Sugar Sex Magik [Warner Bros., 1991]

It’s easy to clown on Blood Sugar Sex Magik a full three decades after its release. For one thing, there’s Red Hot Chili Peppers frontman Anthony Kiedis, whose frenetic vocals encompass frat boy chants and nu metal raps, funkadelic harmonizing, and twangy, dopesick croons. Then, there are the lyrics — Seussian rhymes infused with schoolyard sexual innuendo — oozing lust for everything from peace and racial justice to DTF lady cops, and getting so high you actually might die.

But if you can get over the initial eye-rolling that comes with lyrics like “every woman has a piece of Aphrodite,” you’ll simply give in to the madness — no, the sheer exuberance — of the thrashing bass, screeching guitar, feverish drums, and yes, even the pseudo-rapping. Perhaps you might stomp, sway, and throw your arms overhead in ways embarrassingly evocative of the ’90s; but you’ll also feel enormously free and maybe even a little ecstatic.

Blood Sugar Sex Magik, the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ fifth studio album and the one that catapulted them to fame, is both staggeringly sincere and refreshingly silly. Recorded in producer Rick Rubin’s allegedly haunted Laurel Canyon mansion, the 17-track opus is relentlessly experimental, criss-crossing genres while pogoing between extreme sentimentality and orgiastic absurdity. It is the sound of intoxicating testosterone, overwhelming horniness, and in the case of its biggest hit, “Under the Bridge,” devastating loneliness and scathing remorse. Not unlike Los Angeles itself — the city we live in, the city of angels — Blood Sugar Sex Magik is imbued with manic duality, brimming with pleasure, sorrow and possibility. — Jenn Swann

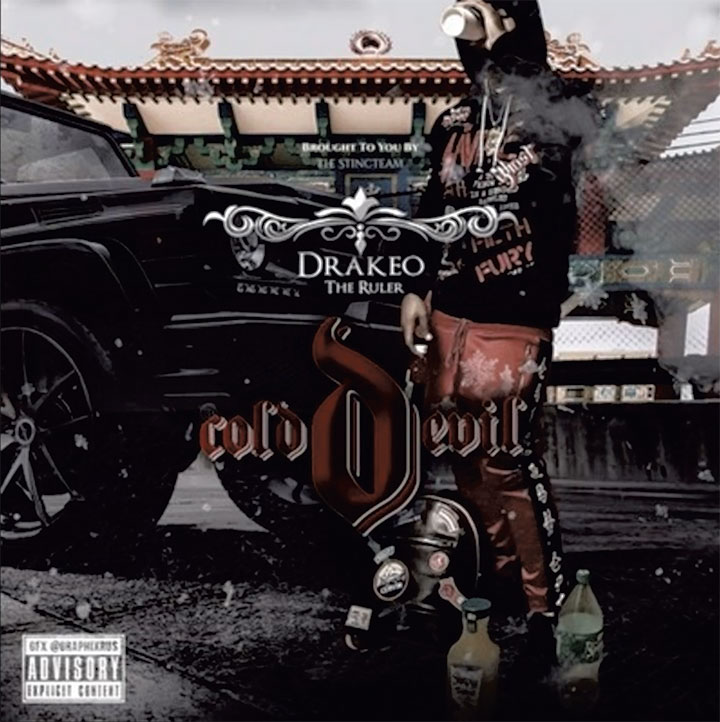

29. Drakeo The Ruler — Cold Devil [Stinc Team, 2017]

Within hours of mudwalking out of his cell at downtown’s Men’s Central Jail, Drakeo was already in the booth, minutes from his 24th birthday, sprinkling blue-faced Benjamin Franklins on the floor. Written behind bars, South Central’s Ruler recorded Cold Devil within a week of his release for felony gun possession charges in the late fall of 2017. Before he had a chance to promote it, he was back in MCJ’s dungeons, potentially facing the death penalty. During that brief window, these satanic verses revolutionized the slang, cadences, and slap of West Coast rap (and inspired a fatwa or two).

A street-certified classic from neighborhood sets to Stockton, the only people who memorized it with greater accuracy were in the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department and District Attorney’s office, the latter of which soon indicted him on highly dubious murder charges. For the next three years, he languished in solitary confinement, fighting a cartoonishly monstrous prosecution that criminalized his lyrics, image, and crew. Understood in that context, Cold Devil isn’t just an album: it’s a manifesto of brazen defiance and contemptuous taunts, a sawed-off declaration of war against a system and other sections who would stop at nothing to destroy him.

Off music alone, it remains a 5 mic masterpiece, the most inventive reimagination of L.A. gangsta rap since Snoop wore Cool Water Cologne. Drakeo conjures a codeine fog of cryptic lingo: flu flamming and Pippy Longstocking’s, big bank uchies and Mei Ling-financed shopping trips to Neiman-Marcus. A labyrinth of crashed foreign cars and ransacked homes, crime scene tape and blood-drenched Maison sneakers, hysterical contempt and lethal subliminals. The Volvo in the back of your Snapchat can never be unseen.

His flow scrapes like a winding snake, slithering through unseen tunnels of the beat — intricate slurs that inspired a generation of people’s champs from San Diego to Sacramento. The production ushered in the era of nervous music, a more sinister evolution from ratchet’s pool party minimalism. Within 18 months of its release, Greedo, Drakeo, and the entire Stinc Team were incarcerated; Shoreline Mafia had already experienced a meteoric rise and fall. But Cold Devil captures the zenith of this swift renaissance — one that brilliantly created the future of West Coast rap with a radical new language, but remained plagued by the same stresses and evils of the past. — Jeff Weiss

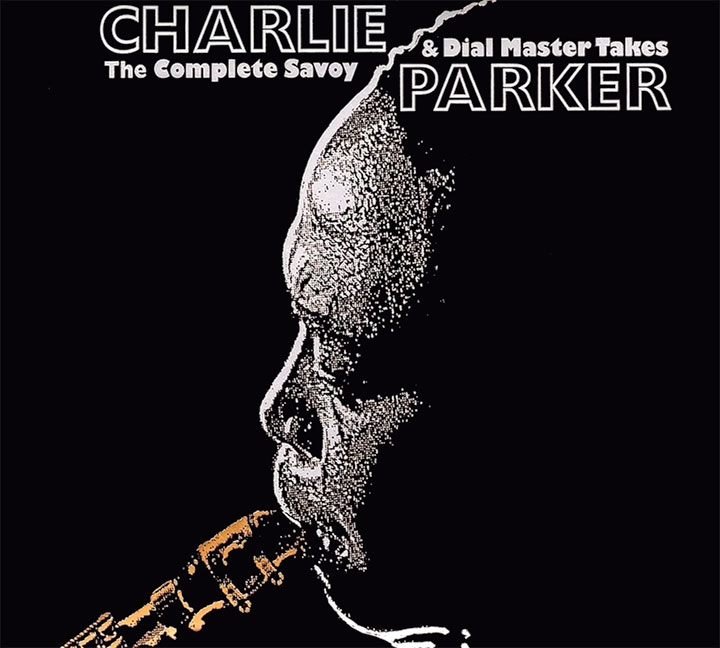

28. Charlie Parker — Dial Sessions, Volume 1/1946 [Dial, 1946-1947]

Sometime after high school, polio took star athlete Emery Byrd’s ability to walk. By the mid-‘40s, he was operating a shoeshine stand on Central Avenue that sold bootleg jazz records and heroin. To the neighborhood, he was known as Moose the Mooche, as immortalized by bebop saxophonist Charlie Parker, who relied on Byrd to supply him during his raucous Southern California stay.

Parker arrived in Hollywood from New York in December of 1945, only 25 but with a strong reputation for musical innovation and self-destruction. When his band flew home in February, Parker was a no-show. He wouldn’t return to the East Coast for nearly two years.

Ross Russell, a Hollywood record shop owner, started the Dial Records label in 1946 with the sole intent of recording Parker while he was living in LA. “Moose the Mooche” was an emblem of Parker’s unmistakable bebop prose. It was recorded at his first Dial session in March of 1946. Not long after, Parker signed over half his Dial royalties to Byrd who ultimately failed at keeping Parker supplied. By the summer, Byrd was in San Quentin Prison and Parker was headed for a six-month stay at Camarillo State Mental Hospital.

Parker’s tumultuous tenure on the West Coast became a watershed moment for a local jazz scene that had been thriving for decades. His presence gave credence to a generation of local boppers that included future Dial recording artists Dexter Gordon, Hampton Hawes and Charles Mingus. These California sessions show Parker at the peak of his brilliance and struggles. Seventy-five years later, Parker’s message is still winning converts and the musicians of Los Angeles are still grappling with his sermons; the Dial sessions remain an undeniable cornerstone of that fundamentalism. — Sean J. O’Connell

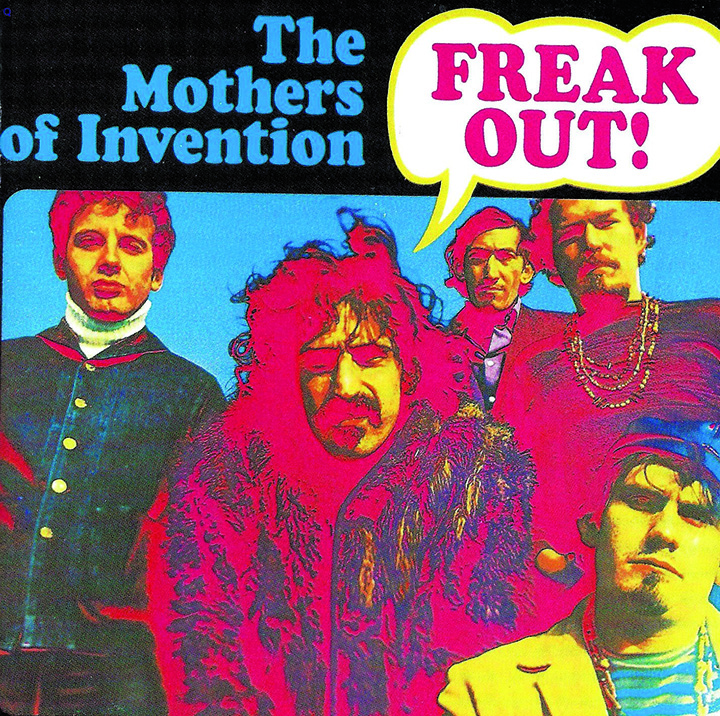

27. The Mothers of Invention — Freak Out! [Verve, 1966]

Forget the conformist hippies of San Francisco and picture instead the showboating freaks of Los Angeles, who hung out at Canter’s and Ben Frank’s because with their long hair they couldn’t get in anywhere else, who showed up to parties in tights and capes, and had nicknames like Captain Fuck. Zappa winkingly assured the nervous listeners in Kansas that people would never start freaking out there, but meanwhile the freaks were busy humming and strumming and providing a weird percussion backdrop for side four of the double LP, the first in the history of rock music, or whatever you want to call this bizarre freak fest of blues psychedelia, doo-wop riffs, and musique concrète. The American education system and the cops and the losers with their convertibles paid for by mom and dad and the news media in Watts and the girls who dumped Frank Zappa were all targets of satire; nothing was sacred except for the myth of a figure named Suzy Creamcheese.

This was music for the cast-offs of the Great Society and for the poor bozos stuck waiting by the phone so long they had time to reupholster their cars. The album cost a fortune to make and didn’t sell, but at least the Beatles liked it, and Tom Wilson, the producer, got to drop acid to record the big freak be-in. By 1967, Ronald Reagan was in the governor’s office, and the LAPD was rounding up all the freaks, but, boy, was it exciting while it lasted! — Kyle Kramer

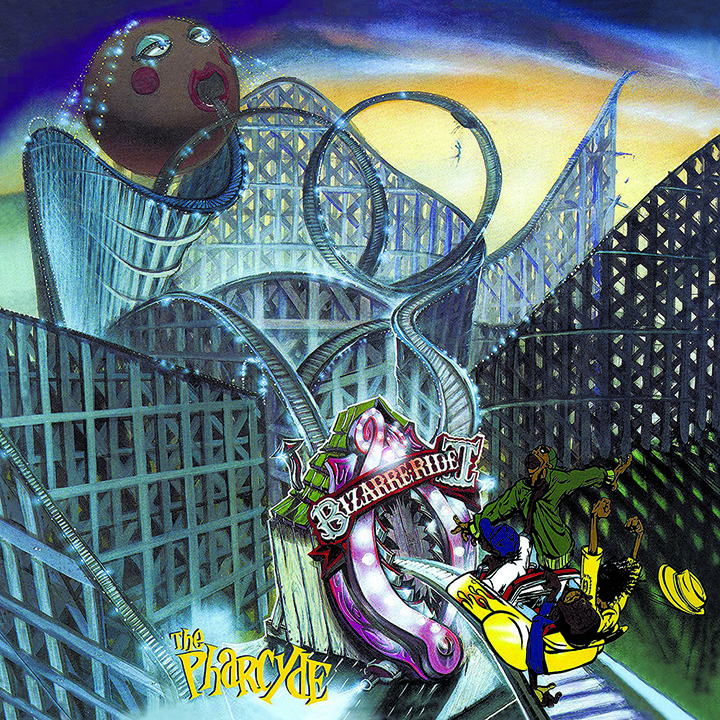

26. The Pharcyde — Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde [Delicious Vinyl, 1992]

A tragicomic masterpiece, Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde treats flaws as battle scars and personal rejections as a chance to try again. Fatlip, Slimkid3, Imani, Bootie Brown, and J-Swift announce their presence not with a roar, but with the hope that they’re not wack; hedging a bet never sounded this revelatory. A demented funhouse trip of Jim Morrison seances, Richard Pryor marathons, and relentless Good Life cyphers at class, Bizarre Ride is what happens when you break a mirror and the reflection laughs.

Stitched together by songs of heartbreak, joy, and chaos, the sound is fed through the lens of funk breaks, sing-alongs, and bug-out comedy. Rightful descendants of Parliament-Funkadelic, West Coast kinsmen to De La Soul, the Pharcyde are masters of the wildest style. J-Swift flips a James Brown sample and the group sound almost as funky as the godfather himself; their “yo’ mama” disses are the greatest rap song ever made from “The Dozens;” “Otha Fish” ranks among the genre’s finest breakup songs; “Passin’ Me By” is an existential simp anthem without peer.

The ease with which the South Central quintet bounce between grief, joy, and embarrassment is what makes Bizarre Ride more philosophical than merely just a fun party. They understand that the sting hurts less if you turn it into a joke. These are vignettes from the same novel, but somehow each one is an epic in its own right. See “Soul Flower (Remix),” where our boy Bootie sums up the entire shebang with 12 fucking words: “People promise you a bowl of cherries but don’t forget there are pits.” — Will Schube

25. Beck — Mellow Gold [DGC, 1994]

“In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” — Genesis 1:1

“In the time of chimpanzees I was a monkey.” — Beck Hansen, “Loser”

If you were anywhere in the vicinity of adolescence in the early ’90s, alternative rock was where you went to be sad or angry at the authorities and institutions you loathed and rejected. Beck changed the course of alternative music (and American culture in general) in the mid-’90s by adopting irreverence and humor as the preferred modes of anti-establishment behavior.

The “irreverence” on Mellow Gold isn’t jaded or cynical — it’s a means of miniaturizing unfathomably enormous concepts and skills and making them earthbound. At the time, Beck couldn’t rap or play guitar very well; he didn’t possess Bob Dylan’s symbolistic flair; he didn’t have very much money. But he did have attitude, loads of it, and enough creativity to recognize how his limitations accumulated into music rich in personality. The various elements of Mellow Gold — junk-shop sampling, teetering folk, vague hip-hop, and sloppy noise — formed a whole world emanating from a used boombox.

Beck was a major figure in a mid-decade movement in favor of cultural pluralism, where genres collapsed and tumbled into each other, random wordplay could assemble into accidental poetry, and high and low could tango and mosh. Most crucially, Mellow Gold encouraged people to seriously commit to their art without taking themselves so seriously, exemplified in the immortal lyric, “The sales climb high through the garbage-pail sky / Like a giant dildo crushing the sun.” — Tal Rosenberg

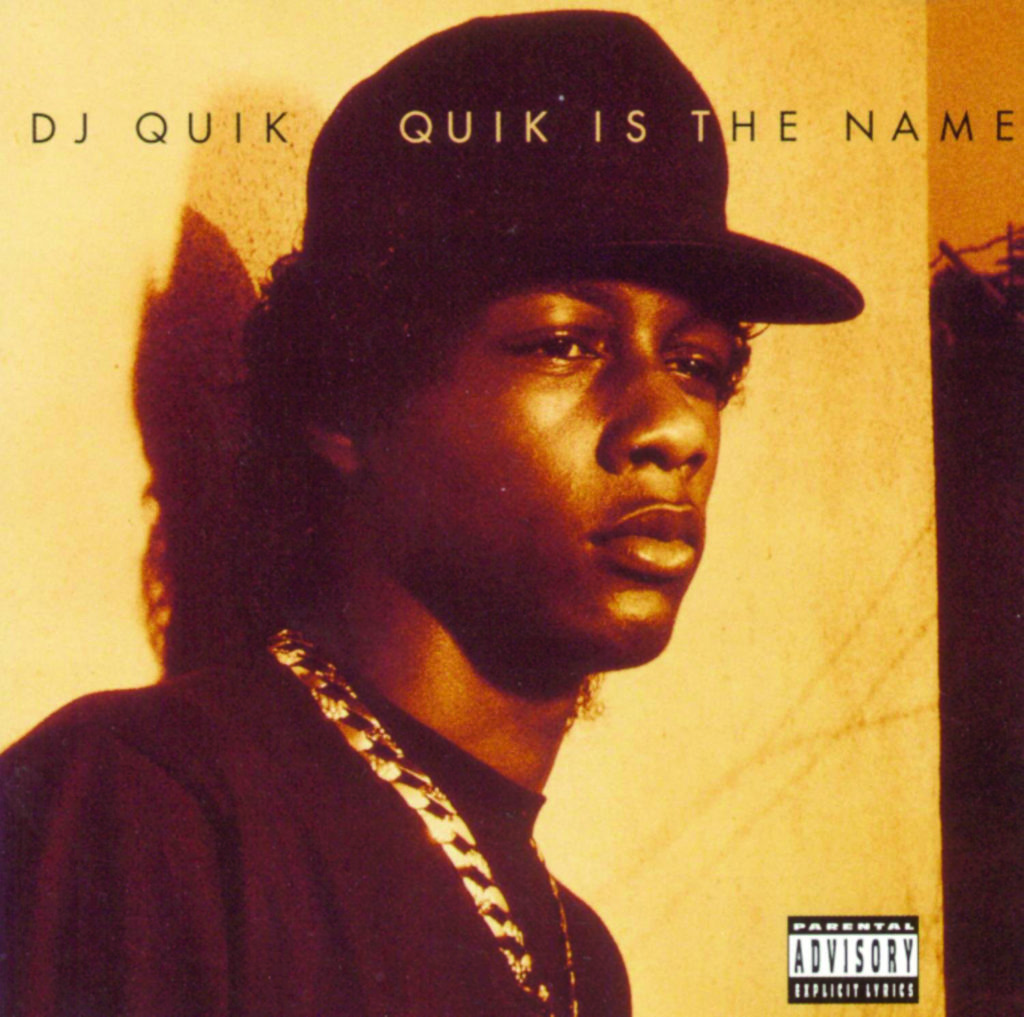

24. DJ Quik — Quik is the Name [Profile, 1991]

A 19-year-old from Compton spent 17 days in West Hollywood’s Westlake Recording Studios so that he could recoup the remainder of his month-long production budget. Three decades later, we revisit that two-week span of 1991 Los Angeles over and over for eternity; no matter what year it is, it’s always “Tonite.”

Quik Is The Name is an explosive debut, an energetic snapshot of youthful ingenuity. David Blake had been hustling at all costs to make it in music, mixing and scratching at local parties, selling homemade mixtapes, working various side jobs, and dealing. After hometown peers N.W.A. blew up, growing industry interest in Compton landed Quik a six-figure contract with Profile Records, and session time in the studio where Michael Jackson recorded Thriller.

A student of classic funk and soul, Quik flipped records and blended samples into a foundational G-funk sound that L.A. artists would build upon for generations. No asset of his complete skill set — MCing, DJing, or producing — lags behind the other. Quik’s cool, matter-of-fact delivery frustrates East Coast technical purists but makes him more familiar, as if you’ve always known this frozen-in-time, late-teens Piru from the 400 block of West Spruce Street whose lyrical depictions of everyday life are as smooth as his long hair.

He walks around with a bullet proof vest because he has a CPT sign written across his chest. Freezes 40s for Friday night parties and grips the toilet on Saturday mornings, pleading, “To the man up above to whom thanks I give, I’ll never drink again if you just let me live.” Smokes enough bombudd to include an entire reggae track. Chills with a 40 and a .38. on Aranbe and Spruce. Breathes vivid life into a few specific streets, from a bygone era. Leaves an enduring legacy for the city. — Will Hagle

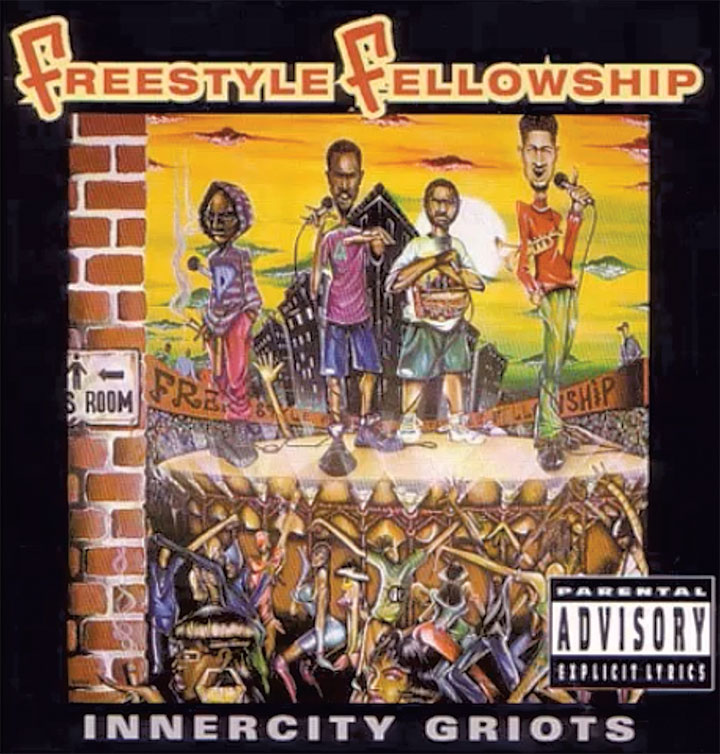

23. Freestyle Fellowship — Innercity Griots [4th and B’Way, 1993]

Freestyle Fellowship was Leimert Park’s answer to the question of how the hip-hop generation would preserve Central Avenue’s history. Aceyalone, Myka 9, P.E.A.C.E., and Self Jupiter sampled jazz as much as they vocally translated its improvisational and shifting time signatures, breaking from the rigid cadences of many contemporaries. Like Bird or Coltrane, each member could rhyme alone or in unison, running through words and contorting syllables, throwing exclamation marks on several frenetic phrases before seamlessly transitioning into more melodic passages.

The group’s sophomore album and major-label debut, Innercity Griots was the refinement of all of the unbridled styles they’d developed at The Good Life, the early ’90s Leimert open-mic turned breeding ground for LA rappers that offered a perspective antithetical to the invincible myths of G-Funk. As such, Innercity Griots was far more than guns, weed, and women. There were odes to the latter two, but there were also Gil Scott-Heron-esque ballads dedicated to the homeless. Fellowship turned the idea of cruising in a ’63 Impala into horror, the sight of one cruising with its headlights off the equivalent of seeing the grim reaper. Gangs and governmental neglect plagued the group’s section of L.A., but they promoted knowledge of self and Black unity over block warfare. They were the perfect foils to Dr. Dre and company, taking A Tribe Called Quest’s jazz leanings to their logical extreme while offering styles that generations of rappers have borrowed or failed to imitate. — Max Bell

22. Guns N’ Roses — Appetite for Destruction [Geffen, 1987]

In 1916, director Cecil B. DeMille purchased a verdant Los Feliz hilltop estate, where he wrote now-classic scripts and entertained silver screen royalty. 70-years later, four young men stinking of Marlboro Reds and sweating whiskey rented the DeMille house, then promptly annihilated it. They threw week-long ragers; they railed hard drugs. They ripped porcelain toilets out of the floors and hurled them into the yard. When nature called, they shit in the sinks.

Indeed, by the time Guns N’ Roses coalesced, the golden age of Hollywood had given way to a less glittery L.A. In more low-income neighborhoods, police brutalized residents as crack exacerbated violent crime, setting the stage for the riots. In the music community, the heady optimism of the ’60s Laurel Canyon scene had given way to coke-fueled, ’70s rock god decadence — which by the mid-’80s had devolved into white men in spandex snorting percocet at the Whisky. Sunset Boulevard it was not.

But while hair metal was a caricature of debased masculinity, G N’ R sidestepped the absurdity of their Sunset Strip peers on their 1987 debut by actually embodying a swaggering danger reflective of the city’s sharpest edges and darkest alleyways. The 12-track masterpiece featured heroin tales (“Mr. Brownstone”), the green grass of small towns (“Paradise City”), unbridled groupie indulgence (“It’s So Easy”), and L.A. as the jungle itself.

But while Appetite was forged in squalor and questionable life choices — those orgasmic moans on “Rocket Queen” are infamously real, with Axl Rose fornicating with Steven Adler’s ex-girlfriend right there in the recording booth — the final product is a tight, obsessively perfected and still face-melting portrait of Los Angeles at its glorious worst. — Katie Bain

21. Fleetwood Mac — Tusk [Warner Bros., 1979]

Ask any white person alive in the ’70s what the album of the “Me” decade was and they’ll likely say Rumours. But Fleetwood Mac’s blockbuster LP about breakups pierced the zeitgeist because its sparkling melancholy was reciprocal; both parties deserve at least some blame when a relationship deteriorates. The band’s tour de force of wanton selfishness is actually Tusk, with its eggshell backdrop approximating the perfectionist impulses of the band and the coke-covered surfaces of their furniture. If Rumours is a study of people wallowing in heartache, Tusk explores what self-pity curdles into afterwards — the boundless egos of bloodlessly libidinous, intoxicated, inconsiderate artists.

After the success of Rumours, Fleetwood Mac were given a blank check and the kind of creative freedom that David Lynch craves. They indulged — a double LP with superfluous packaging, 20 tracks, and stylistic shifts that would even make prog-rock bands raise an eyebrow. Tusk’s creative direction is undoubtedly guided by Lindsey Buckingham, but each song is the undiluted personality of its writer, whether it’s Christine McVie at her most polished and sun-soaked, Buckingham at his most finicky and angsty, and Stevie Nicks at her most Stevie Nicks. The result is a patchwork of soft rock, California folk, and nervy art-pop whose sequencing could only emerge from the internal logic of a pretentious rock star. Rumours is a reflective sojourn to Sausalito. Tusk is the definitive document of a late-’70s Angeleno asshole. — Tal Rosenberg

20. Steely Dan — Aja [ABC, 1977]

The ultimate test record for high-end stereo salesmen in the audiophile heyday of 1977, Aja was the summa of a band whose East Coast recluse cool could only be fully realized in the sun-stuck anomie of L.A. Recorded largely at night in the Masonic Temple on Butler Avenue, which then became the headquarters of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s Transcendental Meditation movement, and was then purchased by the ghostly heir to the Hormel meat-packing fortune who turned it into the legendary recording studio The Village, Aja was the product of the meticulous craftsmanship that allowed Donald Fagan, Walter Becker, producer Gary Katz, and lead engineer Roger Nichols to bridge an ocean of contradictions while rarely venturing outside the studio. It’s an album you have to listen to sober, to get all the trajectories down, and then play again when you’re high, to bring the amazement out.

The genius of Steely Dan began with the fact that they got to rock and blues through ’50s jazz, which gave their music a frame that encompassed the entirety of 20th century American music and songwriting craft. On Aja, the band paired Aretha Franklin’s rhythm section of bassist Chuck Rainey and drummer Bernard “Pretty” Purdy with tenor saxophone great Wayne Shorter on the title track. The credits on the rest of the album read like a who’s who of great studio drummers of the 1970s, including Steve Gadd (Paul Simon), Rick Marotta (Carly Simon and Warren Zevon), and Jim Keltner (Bob Dylan and nearly everyone else). Yet the precision of the sound no matter who was pounding the skins is proof of just how clear the band’s direction was. If the songs fronted their alienated lyrics, with nods to Nabokov and ’60s sci-fi, they were unambiguously in love with their musical roots.

The band’s trademark combination of coldness and warmth produced a uniquely East Coast version of West Coast cool that appealed to everyone in-between. “Peg” was a huge hit. “Deacon Blues” featured a hard West Coast bop solo by the hugely underrated saxophonist Pete Christleib, and the timeless stutter in the lyric, “They got a name for the winners in the world/I . . . I want a name when I lose.” My own favorite track is surely “Black Cow,” with the big-stepping monster bass line by Chuck Rainey that helped fulfill Donald Fagen’s ambition of finally getting one of his songs on the jukebox at Fatburger. — David Samuels

19. Suga Free — Street Gospel [Polygram, 1997]

What strikes you first is the specificity: the waves deep as Redondo Beach; perm silkier than Charlotte’s Web; panties clinging as they come off like the wrapping paper on Jolly Ranchers; a kitchen pantry so bare it only has “one potato with roots growing out of it.” This is Suga Free’s Pomona, where he’s a pimp with cartoon agency over the physical world one day and a dejected day-jobseeker the next. Street Gospel’s production is handled entirely by an in-his-prime DJ Quik — the greatest ever on the MPC-60 “and the 3000,” his partner is quick to point out.

But where Quik’s beats usually coax rappers deep into their pockets, here they merely suggest it. Suga Free’s inimitably elastic flows instead jackknife into each crevice before bounding to the next, leaving in their wake a string of details unverifiable by traditional means, but too strange to be imagined. In fact, the album is so regionally specific that while it barely translated north of Fresno or east of Vegas, its DNA traces to current L.A. rappers as gleefully formless as Blueface and as classically rigorous as Kendrick Lamar.

Street Gospel has plenty of schoolyard jokes and stone-faced threats stemming from its author’s profession (and some asides that underscore its horror, like when he brags about raking in “a thousand dollars a day multiplied by each blister” on a prostitute’s feet). But while he was mastering the outlandish, Suga Free smartly dotted the album with bits of the mundane. See especially “Secrets,” where he casts fights with his father and mother not as righteous struggles but as childish petulance he’s happy to leave in the past. He’d been humbled, after all. At the end of that song’s second verse, he recounts trying to strike out on his own in L.A. County’s legit economy: “Trying to get a job with a cross tattooed under my left eye / They never called me back in interviews / It was ‘Hi,’ and ‘Bye.’ — Paul Thompson

18. X — Los Angeles [Slash, 1980]

Punk is urgent, but Los Angeles reaches beyond urgency. It’s a disaster flare, a last resort, a bloodletting. Its muscular instrumentation hits so hard you almost miss the lyrics. But behind the demented wall of sound is a postmodern noir den, a literary collage of petty theft and heartbreak, robbery, and rape. The ugliness of poverty, the violence of bigotry — X pulls up the floorboards of 1980 L.A. and finds termites.

Nothing appears in a vacuum. Los Angeles was produced and partially funded by Ray Manzarek, co-founder and keyboardist of the Doors. His involvement legitimized X as the fulcrum between L.A.’s classic-rock past and its punk future. He didn’t just get it, he sold it. Besides producing the album (and their next three), Manzarek played organ on four tracks and gleefully turned a cover of “Soul Kitchen” into a trucker speed freakout that makes the Doors sound downright timid.

With its opening riff lurching down-DOWN-down like a broken elevator to Hell, the title track is the opposite of a love letter. “She had to leave Los Angeles,” it starts. By the chorus, as Exene sings “get out, get out, get OUT” at fever pitch, you wonder if she’s trapped elsewhere.

“No one is united and all things are untied.” Compared to New York City or London, L.A. punk malaise was stubbornly apolitical. Los Angeles is personal, but it’s not literal. The songs are idiosyncratic short stories, character sketches of desperate losers who maybe believe in nothing.

John Doe and Exene Cervenka — Johnny and June of the damned — weave hoarse, trembling harmonies from these deeply alienated lyrics. Whenever their vocals threaten to get too goth-poet ethereal, Billy Zoom’s slammin’ guitar and DJ Bonebrake’s unerring rhythms nail them to the stage. Forty-some-odd years later, it still works, even as they approach new records for longevity as a rock band with a fully intact founding lineup. It’s frustrating and fitting that X isn’t given pride of place in mainstream punk history. Like the best of their city, they’re a poorly-kept secret: massive and inescapable and somehow underrated. — Kaleb Horton

17. Ice Cube — AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted [Lench Mob/Priority, 1990]

The year is 1990, and O’Shea Jackson is meeting truly thorny career questions with certifiably unfadable answers.

What will he do after splintering from the most successful and galvanizing rap group since Run DMC? Hit up Public Enemy and the Bomb Squad.

How will he top his intro-turned-apotheosis, “fuck the police coming straight from the underground?” Double down and declare himself AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted.

And where will Ice Cube go with his city’s police department, sheriff’s office, and media apparatus trailing his Black Chucks step-for-step? To New York City for a vengeful malt liquor bender, of course.

Cube’s solo debut on Priority Records, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted is nothing short of wholly disarming. While bloodless conmen parlayed Reagan into Bush and white Nicaraguan powder into Black American death, South Central became the theater for cultural revolution. And two years after Daryl Gates’ LAPD drove a battering ram through apartments on 39th and Dalton, two years before that same paramilitary capital death club brutalized Rodney King, this is the album that best distilled the rage and paranoia in this city.

Proudly anti-pop and largely anti-capitalist, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted isn’t Cube’s most musically ambitious album (Death Certificate) or his most well-known (Lethal Injection). But it remains his statement work, an abrasive and gnarly missive to absolutely everyone except his Lench Mob associates and all those stolen souls stuffed into 6-by-8 cells. And every subsequent hood-stamped rap prodigy south of the 10 (Snoop, Kendrick, Freddie Gibbs, Drakeo the Ruler, all those still to reveal themselves) will forever be spiritually indebted. — Steven Louis

16. Black Flag — Damaged [SST, 1981]

Henry Rollins didn’t have lyrics in hand when he went into the booth to record “Damaged I,” the final track off Black Flag’s debut Damaged. The song became more spoken word than a composition; ultimately, the producer Spot decided to go with Rollins’ first cut, but not without hearing multiple takes of a thorned, improvised monologue.

The rest of Damaged was written with a buzzsaw, sliced with uneven jazz chords, then dragged through sand and mud. The 35-minute debut rips through drinking songs until it slips into nihilism halfway through. “There’s no relief for a person like me,” Rollins bays on “Depression.” “I need help before it’s too late,” he caterwauls on “Room 13.” It would have felt solipsistic if it weren’t for the frontman coming to Los Angeles with D.C. influences like Bad Brains and Minor Threat, who wrote poetically and politically. Greg Ginn — the band’s jazz enthusiast — happily worked with the subject matter, delivering squealing solos and tempo shifts.

This was new to L.A. Punk was starting to feel textbook before Damaged. Hollywood had its favorites, but there was a particular lacuna in the transition from a comparatively glossy band like X and a tragic one like Germs. In a brief moment when hardcore didn’t know what it could do, Black Flag proposed something different for the West Coast.

Damaged grabbed beach boys and told them to scream until the throat bleeds, throw atonal chords into breakdowns, and recite poetry. Hardcore went on to mushroom up and down the coast; it gave us peak Circle Jerks, Minutemen, T.S.O.L., and even Dead Kennedys. Black Flag’s debut is an undeniable relic of the South Bay, where the waters are now toxic and there are a dozen new things to be depressed about. Once again, we suffer from the boredom of despair, and it necessitates a timeless album of unrehearsed screams. — Lisa Kwon

15. Flying Lotus — Los Angeles [Warp, 2008]

As the first decade of the 21st century came to an end, local physical spaces found themselves connected to a global network of MySpace pages that vaporized distances and shriveled stylistic expectations. By the end, we were all ushered into the new status quo of voracious social networks, streaming, and bedroom pop music. But for those brief few years, it was all bent out of distinct shape into rhythmic contortions and sub-vibrations. The era’s global beat scene was most intensely audible in Los Angeles, where local heads who had been biding their time for close to a decade found themselves thrust onstage. The joy and spirit of these early years thrived in two places: at Low End Theory, the scene’s weekly club night that went on to become a global phenomenon, and on Flying Lotus’s second album.

A series of hazy instrumental sketches that go bump in the night, Los Angeles is full of skittering drums, crackling samples, and warm bass. It’s an ode to the potentials hidden within cracked software, late night drives, and clouds of smoke.

Most importantly, the album — and the club night it remains inseparable from — represented the long-overdue addition of Los Angeles to the map of turn-of-the-century electronic music hubs and the anointing of a young Black genius as the figurehead of a movement that would go on to ripple across pop culture. — Laurent Fintoni

14. Sublime — 40Oz. to Freedom [Skunk, 1992]

40oz. To Freedom is a love letter to Long Beach. A tattooed wildcard full of profane stories about the streets, Bradley Nowell loved weed, his Dalmatian, and house parties. He sang for those who could barely pay rent. Sublime’s first masterpiece encapsulates the drunk-at-noon, inked antiheroes of the 5-6-2 who, above all else, hate the man and are searching for freedom however they can get it, however fleeting it may be.

Titled after their ode to “feeling good even though I feel bad,” the album offers us permission to be sloppy and raucous. It’s not even Bradley’s wail that gives us this privilege. It’s the transmutation of “Rhapsody in Blue” into ska in “What Happened.” It’s the sample from Reefer Madness followed by the sound of a bubbling bong in “Smoke Two Joints.” It’s all the Grateful Dead, Minutemen, and N.W.A. references. From top to bottom, 40oz. To Freedom is a testimony to breaking the rules, even when it’s a little distasteful. Hell, Sublime spawned an entire genre of shitty, white-led reggae bands who tried to emulate them… and mostly failed. Why? Because no one is Bradley, and Sublime’s style started and ended with them. That’s how real they were. Their fusion of ska/punk/reggae/rap is emblematic of Long Beach’s cultural diversity. It captures a flavor only a group of music-obsessed locals who spent their youth together could have channeled. 40oz. started out as the sound of Long Beach, but it evolved into the iconic coastal soundtrack of Southern California. — Mary Carreon

13. Neil Young with Crazy Horse — Everybody Knows This is Nowhere [Reprise, 1969]

Musically speaking, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere is the record of Neil Young inventing Neil Young, accompanied by Crazy Horse. It’s like listening to Niels Bohr sketch the atom late at night in the Hollywood Hills after a long day at the beach in Malibu. Legend has it that Young wrote the album’s four best songs — the title track, “Cowgirl in the Sand,” “Cinnamon Girl,” and “Down by the River” — in a single afternoon under the influence of a 103-degree fever, an origin story that captures the combination of dark intensity and aching vulnerability that would make Neil Young the greatest songwriter and performer to emerge from the L.A. canyons back when they were paved with gold.

Nowhere was technically Neil Young’s second solo album, after the wildly mis-labeled Neil Young, a well-polished and entirely forgettable collection of songs that any talented aspiring male songwriter might have recorded in Hollywood anytime between 1967 and 1971. On Nowhere, Neil said goodbye to all that, before joining up with Crosby, Stills, and Nash, who were all hugely talented musicians in their day, and who all wound up as footnotes to Neil Young’s genius.

Unjust? Unfair? Cruel? The world is often that way, yes, but not always without reason. Neil Young risked more than his contemporaries did. He stripped himself bare, revealing both his childhood fear and his inner rage, as well as his childlike belief in the power of love as an antidote to loneliness. He fronted the high, wounded falsetto that a lesser artist would have seen as an impediment to stardom. He was a perfectionist whose backing band sounded like it came from someone’s garage. Neil Young’s music was about a young man setting out in pursuit of the real, and Everyone Knows This is Nowhere was the moment where he decided to be Neil Young without blinking. It retains that sense of high-risk immediacy over five decades after it was recorded.

In an age where the personal has been subsumed by the digital tsunami that masquerades as politics but whose true object is the desecration of souls, Everybody Knows This is Nowhere is a reminder of what the opposite sounds like: art. Remarkably, everything that would follow is right there on the first Neil Young record. — David Samuels

12. 2Pac — All Eyez on Me [Death Row/Interscope, 1996]

Hennessey, enemies, and penitentiaries walk into a bar. It may sound like the worst night imaginable, but 2Pac created a classic filled with certified hits fueled by these three items. Upon his release from a New York prison, ‘Pac arrived at Tarzana’s Can-Am studios ready to do nothing but smoke, drink, and rap, and he walked into the greatest murderer’s row of talent ever assembled. Where else but Death Row? Where Suge Knight presided over his reign of terror, DJ Quik engineered the sessions, and Dre had left a couple of beats behind before fleeing. The environment there was one of a kind: full of Crips, Bloods, multi-platinum artists, producers, chronic smoke, models, drugs, every type of inspiration and distraction possible.

While 27-song albums are normal in the streaming era, they were once wildly ambitious. The first CD finds ‘Pac rapping in the mirror, reflecting on his prison sentence, explaining his fast-paced lifestyle since his release, speaking on friends he’s lost along the way, and the unfair treatment of Black people in the system. The best song is literally a seven-way tie. You can have your choice between “Ambitionz Az a Ridah,” “All About You,” “2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted,” “How Do U Want It,” “California Love,” “Only God Can Judge Me,” and “I Ain’t Mad Atcha.” On disc two, he raps in front of a two-way mirror, unconcerned about who’s listening but aware that all eyes remain on him. Over half of those tracks will be played on KDAY until they retire the format (and even then).

Themes, instrumentals, and concepts from this album have since been used by everyone from J. Cole to Boosie, Fabolous to YG, No Limit to Cash Money, and so on down. On the West Coast, whenever rappers want to restore the feeling of the ’90s, they don’t throw on a Penguins jersey, a white chronic leaf snapback, and an all red suit; they opt for a bandana (tied in the front), a leather vest, a gold Rolex and a Cuban link Death Row chain. It’s basically The Game’s whole career. Kendrick Lamar, who proudly admits his 2Pac influence, ended his whole To Pimp a Butterfly album with a 2Pac interview (it was originally titled Tu Pimp a Caterpillar, get it… TUPAC).

All Eyez on Me is generationally impactful, one of the few hip-hop albums to be certified diamond, and one that’s eerily prophetic, as though ‘Pac was all too aware of his fate. He understood that his life might be on the verge of ending but created a work that insured that he would forever remain the West Coast’s favorite outlaw immortal. — Victor Ulloa

11. The Beach Boys — Pet Sounds [Capitol, 1966]

When it comes to sunshine-and-surfboard clichés, Pet Sounds is the least L.A. of all the Beach Boys’ albums. But it’s still a California product through and through. It’s just that when Brian Wilson set out to create this magnum opus at various Hollywood studios in 1965 and 1966, the spirit he was going for was less Mamas-and-Papas pop and more akin to the visionary pursuits of David Axelrod, another producer from L.A. who around the same time figured out ways to use the studio as his instrument.

Pet Sounds is full of beachy good feelings, yes, but the quirky, quasi-orchestral arrangements and hauntingly crystalline vocal harmonies just as often speak to sadness, even a sense of doom: Listen to Wilson’s achingly measured melody on “Don’t Talk (Put Your Head on My Shoulder),” his voice making ghostly bends in a way that almost seems inhuman. Clearly for Wilson, the door was closing on more innocent times. Pet Sounds reckons beautifully with the power of joy and the pains of growth alike through the kaleidoscopic complexity of Wilson’s arrangements and production and Tony Asher’s lyrics. Of course, countless artists have since gone on to tap into this same musical and emotional territory — including the Beach Boys’ British contemporaries the Beatles, David Bowie, Talking Heads, Weezer, Animal Collective, and a whole generation of post-Great Recession California garage bands like Wavves, Best Coast, and Allah-Las. But many of these younger bucks haven’t come close to the master document. Pet Sounds remains one of pop music’s most powerful odes to the purest human feelings, revealing different shades with each listen. — Peter Holslin

Bow Down (The Top 10)

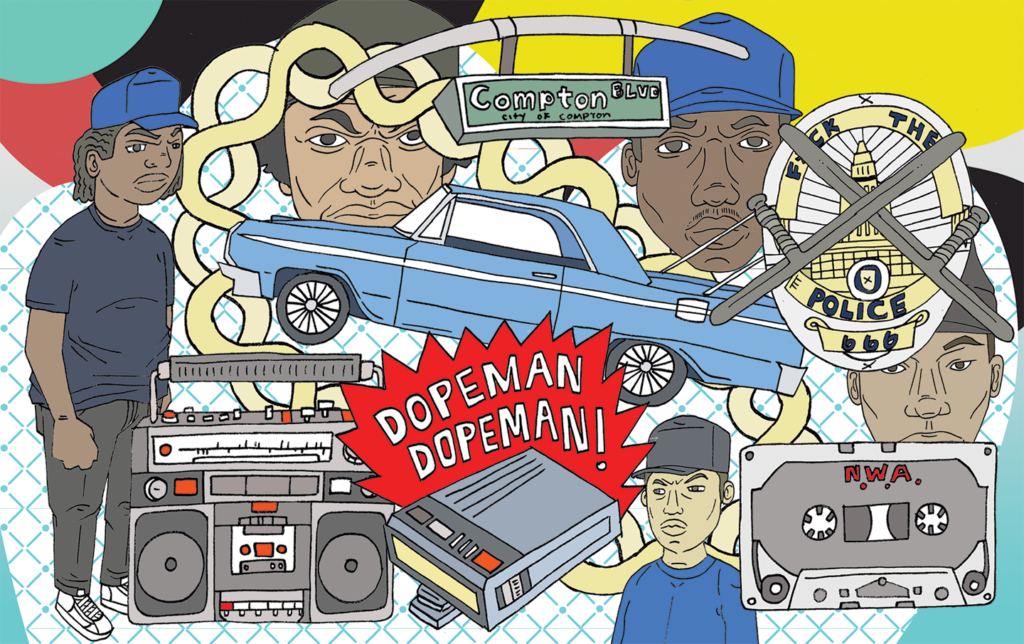

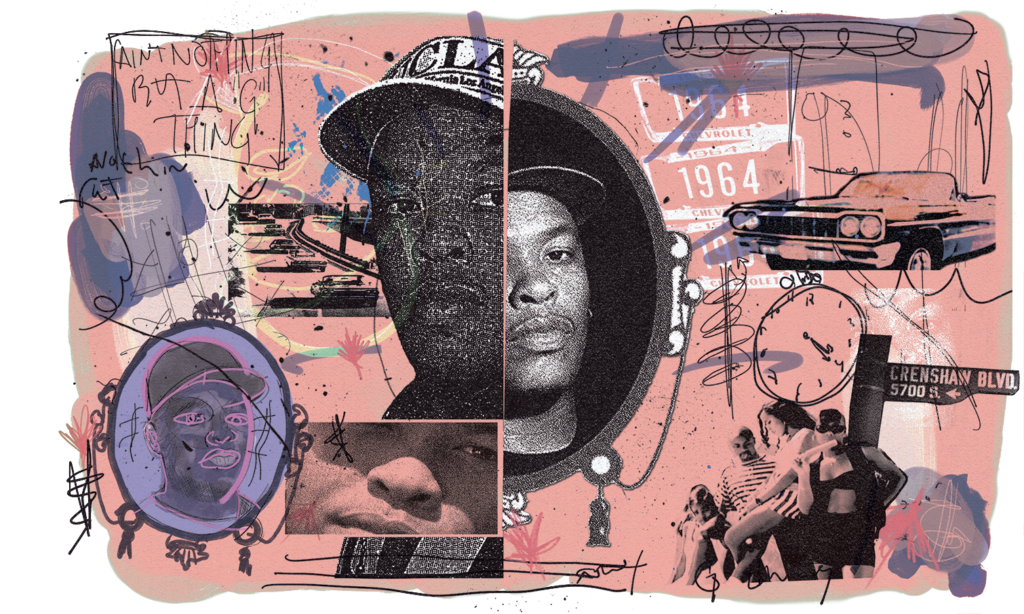

10. N.W.A. — Straight Outta Compton [Ruthless, 1988]

Imagine a time in history when N.W.A. and their legacy doesn’t exist. A time when Compton, a suburb within Los Angeles County, wasn’t a household name (or a hotbed for hip-hop talent). A time when “Fuck The Police” wasn’t a commonly used phrase. This was life prior to August 9th, 1988; from that day forward, the world was forever changed. What if Eazy-E never pays Alonzo Williams $750 to get a meeting with Jerry Heller (the man who got N.W.A. their deal at Priority Records)? Do we get other Compton rap greats like DJ Quik and Kendrick Lamar? What about the other branches of the N.W.A. family tree such as Eminem, Snoop Dogg, 50 Cent, and Bone Thugs-N-Harmony? N.W.A.’s tentacles are STILL all over popular culture some 30 years later; this album was the genesis.

N.W.A.’s debut album*, Straight Outta Compton, plowed through American music like a batteram. Sure, we’d gotten a glimpse of L.A. life thanks to Ice-T, but N.W.A.’s debut kicked the door off the hinges for West Coast hip-hop. We witnessed the strength of street knowledge in real time, where Raiders and Kings hats became must-haves uniforms in all corners of the United States. Eazy-E, Ice Cube, Dr. Dre, MC Ren, DJ Yella, and, on this album, Arabian Prince became cult heroes and certified street reporters.

The lyrics could be jarring, inappropriate and shocking (see: receiving fellatio from drug addicts on “Dopeman”) — but also heavy on social commentary and socio-political issues (see: the entirety of “Fuck tha Police”). Yes, the explicit lyrics sticker and surrounding controversy helped move units, but it was the beats, rhymes, and instructions to “Express Yourself” that helped this album sell over three million copies.

Dr. Dre’s production, Eazy-E’s evil chirp voice, and Ice Cube’s literary aggression gave us a bird’s eye view into the good and bad of the California dream. Nothing in rap sounded like Straight Outta Compton, and it soon birthed a generation of imitators. It’s still one of the few rap albums that could seamlessly shift from funny to dead serious, one that invaded major cities and suburbs alike, and went from kids hiding the cassette from their parents to an actual big screen blockbuster in 2015. Parental Discretion Iz (still) Advised. — Andrew Barber

*We do not count 1987’s N.W.A. & The Posse as their debut

9. Madvillain — Madvillainy [Stones Throw, 2004]

It’s hard to imagine something more mercenary: an out-of-towner with a weathered mask in his carry-on, the secret meeting in a concrete bomb shelter in Mount Washington, a contract scrawled on a paper plate. This was the genesis of Madvillain, the collaboration between Oxnard’s Madlib and MF DOOM, the London-born, Long Island-bred rapper with no face. The LP very nearly saw its commercial release scrapped after a working version was lifted from Madlib’s São Paulo hotel room and leaked online; when the pair reconvened, DOOM re-recorded all his vocals in a lower register, and Madlib augmented the beats with some samba loops, as if out of spite.

In the same way that Madlib’s samples bristle against one another — their textures mismatched, their original contexts collapsed — he and DOOM seem to be at mesmerizing cross purposes. Where the beats are composed of a thousand component parts that have been refitted and arranged just so, the raps flaunt a sort of first-thought impulsivity. They resist conventional structure or narrative arc; many take their names from whatever noun DOOM throws into the first or last line of the verse (“Curls,” “Money Folder,” “Great Day,” and so on). When he does decide to address a topic head-on, he is ruthlessly efficient: The second verse of “Strange Ways” undermines the entire moral framework used to justify American wars in the Middle East in just 12 bars. One is left to imagine that no one at the label cut a check for the last four.

Madvillainy won immediate acclaim from critics, but more telling is the way its influence tentacled through L.A. and around the world via the internet. The psychedelic bent to its beats helped shape the Low End Theory scene that was so central to the city through the ’00s and ’10s; DOOM’s raps spawned one splinter cell after another. Artists as globally popular as Odd Future down through the niches of SoundCloud and street rap owe the album a tremendous creative debt. Curiously, it’s a bit of a regional Rorschach test — some young MCs who strip the Madvillain style for parts scan immediately as East coasters, while the broader vibe of the project could not be more conspicuously Angeleno. Despite all of this, the duo never completed a proper follow-up. This might be disappointing but is thoroughly appropriate. If Madvillainy is about anything, it’s about the justifiable fear of the unseen. It’s about the shadowy figures who slip into the city, terrorize it in ways baser crooks could never imagine, then disappear for good. — Paul Thompson

8. Alice Coltrane — Eternity [Warner Bros., 1975]

There’s a meditative quality to living in Los Angeles that reveals itself to you over time. It’s not the obvious kind that the city sells itself with but rather a more subtle vibration that you can tap into and use to commune with the geographical and cultural expanse represented by the idea of L.A. Alice Coltrane made this vibration manifest on Eternity, the first album she released after moving to Los Angeles in the mid-’70s.

At this point of her career, Coltrane had become dexterous at weaving together stylistic filaments — gospel, R&B, jazz, but also Indian and Western classical music — into a spiritual tapestry of sonic ecstasy. In “Om Supreme,” the chants repeat a mantra of being called and met at a specific place. The first place invoked is “California” followed by various Lokas, a Sanskrit term for plane of existence. It’s as if Coltrane understood that beneath the seeming vulgarity of it all there was an energy in Southern California worthy of communing with. Eternity’s impact on the musical landscape of L.A. is still felt today: from the regularly recurring new age revivals that animate various scenes to the beats of Georgia Anne Muldrow and her grandnephew Flying Lotus, the impassioned lyrics of Jimetta Rose, and the harp-led compositions of Low Leaf. As with the city, Coltrane’s music was no longer a single, easily understood entity, but rather a nebulous whole in which getting lost meant finding yourself in new ways. — Laurent Fintoni

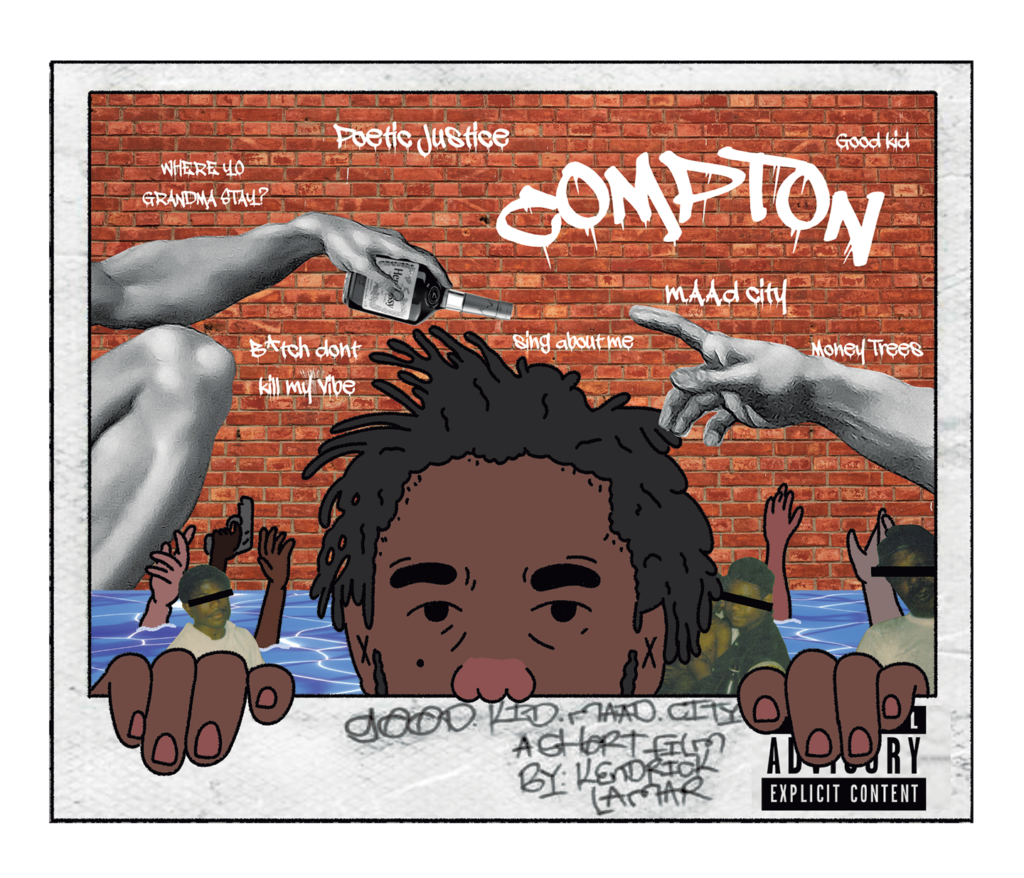

7. Kendrick Lamar — good kid, m.A.A.d city [TDE/Aftermath, 2012]

It starts innocently enough: a group of friends in a mom’s borrowed van, smoking and freestyling in South Central. This leads to a peer pressure-assisted robbery, a hookup with a girlfriend, and then the repercussions of the robbery. That’s more or less the “plot” of Kendrick Lamar’s major label debut, his best album, and what many consider to be the best album that this young century has produced.

Kendrick’s “dry run” — the mission statement album/mixtape Section.80 — featured songs that blended the intensely personal and the cosmic, but even the hardest riding advocate for K.Dot’s early work might’ve tempered expectations for the follow-up. What came next took the ancient, universal plot laid out above, and shattered that narrative into a million pieces, leaving it to the listener to piece together the story of a young man growing up, leaving behind K.Dot as he became Kendrick Lamar.

Good Kid’s power lives in the density of Kendrick’s verses, which take the set-up and punchline format of a clever mixtape 16 and merge it with narratives about the soul-crushing, systemic cycle of gang violence and the death of his friend Dave. It lives in his eye for casual and devastating observation — how an activity as common and mundane as parking your mom’s van, throwing on a beat tape, and freestyling is therapy for young men without the resources to want or know they need the real thing. It lives in GKMC’s cinematic structure, a Russian nesting doll of novels in novels that channel Singleton and Cube, but also Roth and Bellow.

This “model,” the rockist mission statement, the postmodern, first-person novel, the full album experience related as something closer to cinema than music, briefly took over rap in the early ’10s. Kendrick reintroduced storytelling and the mythmaking origin story on an LP scale. A very old and cutting-edge vision of branding. What separates Kendrick’s work is the secondary awareness, the layers, the heft, the way he refuses to settle for the stereotypical characters we think we know by now to live as rote caricatures on the page. In both skit and verse, the way characters like his dad come to life surprise you, and break your heart over a missing set of dominos. — Josh Kaplan

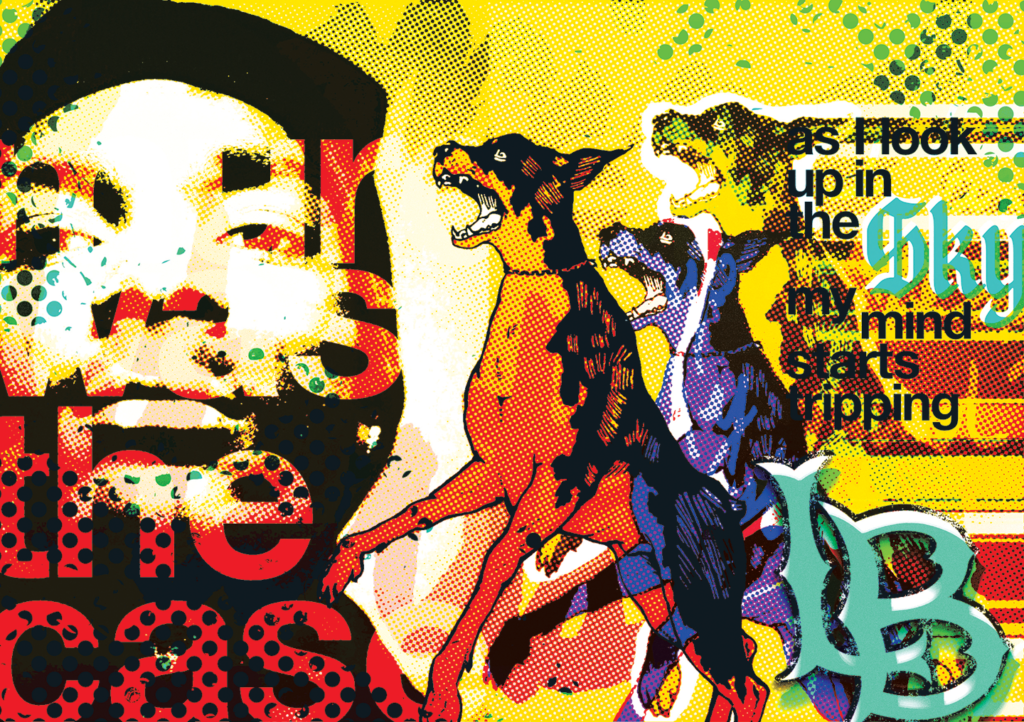

6. Snoop Doggy Dogg — Doggystyle [Death Row/Interscope, 1993]

The Chronic introduced G-Funk to the world, but Snoop Dogg’s immortal debut was the one that permanently embedded it in the cassette decks, CD players, and subwoofers of cars swerving from sea to sea. Over some of Dr. Dre’s most iconic compositions, a barely legal Snoop Dogg repurposed the soul of his parents’ funk records as bangers for steel-bodied Chevys and Cadillacs rigged with hydraulic switches. Sunny days in traffic on E Ocean Boulevard, clouds of weed smoke thicker than smog and fog floating along the Long Beach port, cutting through the heart of Long Beach. White conservatives and liberals alike engaged in a mass panic from the allusions to casual sex and his pending murder trial.

While Tipper Gore and company decried Snoop (represented by Johnnie Cochran), listeners flocked as Doggystyle sold an unprecedented 806,858 copies its first week: the best-selling debut album ever at the time of its release. It was purportedly misogynistic because of its depictions of consensual group sex and engaging in intercourse with someone you don’t exactly trust, but the first verse to be let off on the album was carried by the voice of a woman, Lady of Rage, who made sure her afro puffs were sufficiently fluffy. The hits defined a generation — not just L.A. O.Gs. in locs and with blue bandanas in their pockets, but kids across the country who dreamed of palm trees and cannabis leaf socks. Gangsta rap had garnered a reputation as music for both revolutionaries and knuckleheads, but with Doggystyle, Snoop turned it into the kind of party music that was unrivaled in rap for over a decade.

Hit after hit after hit (“Who am I [What’s My Name],” “Gin N Juice,” “Doggy Dogg World,” “Ain’t No Fun [If the Homies Can’t Have None]”), with that sub-atomic bass and whining synths. “Murder Was the Case,” blending sober fatalism with a prevalent lust for life, was such a powerful and foreboding statement that it prompted a 14-minute short film and an accompanying remix. Snoop’s flow over Dre’s beats to this day feels seamless. Reverence for both the Dramatics and Slick Rick, the latter (an interpolation of the immortal “Lodi Dodi,” which wasn’t an official radio single but still received substantial airplay) over a sinister Dre beat which increased sales for Cool Water Cologne nearly 1000 percent.

Walking on an ocean of Tanqueray on blue Chuck Taylors obscured just so by Dickies pant legs, cloaked in an oversized flannel, Calvin Broadus’s destiny was to hang a platinum plaque on the V.I.P. Records sign. He accomplished so much more, creating a monument for a city he single-handedly made a rap capital. — Martin Douglas

5. Minutemen — Double Nickels on the Dime [SST, 1984]

Punk has a reputation for being angry, repetitive, and one-note. Minutemen are the opposite of that, and they’re some of the truest punks of all time, and their third album Double Nickels on the Dime is an 80-minute, 45-song masterpiece. An epic that blows up every notion about what this music can be. Mostly, though, it’s fun. Jump in. Trust them. At first it sounds like they’re just riffing, but then it sounds like they’re inventing, writing the album in front of you, in a garage, and you’re sitting there in a folding chair. The music is strange, often goofy, packed with loop-de-loops of free association and collage-like lyrics.

You want to ask, where did these guys come from? Two childhood friends from San Pedro, D. Boon and Mike Watt, so close they could be brothers, so close they share a private language (many of the lyrics sound like inside jokes or nonsense), teach themselves guitar and bass. Then they grow up and learn punk rock in Hollywood. They’re fucking corndogs, they jam econo, and the rest is history.

There’s not another album like this, so funky, so diverse in its influences, so jazz-inflected, so full of contradictions. Some lyrics were written by Henry Rollins, some reference Ulysses, and some were pulled from a landlady’s note about a broken shower.

For an album so progressive I almost want to call it avant-garde, it’s completely unpretentious. Beneath the layered references, angular chords, and frantic rhythms, it’s a simple ode to the joy of jamming. It’s a salute to Los Angeles as the city of self-invention, where a couple of working-class Pedro boys can DIY their way into post-punk. They held day jobs through the band’s entire run, because careerism would have ruined it. Their first-ever music video, for “This Ain’t No Picnic,” depicts the band playing in rubble while Ronald Reagan machine-guns them from a fighter jet. It cost $600 and was nominated for an MTV video award. To jam econo is to play — not just music, but to play, period.

Commercially unsuccessful, beloved by a few heads, and reappraised higher and higher with time, Double Nickels still pops up like a recessive gene. The theme song of MTV’s Jackass is an instrumental version of “Corona.” Sublime sampled “History Lesson Part II.” It was either the start of something or the end of something, a license for punk and hardcore bands to start ignoring imaginary lines of genre.

D. Boon has been dead longer than I’ve been alive, and kids don’t play punk anymore. Nobody jams econo because they don’t even have vans. But the spirit of the Minutemen lives on. Every time some kid yells something hormonally motivated but honest into his laptop microphone and puts beats to it, every time somebody does a weird un-choreographed dance for their phone, that’s the Minutemen attitude.

Finally, this either has nothing to do with the album or everything, but it needs to be said because everybody who was there knows: Mike Watt is the most humble guy in the world. He’s got his van, he’s got his bass, he’s got his gear, and that’s all he needs. — Kaleb Horton

4. The Doors — L.A. Woman [Elektra, 1971]

Jim Morrison laid bare L.A. Woman’s animus to biographer Jerry Hopkins two years before the band cut the album’s first track. Morrison didn’t blather on about boozing or storming heaven with psychedelics. He mused about meaninglessness. He confessed a fondness for futility. Morrison was no nihilist. He tethered his take on “action” to “freedom.” Imagine the look on Hopkins’s face when Morrison, six or more drinks deep, revealed that he “starts outside and reaches the mental through the physical.” It’s the patois of the AA group therapy guru, a levitating David Carradine stunt-double freighted with turquoise jewelry and macrobiotic diet. Yet Morrison makes the abracadabra menacing. It’s a process. A procedure. And L.A. Woman is its demo: a crime tape, bad-dream catcher wrapped around West Hollywood.

Musically, we’re gifted more of the same — an off-putting melange of styles (blues, boogie, altar-call gospel, lounge). Yet here it’s staggered with lyrics that steer clear of Morrison’s jejune take on symbolist poesie and instead toggle between both transformation and preservation in ways that are both authentic and confrontational. The space between these modes is L.A. But Morrison refuses to locate it. Instead he frees it with meaninglessness. L.A. is uptown and downtown and all around. L.A. is rich and poor. L.A. is ready-to-hand but out of reach. L.A. changes your weather, your luck, your view. L.A. begs for one of you people to come on and set her free. L.A. is a thunder word that claps “motel money murder madness.” It’s the sound of a band waking itself. Stripped bare, reminiscing, peering bleary-eyed through a glass darkly at its own end. Pretty neat. Pretty good. — Stewart Voegtlin

3. Joni Mitchell — Blue [Reprise, 1971]

Blue is the travelogue where Joni Mitchell found herself: a pop-music auteur in perpetual motion with an open-tuned guitar, a dulcimer, and the electric images in her head. She created filmic songs about tourist towns and cave-dwelling freaks, about the intellectual charge of infatuation, about the pleasures of dancing so hard you shred your stockings — about how thinking and feeling require each other. Blue maps Mitchell’s adventures traveling in Greece, Paris, “maybe Amsterdam,” “maybe Rome,” but Los Angeles is its gravity center. California is her liberated heart, her compass, the Laurel Canyon folk-rock groove behind the wind pushing her to fly.

Every Blue song is a masterpiece within a masterpiece. Set to her stirringly unresolved “chords of inquiry,” the specificity of detail in her language created a new paradigm for what could potentially be said in a pop song, for how much unguarded real life a lyric could hold. The mystic “Little Green” was about the daughter she gave up for adoption (though no one knew it then); “All I Want” was a declaration of unequivocal agency. The critic Greg Tate once posited that Mitchell anticipated a hip-hop sensibility, and what other Canadian can you picture singing, sorrowful but assured, that “I shouldn’t have got on this flight tonight,” or “I’m so hard to handle, I’m selfish and I’m sad/Now I’ve gone and lost the best baby that I ever had”? The oxygen of pop half a century on, Blue is vulnerability as philosophy, in cerulean tones. — Jenn Pelly

2. Dr. Dre — The Chronic [Death Row/Interscope, 1992]

Dr. Dre has defined the sound of L.A. rap for generations. In the ’80s, he soundtracked roller rink jams as a D.J. in the World Class Wreckin’ Cru before trading his sequined garb for a Raiders cap and arranging N.W.A.’s militant, anti-cop anthems. Heading into the ’90s, on his first solo album, he emerged from weed clouds and the scorched-earth feud between him and Eazy-E. You could smell the toxic smoke, too, coming from the South Central blocks set ablaze during the 1992 L.A. uprising.

Allegedly recorded with looted goods littered around the studio, The Chronic was part pro-marijuana treatise, part searing diss record, and part street-level sociological reportage. It documented the governmentally imposed ills affecting Black and Brown Angelenos — the conditions that motivated banging, slanging, and looting and that necessitated, nerve-calming baseball-bat joints — while providing eternal barbecue anthems.

You can debate the original architect(s) of G-Funk, but on The Chronic Dre flipped Parliament-Funkadelic and all funk at his disposal into cinematic and mythic suites where squealing synths approximated beams of L.A. sunshine refracting off bouncing Impalas. The Chronic was so sonically tight that a then-young Snoop Dogg made the simple act of counting to four sound cool and subversive on “Nuthin’ But A ‘G’ Thang.” The gunshots and double-barrel-like drums on The Chronic rang out in neighborhoods — disenfranchised and wealthy alike — around the globe. G-funk dominated the majority of the ‘90s in the wake of The Chronic, strains of Dre’s signature interpolations permeating rap in Texas (e.g., ESG’s Ocean of Funk) and much of the South. In the mid-aughts, L.A.’s DJ Mustard pasted specs of Dre’s G-funk onto his minimalist “ratchet” sound, and the perfect squealing synths and woozy bass that Dre perfected still echo in the music of contemporary L.A. rap stars like G Perico and Drakeo the Ruler. The Chronic’s influence on rap is indelible, heard in the genre then, today, and forever. — Max Bell

1. Love — Forever Changes [Elektra, 1967]

In the summer of love, Arthur Lee was shrouded by premonitions of his impending demise. Barely 22, the frontman for L.A.’s definitive band foresaw people dropping dead from the window of his Laurel Canyon compound; the water in his bathtub oxidizing into blood; jangle pop leaking from long-shuttered clubs drowned out by wailing sirens. At the apex of Aquarian revolution, Arthur Lee threw an orchestral Last Supper, a celestial requiem for those damned but who didn’t know it yet. Over a half century later, Love’s Forever Changes remains the eternal soundtrack for the ephemeral city, a moonstruck Polaroid of psychedelic Los Angeles, masterminded by a South Central native originally from Memphis, a symphony of bleached sunshine and doomsday noir that could only exist at the crossroads of Clark and Hilldale.

1967. The impossible Kodachrome and flat-ironed myth. Here glows Arthur Lee, the eerie clairvoyant of the Sunset Strip, the reigning emperor in the wake of two stellar albums on Elektra and several hundred hallucinogenic ceremonies inside the Whiskey-A-Go-Go and the Brave New World. Lee, the acid priest with the baptized teardrop croon pulling up to Ben Frank’s (now Mel’s Drive-In) in a purple Porsche. The Dorsey dropout who graduated from teenage rhythm and blues prodigy to an oracular phantom in blue and red granny glasses, who taught Hendrix how to dress and for whom Jim Morrison might as well have built a shrine. After all, the Lizard King once said “if we could be as big as Love, my life would be complete.”

Even the band’s makeup felt ordained from a utopian L.A. archetype. The mystic Lee commanded the city’s first multi-racial rock band, a mercurial ex-star athlete from the heavily segregated blocks south of Pico. He was joined by lead guitarist Johnny Echols, a bent sorcerer on the six-string double neck Gibson, whose family had also headed west from North Memphis during the great migration. The other songwriter, Bryan MacLean, was a Beverly Hills-raised former Byrds roadie, a Brian Jones doppelganger with a celebrity architect father, who was reputed to have been Liza Minelli’s first kiss. MacLean replaced “Bummer Bobby” Beausoleil in an earlier incarnation of Love, leaving the latter to eventually commit murder for the Manson Family. The bassist, Ken Forssi, had recently left The Surfari’s, the one-hit Glendora wonders behind the quintessential surf rock anthem “Wipeout.”

Limited as a formal musician, Lee couldn’t play certain chords and lacked knowledge of music theory, so the songs had to be snatched from the starburst ether of his imagination. Enlisting an orchestrator (David Angel) and a 12-piece brass and string section, he turned acoustic reveries into baroque articles of faith. Stoned elegies became sacred liturgies, frail heartache melodies plinked on a Sunset Sound piano turned into stained glass cathedrals of harmony. All the right cameos exist: Forever Changes was co-produced by Bruce Botnick, the engineer of Pet Sounds and Let It Bleed, and producer of L.A. Woman; canonical session musicians The Wrecking Crew jam on two tracks, Neil Young reportedly helped arrange “The Daily Planet.” But these obsidian prophecies and afterlife psalms could only be summoned by Lee.

“I thought this might be the last album I’d ever make,” Lee once wrote about the creation of Forever Changes. “The words represented the last words I would say about this planet. I made it after I thought there was no hope left in the world.”

In a VVS falsetto, Lee croons revelations about the news of today becoming the movies of tomorrow, the fear of nuclear apocalypse, the unnamed villains seeking to lock him up and throw away the key — a grim harbinger of the legal troubles that eventually ensnared him. MacLean contributes “Old Man” and the record’s lone semi-hit “Alone Again Or,” a gorgeous flamenco ballad of sweet despair cleansed by a heaven-sent rain of mariachi horns. For all its ageless beauty, it couldn’t crack the Billboard Top 100; the album itself stalled at no. 154. Forever and now are two distinct ideas.

Shortly thereafter, the band dissolved, Vietnam intensified, the assassinations and riots of ’68 accelerated the descent, the election of Nixon and the Manson killings amplified the madness and paranoia and anger. But Lee saw it all first; Love were the originators and masters, who distilled the spirit but understood that tomorrow wasn’t promised, and even if it was, it might be worse. To absorb Forever Changes is to understand L.A itself: the transient beauty and the implicit threats of violence, the combustible dreams and the darkness lurking in every canyon, the fleeting potential for transcendence if the elements hit just right (and if you’re lucky), and the unshakeable sensation that when you open your eyes again it all might vanish. — Jeff Weiss