Riding the 70 bus from Boyle Heights to Downtown every day, I’d often see this one guy with a shock of unruly gray hair. Distinctive as much for his mane as for his swollen and bandaged legs, he’d shuffle on at the stop for LA County USC Medical Center and call dibs on the disabled seating. Beyond thinking, like, “Oh man, I hope that guy’s legs get better,” I didn’t pay him much attention. I didn’t think of him much at all. Until I saw him in a movie.

The movie was Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups. Christian Bale plays a brooding screenwriter who meanders aimlessly around L.A., sometimes pausing to ponder a homeless encampment. About halfway through the movie, the guy from my bus commute turns up opposite Cate Blanchett. She plays a doctor and he plays an ailing homeless man. In the seconds-long scene, she tends to his legs. He isn’t listed in the credits.

I always figured that I’d ask him about the cameo, but I never did. Eventually, I moved to a neighborhood serviced by different bus lines, quit my job, and made the decidedly ill-conceived career pivot to screenwriting. I set about meandering aimlessly through my newly unstructured life, albeit with less professional success than the Christian Bale character. Then, while visiting a friend on a Koreatown set one day, I see him again—the same guy, now in a wheelchair, hanging out across the street from the shoot.

“Holy smokes, that’s the guy,” I say.

“Ron Mitchell?”

“Wait, you know him?”

“Everyone knows Ron.”

It turned out everyone did know Ron Mitchell. When a photo of him accompanied an L.A. Times article about homeless presence on trains last April, commenters on Reddit spotted him immediately. “If you work in film and TV, you know him,” one wrote. “I heard stories that some of the top name directors actually stop production to go over and shake his hand and talk with him.”

For Wonder Woman director Patty Jenkins, Mitchell’s reputation preceded him. Jenkins noticed Mitchell hanging around the set of her upcoming series I Am the Night and learned from crew members that he’s a legendary film buff. He didn’t disappoint. “He is always filled with the most incredible stories and anecdotes about film history,” she wrote in an email. “He literally seems to know everything about the actual art of filmmaking.”

Director Dan Gilroy met Mitchell hanging out near the downtown L.A. set of Roman J. Israel Esq and the two would often have lunch together. Gilroy was immediately struck by Mitchell’s “vast knowledge of not only what is happening in the movie industry in the moment, but going way back,” he says. “We would have these long-ranging and far-reaching conversations.”

Mitchell, Gilroy points out, goes to great lengths in his commitment to a particular crew, often staying out for overnight shoots; He even turned up, inexplicably, at a Roman shoot in the desert near Lancaster. “Denzel, I think, got him a car back,” Gilroy recalls. “Everybody on the crew embraced him.” For his part, Gilroy laments the necessity of cutting of a scene featuring Mitchell from his latest project, the Netflix feature Velvet Buzzsaw, but he swears he’ll ensure Mitchell gets a cameo in his next L.A.-based project.

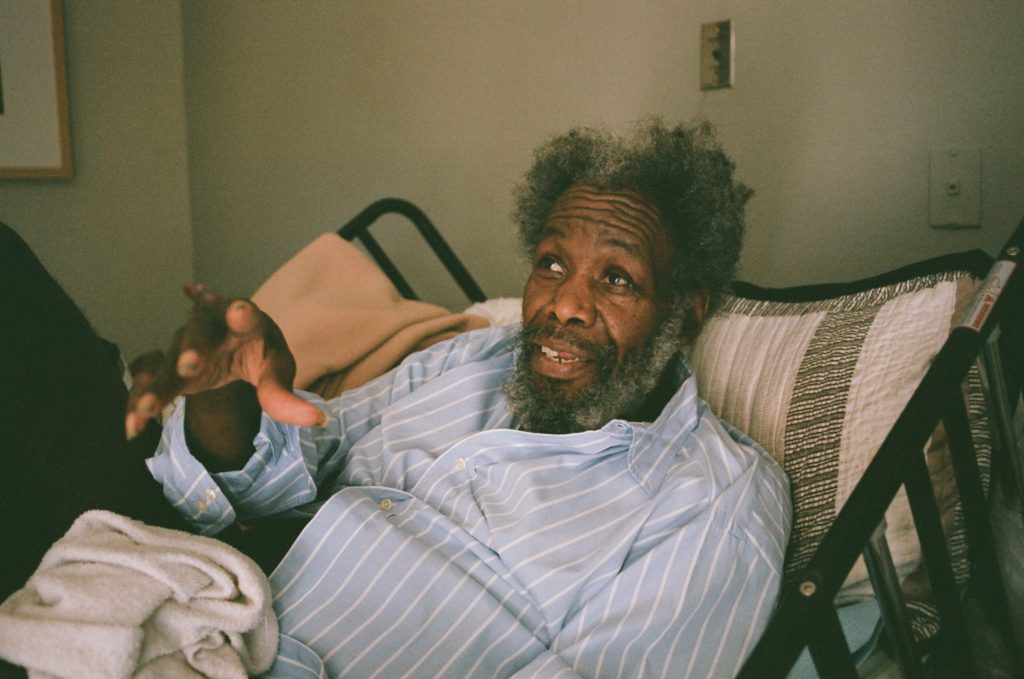

In July—three months after our chance encounter in Koreatown—I finally tracked down Ron Mitchell. I met him in the assisted living home where he now lives—bedridden, wearing only a towel, his belongings piled on three wheelchairs he’s somehow accumulated. “Assisted living is intense,” he tells me, as an alarm blares in the background. “But I find life here much more exciting than where I was a year ago.”

Here he goes by the name Ken Adam. It’s a made-up moniker he uses when interacting with medical personnel, social workers, and “government people,” as he calls them, as a way of distancing the real him from the guy who might as well be just another statistic.

For me, though, he’s just Ron.

Mitchell’s first brush with Hollywood came at the age of 17. It was 1967, and he’d traveled to California from Texas for a science fair, where he met a man who promised to connect him to some producer friends.

“He said if a movie ever came to Texas and he found out, he’d put me in touch with them,” Mitchell says. “People will say that, but he actually did it.” Sure enough, in 1970, Mitchell landed a job as a production assistant on Robert Altman’s Brewster McCloud.

After that, Mitchell drove a truck for Steven Spielberg’s The Sugarland Express and later worked as a production assistant on the likes of Paris, Texas; Goodfellas; and You’ve Got Mail. He describes himself as akin to Forrest Gump, and it’s a fitting comparison. He’s a kind-hearted presence who emerges in the background for moments of cinematic significance.

Mitchell has a penchant for name dropping, though he rarely seems conscious he’s doing it. He says Michael Bay — whom he worked with while playing a security guard in Transformers in 2007 — is intense as a director but extremely pleasant in person. Terrence Malick,who directed Mitchell in Knight of Cups, is “an actor’s dream,” Mitchell says. “In addition to being nurturing and encouraging, he offers a freedom that almost nobody trusts an actor with.”

Patty Jenkins

“He is always filled with the most incredible stories and anecdotes about film history… He literally seems to know everything about the actual art of filmmaking.”

Mitchell has been homeless for over 40 years. When work took him to New York, he’d continue traveling when the job was done, finding work where he could. “I’d sometimes spend nights on set,” he says. “I would spend a lot of nights writing. Kinkos used to be open 24 hours a day, so I’d go rent a computer, midnight till dawn.”

For a time in his 20s, he crashed at an informal art colony with a bevy of similarly-footloose peers in an abandoned home off La Brea. Renting a place of his own was an out-of-reach luxury. “I didn’t see a reason to spend that kind of money, and I didn’t have it most of the time,” he says. “Even if I’d had it, it wouldn’t have lasted forever.”

Last year, however, an upsetting series of events landed Mitchell in permanent housing. It all started with his legs. For decades, he’s battled a fungus that makes his feet swell as the skin cracks and scabs over. He kept the disease at bay until about ten years ago. Caring for his legs involved visits to a clinic where he showered and cleansed his infected skin, removing the fly larvae that would emerge after periods of exposure.

On his last visit in May, Mitchell was forced to leave the clinic before he could thoroughly wash his legs. In Union Station later, buying oatmeal from Starbucks, Ron drew the attention of an LAPD officer who noticed his condition and detained him on a 5150 hold—a provision that allows for the 72-hour confinement and psychiatric treatment of a person deemed incapable of providing their own food, clothing, or shelter due to a mental disorder. In Mitchell’s mind, this was an injustice.

“The cop is not a doctor,” he says. “People believe, ‘Well, he’s a cop, he must know something, we’d better tie this guy to a bed for three days.”

By the end of his confinement, Mitchell claims his legs had atrophied to the point that he could no longer stand.

Now he fears he’ll never regain his strength.

I call John Maceri, executive director of homeless services nonprofit The People Concern, to get another perspective on the 5150 process. Maceri, who has no knowledge of Mitchell’s situation, emphasizes the improbability that a 5150 hold would be abused. “I’m not aware of any circumstance where someone has been brought in on a 5150 hold inappropriately,” he says. “Usually, the intervention will do everything short of having to write a hold. It is essentially the last resort.” He does acknowledge, though, that 5150 holds can cause trauma and laments their unfortunate necessity.

Though many who are homeless and held for psychiatric evaluation are ultimately released back onto the street, Mitchell was transferred to assisted living at the end of last May. His placement is paid for by the county’s Housing for Health Division, which has been vastly expanded thanks to funds generated by Measure H, the sales tax ballot measure passed by LA County voters in 2017.

Ron Mitchell

“I’m not going to make a difference in anybody’s day. I’m just a guy you pass by eating pancakes in the Greyhound station. I came from nowhere, and I’m going nowhere. I would never be missed.”

The upshot is that Mitchell finally has a roof over his head, which makes him one less unhoused person—of the more than 30,000—on the streets of Los Angeles. But that doesn’t mean the experience hasn’t been demoralizing to him.

“This is an improvement, don’t get me wrong… But the county got this place for the person who’s here,” he says, explaining that the bed is designated for somebody — anybody. “That’s not the same thing as getting it for me.”

On the phone one day, Mitchell again returns to the Forrest Gump analogy, this time to dismiss it. “I’m not even as significant as Forrest Gump,” he says. “At least Forrest could run. Forrest was witty. I’m not going to make a difference in anybody’s day. I’m just a guy you pass by eating pancakes in the Greyhound station. I came from nowhere, and I’m going nowhere. I would never be missed.”

Yet, when I first visited, we were interrupted by a PA friend delivering a box of snacks. Mitchell took a call while I was there, and after hanging up, remarks: “You know the show Awkward? That was the producer. He wants to bring me a piano.”