On a nondescript corner in Lincoln Heights, sandwiched between World Nail and Spa and Escobar’s Travel Agency, is an unmarked door. Behind it lies a century old men’s club. Wood paneled, carpet lined and teeming with taxidermied polar bears, treasure chests, spears, shrunken heads, deep sea diving gear and an 85,000-year-old mastodon head, this is the home for the world’s foremost explorers, thrill seekers and planet roamers. This is the Los Angeles Adventurers’ Club.

Founded in 1922 by a group of men including Teddy Roosevelt, the club has seen over 1,000 members. Famous names include James Cameron, Buzz Aldrin and Cecil B. DeMille. Alongside lesser known adventurers, they have earned memberships doing some of the most extraordinary, insane and frankly bizarre missions imaginable. There’s the competitive tandem surfer who hitchhiked a flight to Kathmandu with the then Prime Minister of Nepal. Then there’s the man who sailed across the Atlantic with his dog, but crashed the boat and paid his way home by playing clarinet on street corners. Members are scientists, physicists, anthropologists, doctors, engineers and artists. Membership is invitation only. Meetings are every Thursday in the organization’s longtime clubhouse, rented from freemasons. Business attire is required. Only men are allowed.

This is a major point of contention for the Adventurers’ Club. Though it has persisted for nearly a century, it has arrived at a juncture, with tensions mounting between members who insist on tradition and others who want to rewrite the rule book. There are those who feel the biggest risk to the club is male ego, and others who would shred their membership cards were women to be invited. Up to several times a month, however, the club offers “Ladies Nights,” which are intended to accommodate wives and friends of members. Though I am neither a wife nor a friend of a club member, I’d caught wind of the club through word of mouth, and in the spirit of adventure, I decide to attend a “Ladies Self Defense Night.”

On a Thursday in September, I am greeted at the door by an 80-year-old pilot who tells me he survived a mid-air collision. “Dr. Bernie Redman, 1063,” he says. At the club, it is tradition for members to introduce themselves with their name, followed by their member number.

The Adventurers’ Club has no social media presence. It doesn’t advertise, and it doesn’t do outreach. There is a rudimentary website designed by skindiver Stewart Deats, #1168. And the interior of the clubhouse itself feels notably untapped by anyone seeking to modernize or commercialize it. The space resembles an old museum or a preserved historic site. There are wooden chairs, tungsten bulbs in brass fixtures and glass cases containing yellowed letters, frayed books and chipped ceramics dating back hundreds of years.

The Adventurers themselves, most of whom are above the age of 60, contribute to the feeling of having entered a time capsule. As Redman walks me through the club’s halls, men with bushy mustaches—many with gold rings, some in cowboy boots—socialize with women with coiffed hair and long dresses. It feels like courtship 101 from the early 20th Century, with men recounting harrowing and heroic tales to female listeners. It is grossly old fashioned, but to the men’s credit, their stories are an unusual sort of fascinating. They are the kind of stories that warrant telling.

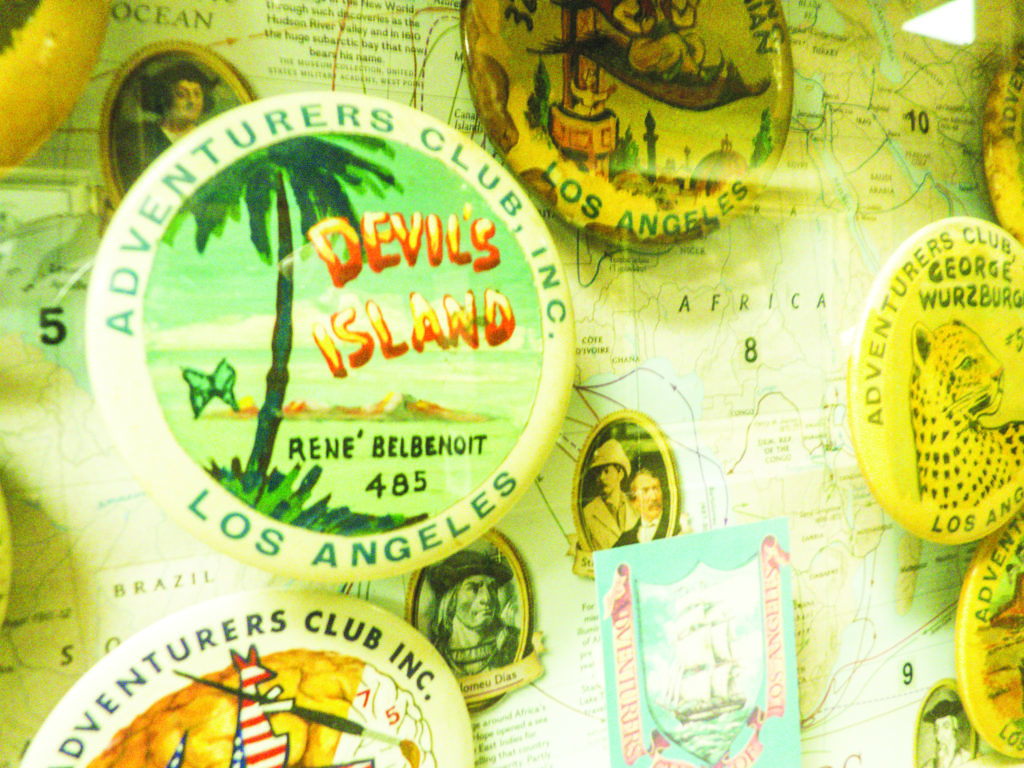

Redman shows me the vestibule lined with members’ photos and personalized buttons. It leads to a long room with taxidermied animals—Pythons, a 9-foot swordfish, black rhinos, rams, and lions—hanging from every inch of the walls. “We’ve got some bears too,” Redman says. “But, these are from years ago. Today we shoot animals with cameras.”

He points to a list hanging on the wall, penned by John Goddard, #507, an explorer and anthropologist dubbed “the real Indiana Jones.” Among the checked-off items: “Climb Mt Vesuvius,” “Ride Horse in Rose Parade,” “play Clair de Lune on the piano,” become proficient in the use of a plane, motorcycle, tractor, surfboard, rifle, pistol, canoe, microscope, football, basketball, bow and arrow, lariat and boomerang,” Unchecked items include: “Appear in a Tarzan movie,” and “Own a horse, chimpanzee, cheetah, ocelot and coyote.”

As I shake hands with adventurer after adventurer, I feel there’s an excitement that I’m a visitor, and that it’s my first time in the club. “You find a warmth, and a closeness here,” says Joe Valecic, #1107, who says he developed one of the first underwater color video systems used for wildlife TV programs. “If somebody’s going on an expedition and needs an underwater camera, well they can call me and get it for free. Likewise, if I need climbing aids or climbing boots, oh, just call Larry. He’ll get you whatever you want.”

As the story goes, when the adventurers gathered for their first meeting in 1922, four toasts were offered: “To Adventure, the Shadow of Every Red-Blooded Man,” “To the Game,” “To Every Lost Trail, Lost Cause and Lost Comrade,” and lastly, “To Gentlemen Adventurers.”

As Redman and I continue through the clubhouse, I realize it’s not the weapons, expedition flags or hunting trophies that make the club feel masculine—it’s the collection of pin-up-style photos of naked women carefully tucked away behind the pull-down “The Ladies Night” banner that remind me women have no footprint here.

The exclusion of women is the most glaring difference between the Adventurers’ Club and other organizations for adventurers around the world. The biggest and most reputable is the Explorers’ Club, headquartered in a townhouse off Central Park in New York City. It became coed in 1981. The Adventurers’ Club has voted twice, once in 1995 and again in 2014, to allow women entry into the club. Both times, the outcome was “no.”

But it’s not as though the club is opposed to breaking from tradition. The trove of rhino heads, polar bears and other stuffed animals, for example, are now regarded as uncouth and hunting is no longer an acceptable form of adventure. What’s more, plenty of the strict membership rules have fallen by the wayside. It used to be that you had to attend club meetings for a year before you were invited to join. Dinners were mandatory; they were viewed as essential to maintain the bond of community, and also as treasured occasions to get to know and to learn from fellow adventurers. The process for membership has since been shortened to as little as a few months. Dinners are now optional.

If the rules on membership have been loosened over the years, why hasn’t the ban on women?

Redman rings the brass dinner bell. “Cover your ears, please!” he yells.

As we line up with paper plates for meatloaf, made by a chef whose family has been cooking for the adventurers for more than 30 years, I ask why the club has always voted to remain single-sex. The most common answer is a shrug that seems to imply, well, it’s tradition.

“The club was founded when gentlemen’s clubs were common,” says Valecic, the videographer who built his own 52-foot boat, dubbed the research vessel quest. (It was docked for years, he says, next to John Wayne’s in Newport Beach.) “This was back in the early 20th Century, when members liked the time to discuss things other than probably what their wives would want to discuss at dinner,” Valecic says. “It’s a place for guys to have camaraderie and get together.”

As we eat, the men ask me about myself, about my line of work and my own adventures. I had assumed that because I am a woman and therefore have no potential as a club member, the adventurers wouldn’t be interested in what I had to say. But they listen; they ask questions. I’m pleasantly surprised.

When I express my own conflicted feelings about a club that excludes women—who are still egregiously underrepresented in many professions—Wayne White, #1194 assures me that the point of a men’s club is not to send the message that women are unequal, but to offer men a place to be with other men. “I personally think men are in a bit of a crisis right now. There’s enough things going on in society and with certain groups trying to break down spaces for men,” he says. The way he sees it, the club is facing societal pressure to “do the right thing” and admit women. The harder task in today’s climate, he argues, would be to fight for the rare opportunity to maintain a men’s only space.

“I personally think men are in a bit of a crisis right now. There’s enough things going on in society and with certain groups trying to break down spaces for men”

Wayne White, #1194

There are a handful of things I would like to say in response to this, but Kevin Lee, a scuba diver who has searched for sea slugs on all seven continents, chimes in. “We can let our hair down on men’s only nights and use different language than we would when ladies are present,” Lee says. “The dynamic would change. The meetings would feel different.”

I speak with Casey Shepard, a woman who’s traveled the world by van and bike. She spoke about her travels during a meeting several years ago and still visits the club from time to time. “When I mentioned I was married,” she tells me, “One man said, ‘If I were her husband, I wouldn’t trust my wife being gone that long.’”

According to anthropologist and fine-arts teacher Pierre Odier, 988, comments about women’s appearances are not infrequent at the Adventurers’ Club. And he resents that Ladies’ Nights (which have since been listed on the club’s website as “Open Nights”) often turn into date nights, platforms for men to brag and seduce or simply show off the women they’ve invited.

Bob Oberto, a pilot, aerospace engineer and NASA-trained research scuba diver, says he finds the club’s ban on women embarrassing. “It was a handful of female friends who introduced me to the club, and they are not allowed to be members,” he says. I rationalize it and think, ‘Well, the club is so old. It’s almost kind of kitschy that you’d have a bunch of old guys hanging onto an old men’s club from the Empire, British Empire days. But in reality, women are quite bothered by it.”

Andrea Donnellan, a geophysicist and principal research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, discovered the club in the early 2000’s and was a regular attendee and speaker at Ladies Nights for years. While she said never felt disrespected during those events, she held out hope that the club would someday become co-ed, as many members had promised her early on. But when the adventurers voted down the option to admit women in 2014, Donnellan felt profoundly let down. One night following the vote, she accidentally showed up to a men’s only meeting. She was turned away at the door and never came back.

Shepard admits she feels torn about returning to the club. “It is a hidden gem, an amazing, epic place,” she says. “But at the same time, I am an adventurer. I go to the organization to learn and to talk about adventure. And the club members make it about gender. I think they have to decide: Is it a men’s club, or is it an adventurers’ club?”

After dessert, Redman rings the bell again, announcing the end of dinner and the start of the meeting. We stack our plates and file into the great hall.

The first order of business is to rise for a moment of silence for those who have disappeared and remain missing on adventure. This happens from time to time. There are the men who went missing while whale-watching in Baja, and the 61-year-old insurance salesman who set out on a 10,000-mile sailing expedition in 2003 and never came home. We also take time to acknowledge those who have euphemistically “gone on the great adventure.”

“These days, unfortunately, there are deaths,” says Vince Weatherby, #1060. “Our club is nearly 100 years old. And many of the founding members are passing away.”

The club is ushering in a new generation of adventures, but few of them have any intention of rewriting the rules.

Alec Shumate is in his early 30s and makes his living as a storyboard artist. But here at the Adventurers’ Club, he identifies as an “expedition artist” and says he’s planning a trip to sketch wildlife in the Amazon. He was recently voted to serve on the board of the Adventurers’ Club, a place he says is empowering, in part, because of its all-male membership. “There is something special, at least for me personally, about that kind of camaraderie and the mentorship that I can find in an all-male institution,” Shumate says. “When I come into the club, I feel one step closer to being the kind of person that I want to be one day.”

In the great hall, a woman named Linda Abrams, who looks to be in her 70s, shares plans for her next adventure. “I’m flying my 415-C to the Mojave desert to for the Ercoupe Convention in a few weeks,” Abrams says, revealing herself to be not a wife or a friend of the club, but a adventurer in her own right.

A male adventurer stands. “I lost my wallet going through security,” he says. The crowd chuckles.

Abrams smiles politely. I fight an eye roll.

During the women’s self defense training, a frail, slightly hunched man who is revealed to be 96 years old takes the stage. His name is Sid Hallburn, #998. Halburn served in the Office of Strategic Services, a precursor to the CIA, during World War II. He was a Grand Mixed Martial Arts Master and a professional tap dancer who trained with Gene Kelly, Shirley Temple and Judy Garland. I find these facts delightful, and Hallburn himself even more so. “I’ve seen a lot in my life,” he insists, “But I’m nothing special.”

Hallburn begins his tutorial by listing the three “Categories of People Who Are Going to Hurt You.” The first is teenagers. “They don’t want to rape you,” Hallburn said. “They just want your money.” The next type is “Mr. Know it All.” He’s really slick and really smooth,” Halburn says. “He’s a family member or a friend. And he wants to rape or molest you. But he’s not interested in killing you.” And the final group: “The guy who wants to rape you and take you to the desert somewhere and dump your body.”

Hallburn then brings up an assistant named Fred Culkowski, a 60-something longtime Filipino weapons expert. Culkowski distributes copies of a list, handwritten by Halburn. “Things To Help You If Needed,” it reads. Those include things like “Saw,” “Hammer,” “Hot Coffee” “Chair and other furniture,” “Knife (Butcher), keep one in purse.”

At the bottom is a note: “Our Video is only $14.95 we pay the shipping its not another martial arts video–we also have a secret weapon that can stop anyone in seconds.”

Hallburn then demonstrates how to use each of the objects named on the list. “Come at me,” he says to Culkowski. The adventurers and I watch as Hallburn fends off his assistant with a hammer; a Campbell’s soup can; then an ice pick. “Eyes, stomach, side of the head, between the legs and side of the head again. That’ll stop him.”

Not unlike everything else I have experienced at the club, there is something amazing and completely baffling about this demonstration. I look around the room at the men nodding, taking in this lesson from a 96-year-old about warding off rapists with butchers’ knives. Initially, I am amused by Hallburn and his quirky biography. But then I am unsettled. I feel growing discomfort watching a program that men have curated on my behalf, which they have deemed helpful for my safety. I can appreciate that the club was founded in another era, and that views on gender used to be different. But looking around the Adventurers’ Club, I see men using the club’s history as an excuse to live in the past, embracing outdated ideas about gender and power.

But looking around the Adventurers’ Club, I see men using the club’s history as an excuse to live in the past, embracing outdated ideas about gender and power.

Hallburn pulls out a pistol and gestures towards the audience. “You probably don’t want to kill him, so shoot him in the leg,” he says. “That’ll stop him.”

During the Q&A, a woman raises her hand and asks about the “not another martial arts video” advertised at the bottom of the handout for $14.95. Hallburn says he has no idea what she’s talking about.

Following a round of applause for the conclusion of the meeting, I approach Abrams, curious to learn more about her. She tells me about her upcoming solo flight to a spaceport in Las Cruces, New Mexico, and about the Renaissance reenactment club she devotes herself to when she’s not climbing aboard her vintage two-seater plane. I ask if she wishes the club allowed women.

“Not at all,” she says. “I like it as is.” She must read the surprise on my face, because her tone becomes stern. “Now, the word counterculture used to mean something different, but I’m going to be literal in the way I’m using it here … I am counter to the present cultural trend that tries to homogenize men and women,” she says. “I enjoy men being men, and I have no problem at all with a club that specifies that it’s for men.”

After the meeting, many of the adventurers shake my hand and tell me to please come back, but I’m not so sure I can endure another male lecture.

“We have another Ladies Night next week,” Weatherby says. “It’s a man who documented Russian teen royalty kidnapped in the Amazon!”

I have to admit, begrudgingly, that I am intrigued.