Built in 1939 in the Hollywood Regency style,

the Selma Las Palmas Courtyard Apartments in Hollywood boasts 80 units, each one slightly different from the next. The moulding, tiling and decorative woodwork vary from one unit to the next, though most still have tall multi-paned windows and antique doorknobs. Well-cared for common spaces define the complex: two central gardens and wide, decoratively-tiled entryways opening onto Las Palmas. The gardens encourage a kind of community that has, over the decades, become harder to find in a major metropolis like Los Angeles.

Developer Ben Weingart intended the courtyard apartments to house the working-and-middle class employees of the nearby movie studios — most notably, the former Columbia Studios lot at Sunset and Gower. The building, in fact, dates back to a time that now inspires nostalgia — when architects, planners and developers strove to create housing for working urban families that was not only affordable, but also beautiful and desirable.

Though Weingart sold most of his properties soon after developing them, he held onto the courtyard apartments, along with several Skid Row hotels he’d converted into low-income apartments, until his death in 1980. They were personally significant for the developer, who considered himself civically-minded and saw these buildings as contributing to his vision for quality lower-income living in the city. His family eventually sold the properties. Today, more than half of the rental units at the Selma Las Palmas Courtyard Apartments sit vacant, the result of a state law that allows landlords to evict tenants from rent-controlled units in exchange for a small relocation fee, typically when those buildings are facing demolition for redevelopment.

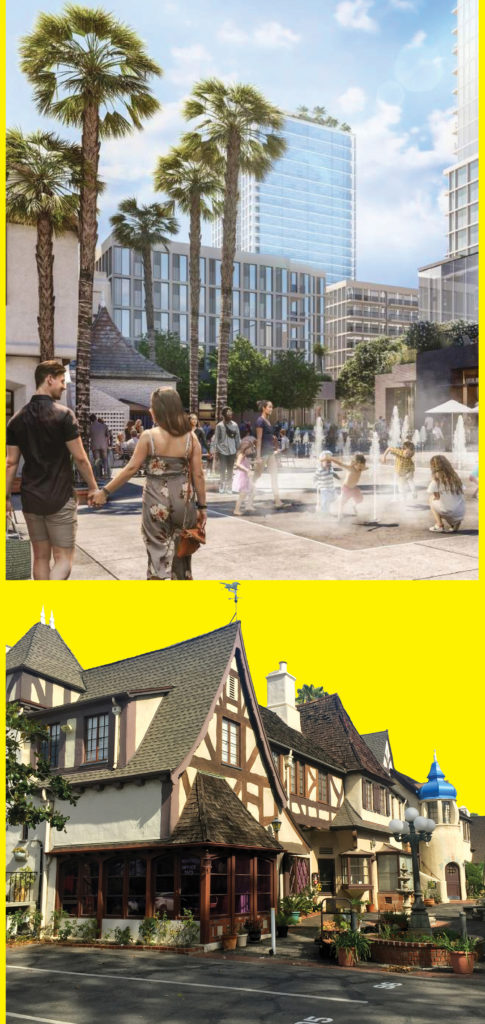

After the courtyard apartments are demolished, a mixed-use, contentious luxury development featuring multiple glass skyscrapers will soon rise in their place. The 1.4 million-square-foot project, called Crossroads Hollywood, is slated to include a 308-room hotel, 190,000-square-feet of retail, restaurants and office space, and 950 luxury apartments. It will also have at least 105 affordable housing units — for which the city offers financial incentives to developers — and potentially more, depending on the outcome of negotiations with displaced tenants, as a concession for the 82 rent-stabilized units the project will destroy.

Three Selma Las Palmas tenants have sued the project’s developer, Harridge Development Group, along with real estate developer Morton La Kretz, who bought the adored, nautical-style office complex, Crossroads of the World, in 1977. He acquired many of the surrounding properties in the 1990s. (La Kretz is now in his 90s, and his daughter, Linda Duttenhaver, runs his development company.) The tenants are waiting to see whether they will be able to live in the new development that replaces their homes, and the Crossroads Tenants Association, formed by tenants of the building, has also filed a separate complaint against the developer, alleging defamation and duress.

On the surface, the Crossroads Hollywood project is not unlike other behemoth mixed-use developments gaining approval left and right throughout the city. But the destruction it threatens to leave in its wake is particularly dramatic, considering that three out of the five buildings it will either demolish or relocate to appease preservationists have been deemed historically significant. One of the few buildings that will be preserved is the circa-1931 complex from which this new development takes its name: the Crossroads of the World, a quaint office and retail plaza often described as the nation’s first outdoor shopping mall (though in fact, the Mercantil Arcade in downtown L.A. opened earlier). Famously, it is topped with a red and blue globe that looms over the central building, with its charming blue awning, like a scaled-down space needle.

This beloved plaza will become the token centerpiece for the multiple glass skyscrapers that will surround it on all sides. But many of the nearby buildings will not survive. Between 2017 and 2018, The Cultural Heritage Commission —comprised of architects and preservationists appointed by Mayor Eric Garcetti — recommended five of the buildings in the footprint of Crossroads Hollywood for Historic-Cultural Monument status: the Hollywood Reporter building, the Talbot-Woods craftsman-style duplex, one pristinely-maintained 1910 bungalow, the Selma-Las Palmas courtyard apartments, and the 1920s Bullinger Building, (though the developers are still considering incorporating aspects of the Bullinger.)

In their overlapping fights for affordable housing and historic preservation, otherwise disparate activists have turned to the Historic Cultural Monument nomination process as a last resort for preserving infrastructure, and therefore, housing. This form of coveted city status earmarks a building as historically or culturally significant. But more than that, it has also become weaponized as a political tool for slowing down and even halting demolition. There’s one big hurdle, however: Once the commission recommends a building, the nomination goes before the City Council’s Planning and Land Use Management (PLUM) committee, which makes the final call.

In November 2017, the PLUM committee decided to grant landmark status to the circa-1937 Hollywood Reporter building (also the one-time home of LA Weekly), which will be incorporated into the new development as a result. But nearly a year later, at an August 2018 hearing, the four other nominated buildings were denied landmark status, with the PLUM committee taking a dismissive, perfunctory attitude that surprised even preservation veterans. For example, in presenting the 1910 Major Kunkel Bungalow, principal city planner Ken Bernstein explained that its original owner had served as the first air pollution controller for the city, and later spearheaded efforts to measure and control air pollution of automobiles. Other cities in the United States and Canada sought his guidance as they developed their own anti-pollution policies. “Yeah, I’ve never heard of Major Kunkel before,” said councilmember Bob Blumenfield. “I mean, everyone’s part of history.” Bernstein explained again about air pollution and the problem of smog in Los Angeles, but Huizar quickly moved to deny the nomination.

Just three months after the contested Crossroads hearing, Councilmember Jose Huizar resigned as longtime chair of the Planning and Land Use Management Committee (PLUM) amid an ongoing FBI investigation into his dealing with developers. He is alleged to have accepted at least $1.5 million in bribes from developers in exchange for approving their projects. In late June, he was arrested on federal racketeering charges and removed from the city payroll. With this added layer of corruption and obfuscation, the story of the Crossroads Hollywood project — which is at the center of a battle over affordable housing, historical preservation, and luxury development — becomes as sinister and disconcerting as an L.A. noir.

To historians and preservationists,

the historic value of the original properties surrounding Crossroads of the World is clear. Richard Adkins, collections manager at and former president of the Hollywood Heritage Museum, calls the properties “endangered stock.” He points out that the craftsman bungalows and the duplex in the project’s footprint were built in the 1910s, around the time the city of Los Angeles annexed what was then the separate city of Hollywood. He also notes that PLUM frequently fails to approve the Cultural Heritage Commission’s recommendations, even though the commission was established in 1962 to curb the city’s ongoing habit of knocking down its own history. “The great concern is that the work of one city agency is being undermined by another,” Adkins says.

But seeking Historic-Cultural Monument status isn’t always about preserving history alone. Increasingly, the Cultural Heritage Commission hears from people who are seeking Historic Cultural Status for yet another reason: They fear losing their homes to new development. “It’s clearly about the preservation of the housing as much as about the preservation of the historic resource,” observes architect Gail Kennard, a member of the Commission who voted to preserve the buildings threatened by the Crossroads Hollywood Project. “I’m not against the growth. But how can we do it in a way that is less disruptive to people of middle and lower income? That’s the question that we’ve got to grapple with.”

It’s clearly about the preservation of the housing as much as about the preservation of the historic resource

Gail Kennard

Miki Jackson, an affordable housing advocate and consultant for the Aids Healthcare Foundation, which has a reputation for attempting to use historic preservation and adversarial litigation to prevent new development, puts it more bluntly. “The historic buildings issue has been there for a long time. The housing crisis is newer,” she says. “I advocate building truly affordable housing. I do not believe that luxury apartments do anything but hurt the working class.”

The number of buildings threatened by development has soared over the last two decades, making the Historic Cultural Nomination process both more urgent and more uncertain. Margot Gerber, president of the Art Deco Society, which helped fight to preserve two of the buildings in the path of the Crossroads development, recalls how much simpler the historic nomination process was in the 1980s and 1990s. “Because there was so much land for so long in Los Angeles, people would say, ‘Okay, you want to nominate that building,’” she says, explaining that monument status was usually granted. “Nobody cared.”

Historian Anna Marie Brooks has watched the process become increasingly hostile. “It’s just pure hell now,” she says. She recalls Councilmember Ed P. Reyes, who chaired PLUM until 2013, as being slightly more receptive to approving these landmarks: “At least you felt you had half a chance.” But Huizar, the chair from 2013 to 2018, “wouldn’t allow anything through,” she says.

Huizar’s ascent to the helm of PLUM coincided with both an increase in the number of HCM nominations and a decrease in the percentage of those nominations actually approved. From 2010-2012, the commission received an average of 24 applications annually, with 72 percent of applications approved in 2012. But during Huizar’s five-year tenure, the commission received an average of 37 applications per year, approximately 67 percent of which were eventually approved. A boom in development during this same period made the rejections feel all the more acute.

More significantly, the nominations PLUM has rejected in recent years have been disproportionately tied to new development or redevelopment projects. For instance, eight of the ten nominations dismissed in 2018 were undergoing extensive renovation or endangered by planned developments. Huizar also allegedly had back room meetings with a number of developers with interests in altering or demolishing historic buildings during his time in office.

The historic buildings issue has been there for a long time. The housing crisis is newer.

Miki Jackson

The councilmember’s entanglements with developers have long cast a shadow over his leadership. On October 22, 2018, Mayra Alvarez, a former employee of Huizar, sued the councilmember for harassment, retaliation, and discrimination. Her complaint claimed that Huizar frequently asked her to alter his official calendar — which is public record — to omit his meetings with developers and lobbyists, especially if their projects or concerns were soon to come before PLUM.

Huizar called Alvarez’s claims “nonsense,” though subsequent wrongful termination suits filed against him by other former staffers suggest a similar pattern of inappropriate donations and attempts to extort money of solicit bribes.

But far more damning allegations against Huizar started emerging when the FBI began making its own indictments in spring 2020. First came federal charges against political fundraiser Justin Jangwoo Kim, who allegedly negotiated $300,000 in bribes for Huizar. Then, George Esparza, a former Huizar aid, agreed to plead guilty for allegedly helping Huizar extort money from developers planning projects in L.A. — directing much of these funds to a political action committee set up to help Huizar’s wife, Richelle Huizar, win his seat once he was termed out.

While Huizar stepped down from all committees after FBI agents raided his home and office in November 2018, he did not resign. His colleagues waited until he was arrested over a year-and-a-half later, in late June of this year, before they voted to eject him from the council. The DOJ dropped a 116-page affidavit, complete with a two-page table of contents and photographs of illicit money stuffed in boxes and various crevices — like the Australian currency spilling out of a car’s central console, while a print-out Huizar’s councilmember schedule is propped behind the gear shift. The currency came from cashed-out casino chips, given to Huizar by a real estate developer who financed the trip to Australia and other trips to Vegas casinos. The same developer, who also helped the councilmember secure $570,000 to settle a sexual harassment suit, received a litany of favors in return, most importantly clearing the way for a 77-story downtown tower.

“Developers would like to be able to have no rules whatsoever and to be able to simply pick and choose from plots of land that they can get large amounts of money to build on”

Richard Schave

Councilmember Herb Wesson, who described Huizar as “like my brother, my best friend on the council” when Huizar faced a sexual harassment suit in 2013, took over as PLUM’s chair after Huizar’s resignation. But he too has been implicated in development-related scandals.

A search warrant filed by FBI agents in late 2018 sought information related to bribery and extortion between City Council staff and businesspersons involved in the redevelopment of the Luxe Hotel downtown. Located next to the Staples Center, the Luxe hosted campaign events for multiple local politicians including councilmembers Herb Wesson and Monica Rodriguez. When the LA Times asked Wesson and Rodriguez why they had not paid Luxe for hosting these events, both demurred, saying they simply never received invoices. City Council committees had reviewed proposals and applications from the Luxe’s new owner in 2015, 2017, and 2018.

Preservationist Richard Schave has been tracking City Hall’s alleged corruption for years alongside his collaborator and wife, L.A. chronicler Kim Cooper, and no longer finds such dealings surprising. “Developers would like to be able to have no rules whatsoever and to be able to simply pick and choose from plots of land that they can get large amounts of money to build on,” Schave says. “I’m an incredibly positive person, but it’s really a cold cup of coffee,” he added, referring to the demolitions planned for Crossroads Hollywood. He and Cooper, who run the historically-savvy sightseeing company Esotouric, have long been planning a Jose Huizar bus tour featuring sites affected by the councilmember’s alleged corruption, waiting to launch it until Huizar was indicted. Even if Crossroads Hollywood isn’t on it, similarly disputed developments will be.

The effects of the new Crossroads Hollywood development

have already been felt most acutely by the tenants of the Selma-Las Palmas Courtyard Apartments. A small group of residents who appeared in front of the PLUM committee during the nomination hearing in 2018 each argued that the courtyard fostered community in ways the new development never could. “It’s just something that gives you peace of mind,” said Aura Valenzuela, who lived there with her mother and small daughter, referring to the shared central garden. Kevin Atteberry, a resident for nearly two decades, noted that, in contrast to the courtyard apartments, “Today’s apartment design is very isolating.”

The residents, who had formed their own tenants association a year before the hearing, continued to meet regularly after the failed HCM proposal, appearing at City Council meetings and participating in protests and press conferences sponsored by the L.A. Tenants Union and Coalition to Preserve L.A., voicing their opposition to the development. But in January 2019, once the Crossroads Hollywood project received the final City Council approvals it needed to move forward, the tenants’ priorities shifted, from resistance to negotiation. They wanted to ensure that they not only had suitable buyout deals — early on, Harridge allegedly offered discounted rent to tenants, which amounted to less than the minimum they should have been offered under the Ellis Act — but also a right to return once the new development was complete.

Around the same time, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation filed a lawsuit against the city. In it, they alleged the City Council had approved an Environmental Impact Report for Crossroads Hollywood that did not adequately address the project’s probable effect on the traffic, air quality and neighborhood residents. The tactic backfired, at least in the eyes of some tenants, who felt they were making headway negotiating for temporary relocation during construction and a 36-month payout. They say the lawsuit further strained their negotiations with Harridge.

During the AHF lawsuit, Harridge threatened to withdraw from negotiations, then after the AHF complaint was dismissed, the company told tenants that they would cease negotiations, discarding many previously agreed-upon protections and only offering Ellis Act evictions and a right of return. (When the city approved the Crossroads project, it mandated that displaced tenants be offered a “right of first refusal” to units in the new building, priced no higher than their current rent.) “We feel like we’ve been used as pawns between AHF and the developer,” says tenant Darrin Wilstead, a leader of the Crossroads Tenants Association.

On August 29, 2019, Harridge representatives met with the Crossroads Tenants Association, offering them chicken sandwiches and tamales before explaining the new terms of the Ellis Act eviction notices tenants had already received. As Bill Meyers, a member of Harridge’s development team, explained, tenants would have 120 days to vacate, though this could be extended to 240 days for the elderly, disabled or tenants with children; they would receive at least $11,125. They would also soon receive a “right to return” agreement, allowing rent-controlled tenants to move into the new development at their current rate, which they would need to sign and return within 45 days.

When these agreements arrived, they were far less flexible than tenants had hoped. Among other stipulations, the agreements specified that the “owner may abandon the Crossroads Project” at any time, thus terminating any promises to tenants, and that tenants who signed would not be allowed to disparage the property owner, or “sue, challenge, or contest, administratively, judicially, or publicly.” They also had to agree not to provide any “direct or indirect” cooperation to any other individual suing, challenging or contesting the project.

This felt like a gag order to many tenants. Jaime Sanchez, a resident of the building, sent the agreement back with multiple conditions crossed out and a letter attached. “When a successful Plan for First Right of Refusal has been crafted along with the tenants, then I will consider the condition fulfilled,” he wrote. Two other tenants, Daniel Hernandez and Rosemary Fajarait, also objected to the agreement, but sent letters to Harridge stating their intent to return to the new development. Neither Hernandez nor Farjarait heard back.

Last December, the Los Angeles Tenants Union Hollywood Local filed a lawsuit against Harridge with Sanchez, Hernandez and Fajarait as co-plaintiffs. It alleged not only that the developer violated city conditions, but that it acted negligently and unlawfully in pressuring tenants to move out before ensuring they knew what protections and compensation they were entitled to under the Los Angeles Municipal Code and Los Angeles Rent Stabilization Ordinance.

In the union’s five-year history, this was the first time they’d ever filed a suit against a developer. “Typically the threat of the union suing was enough,” explains Susan Hunter, the union case worker assisting the Crossroads tenants. She sees the suit as a way to “acknowledge that we can’t keep displacing tenants from rent controlled housing in order to build luxury housing that the majority of workers in this city can’t afford.”

Harridge’s law firm, DLA Piper, responded by arguing that in fact, the Right to Return agreement had been approved by City Council District 13, Mitch O’Farrell’s district, and thus the lawsuit was unfounded. In March of this year, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Barbara M. Scheper dismissed the case, on the grounds that the plaintiffs needed to sue the city instead of the developer.

The plaintiffs filed their motion to appeal in late March, just days before the Crossroads Tenants Association submitted their own complaint against the developer to L.A.’s Superior Court. Their allegations include defamation (last year, a representative of Harridge told the L.A. Times that tenants had been trying to sell their right to return, a claim tenants deny), duress, and an unconscionable contract. They are not sure if anything will come of the lawsuit, but they wanted their experience on public record.

All this occurred amidst a surreal landscape: a shelter at home ordinance was in place in an effort to quell the spread of COVID-19, unemployment was ballooning, the tenant’s union was pushing City Council members for greater renter protections as new details from the FBI’s probe into City Hall corruption dropped almost weekly.

For now, the nearly 40 families who still live in the courtyard are waiting to see whether the virus will affect their August move out date, and, once they leave, whether they’ll ever return to the place that once formed the nexus of their community. “We all think it’s a nice idea to be able to come back, but there are some doubts, such as about whether the project will ever be completed,” says Wilstead. “At the end of the day, looking for a new home amidst a pandemic and a financial crisis is daunting.”

This article appears in Vol. 2, Issue 2 of The LAnd. Click here to pre-order your copy.